Feature | Black Lives Need to Matter: Examining the Inequalities Within Medicine

Every year, tens of thousands of medical students across the U.S. pledge to uphold the highest pillars of ethical responsibility as they embark on the journey of becoming a physician.

Historically, this charge was embodied by the Hippocratic oath, attributed to the Father of Medicine, Hippocrates, who was the first to investigate the organic nature of disease.

Two thousand years later, the role of the modern-day physician has evolved to not only treating the organic causes of disease but also investigating the societal contributors to poor health.

Although the vows taken by the newest generation of medical trainees reflect this call to arms, there remains relatively little progress in improving health care disparities in vulnerable populations, particularly in the African American community.

One need only look at the events of last month to appreciate the inequalities faced by African Americans.

As demonstrated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and protests inspired by George Floyd, two sentinel events that may come to define the future of public health and law enforcement policy, African Americans have been disproportionately victimized.

In Chicago, African Americans have been found to represent more than half of COVID-19 cases and nearly 70% of case fatalities, despite comprising only 30% of the city population. This epidemiologic observation has been confirmed in numerous other cities and states.1

In the U.S., African Americans experience an incarceration rate that is five-times higher than white Americans and they are three-times more likely to be killed by police compared with white Americans, despite comprising less than 15% of the population.2,3

While the overlapping occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the George Floyd protests may have been purely coincidental, there is a similar set of underlying inequalities in medicine and law that we must seek to identify and reform.

In considering the compelling factors behind the crisis facing our nation today, we must consciously examine the parallels within medicine that have led to the pervasive inequality in the care of African Americans.

While it is understood that cardiovascular disease is the leading killer of all Americans, African Americans experience disproportionately higher rates of mortality from conditions we as cardiologists have been tasked to treat, including coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes and hypertension.

Similar parallels can be drawn between the factors underlying poor outcomes for African Americans in cardiovascular disease and in law enforcement: including underlying mistrust of the institutional framework, the socioeconomic barriers that limit their access to essential resources, and the inertia from the relevant providers and professional societies in resolving these persisting disparities.

Mistrust of the Health Care Institution

As is true in law enforcement, trust is of extreme importance in the development, maintenance and overall effectiveness of the patient-physician relationship.

When this trust is broken, it becomes increasingly difficult to deliver appropriate health care due to a combination of poor patient satisfaction, lack of outpatient follow-up, and noncompliance with treatments.

One incident left a particular deep scar on the African American community's ability to trust the medical community: the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis, in which the U.S. Public Health Service studied the development of untreated syphilis in African American men over 40 years, never disclosing the purpose of the study and withholding treatment despite penicillin having been established as the standard treatment for syphilis over 20 years before the study ended.4

Today, it represents to African Americans the most widely-known example of the violation of trust on the part of the medical community. Former President Bill Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the U.S. Government and the American people to the study survivors and the African American community at large in 1997, nearly 25 years after the close of the study.5

It will forever be remembered as the longest nontherapeutic experiment on human beings in the U.S.

As a significant consequence of this mistrust, African Americans have not voluntarily enrolled in commensurate numbers in contemporary medical trials, in effect leaving an entire group behind in the wake of medical advancement, thereby serving to further widen the divide in health care equality.

The National Medical Association acknowledged this discrepancy in the enrollment of African American research participants in 1996 and identified the following major barriers to increasing representation: lack of awareness about trials, economic factors, communication issues and not surprisingly, mistrust.6

Given the noted exploitation and discrimination of African Americans for the advancement of medicine, it is incumbent on today's physician to be aware of this history and work harder to partner with our African American patients, understand their expectations, misgivings and their fears regarding the treatments we offer.

Only through a foundation built on increased sensitivity and the appreciation of this nuanced relationship with the African American community can physicians seek to establish and maintain the trust that is needed to effectively engage our patients.

Socioeconomic Barriers to Health Care Access

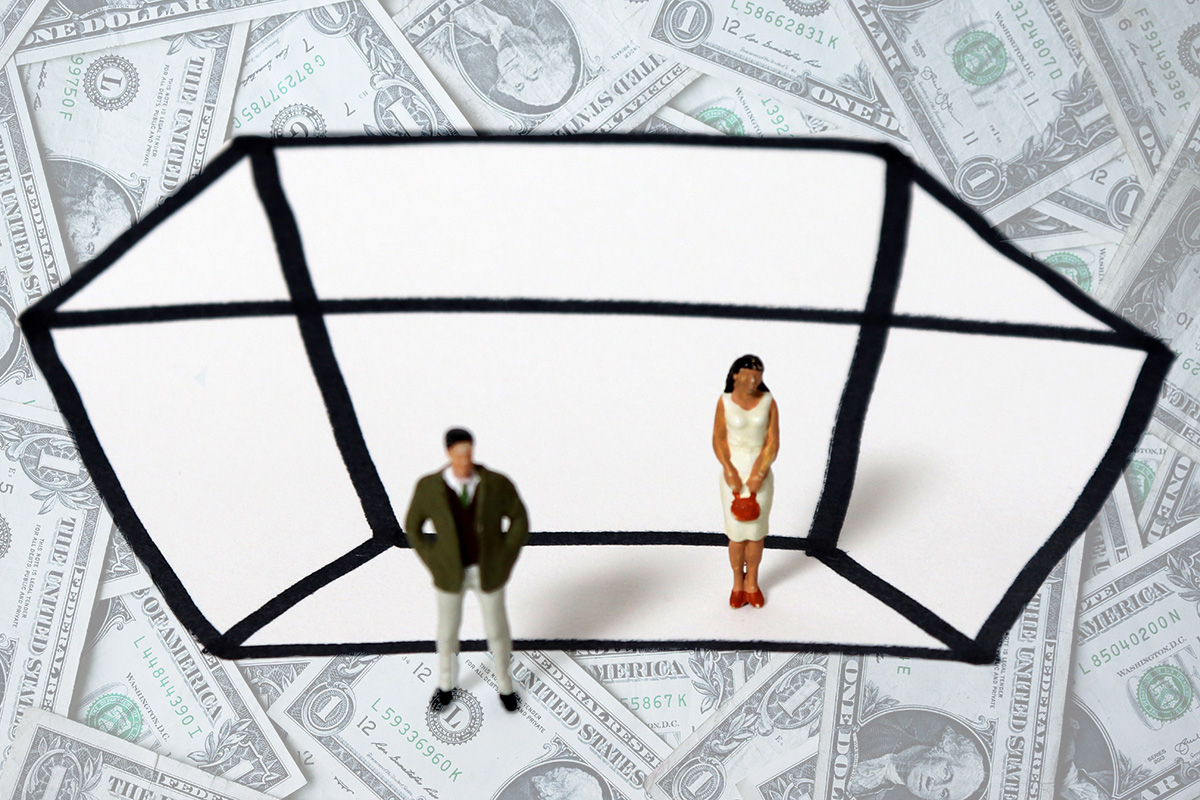

The stark socioeconomic inequalities experienced by the African American community diminish their access to necessary health care services and contribute to their disproportionately high rates of chronic illnesses.

According to the 2017 report on Health Insurance Coverage in the U.S. by the Health and Human Services Department (HHS), the average median household income for African Americans was $40,165, compared with $65,845 for white households.

Nearly 22.9% of African Americans lived at the poverty level compared with 9.6% of whites, with an unemployment rate of 9.5% for African Americans compared to 4.2% for whites.

Despite a lower annual household income, African Americans in general spent a larger percentage of their income on medical care, 16.5% vs. 12.2% for whites.

Just under one in five African Americans is uninsured as compared with one in eight whites, with about 33% of those uninsured persons suffering from a chronic condition, unfortunately making them nearly six-times less likely to receive care for their condition compared with an insured person.7

Furthermore, according to a recently published study that analyzed data from the National Medical Expenditure Survey from 2002-2015, being African American puts one at near a 12% decreased likelihood of having a primary care physician compared with their white counterpart.8

Moreover still, even those with a primary care physician typically experience a difference in the quality of the patient-physician relationship, with African American patients reporting less of a patient-centered approach along with increased physician verbal dominance and lower positive physician affect during their visits compared with their white counterparts.9

When emergency care is needed, African Americans are often directed to safety-net hospitals with limited resources.10

As a result of these socioeconomic challenges, the overall quality of health care that African Americans receive is not surprisingly worse when compared with white patients.11-13

As the above statistics demonstrate, African Americans represent an extremely vulnerable and disadvantaged community within our nation. It is imperative that physicians understand and appreciate the degree of leverage that is present against the delivery of successful health care to African American patients.

Lack of Progress in Resolving Health Care Disparities

The health care disparities experienced by African Americans are not new. The landmark 1985 Report on Black and Minority Health by the HHS, known as the Heckler Report, documented that inequalities in health care were responsible for over 60,000 excess deaths each year (predominately in African Americans), and emphasized the elimination of health care disparities as a national priority.

At the time, cardiovascular deaths in African Americans were 33% higher compared with the general population.14 In 2010, a review of the Heckler Report findings demonstrated no improvement in the disparity of cardiovascular deaths between African Americans and the general population.15

Due to these persisting inequalities, the HHS developed a strategic, five-year Disparities Action Plan to create "a nation free of disparities in health and healthcare."16

Concurrently, the Healthy People 2010 program similarly listed the elimination of health care disparities as one of its two goals.17 This goal was reinforced in the subsequent Healthy People 2020 and 2030 initiatives.18,19

Although significant efforts have been made to identify health care disparities in African Americans over the past 35 years, this has not yet translated into any meaningful improvement in disparities related to cardiovascular health.

Like police officers, physicians take an oath to "serve and protect."20 However, decades of systemic inequalities in law enforcement and successive, tragic deaths of black individuals have culminated in a tipping point, as represented by the current protests sparked by the death of George Floyd.

As a result, police brutality has become a public embarrassment and tragedy for all Americans. It is only a matter of time before the same systemic inequalities force us to reach the same tipping point in medicine.

As health care providers, we have been made well aware of the inequalities that exist within law enforcement as experienced by African Americans and also the lack of accountability for a system that fails to "serve and protect."

Yet at the same time, we also clearly see the inequalities that exist within health care and the failures of our own duty to safeguard, treat and improve the health of all our patients.

As the nation continues to move forward and unites together to manage this crisis, we must now ask ourselves: what is our accountability as physicians?

We must become more proactive in addressing the glaring disparities experienced by African Americans.

We cannot become complacent in only treating disease, but should challenge ourselves to address the societal barriers that contribute to poor health. We must make the dismal outcomes experienced by African Americans a clinical priority requiring immediate correction.

As physicians, we must uphold our oath.

References

- Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA 2020;323:1891-92.

- Sakalan, Leah. Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/rates.html. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- Mapping Police Violence. Police Violence Map. https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- Brawley OW. The study of untreated syphilis in the negro male. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phy. 1998;40:5‐8.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Presidential Apology. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/clintonp.htm. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- Harris Y, Gorelick PB, Samuels P, Bempong I. Why African Americans may not be participating in clinical trials. J Natl Med Assoc 1996;88:630‐4.

- United States Department of Commerce. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017. Accessed here June 7, 2020.

- Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics of Americans with primary care and changes over time, 2002-2015. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:463-6.

- Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health 2004;94:2084‐90.

- Hanchate AD, Paasche-Orlow MK, Baker WE, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with emergency department destination of emergency medical services transport. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(9):e1910816.

- Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1177-82.

- Sarrazin MV, Campbell M, Rosenthal GE. Racial differences in hospital use after acute myocardial infarction: does residential segregation play a role? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w368‐w378.

- Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, Birkmeyer JD. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1046‐53.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Report of the Secretary's Task Force on Black and Minority Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/checked/1/ANDERSON.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Part 2: Trends in Priorities of the Heckler Report. Accessed here June 7, 2020.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities: A Nation Free of Disparities in Health and Health Care. Accessed here June 7, 2020.

- Sondik EJ, Huang DT, Klein RJ, Satcher D. Progress toward the healthy people 2010 goals and objectives. Annu Rev Public Health 2010;31:271‐81.

- Hesse BW, Gaysynsky A, Ottenbacher A, et al. Meeting the healthy people 2020 goals: using the Health Information National Trends Survey to monitor progress on health communication objectives. J Health Commun 2014;19:1497‐1509.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030 Framework. Accessed here June 7, 2020.

- International Association of Chiefs of Police. Law Enforcement Code of Ethics. Accessed here June 7, 2020.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Anticoagulation Management, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, COVID-19 Hub, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Geriatric Cardiology, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Pericardial Disease, Prevention, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Valvular Heart Disease, Vascular Medicine, Anticoagulation Management and ACS, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Cardiac Surgery and SIHD, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Interventions, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, Acute Heart Failure, Pulmonary Hypertension, Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Angiography, Nuclear Imaging, Hypertension, Sleep Apnea, Sports and Exercise and Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Sports and Exercise and ECG and Stress Testing, Sports and Exercise and Imaging, Chronic Angina

Keywords: Acute Coronary Syndrome, Anticoagulants, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Cardiac Surgical Procedures, Metabolic Syndrome, Angina, Stable, Heart Defects, Congenital, Dyslipidemias, Geriatrics, Heart Failure, Angiography, Diagnostic Imaging, Pericarditis, Secondary Prevention, Hypertension, Pulmonary, Sleep Apnea Syndromes, Sports, Angina, Stable, Exercise Test, Heart Valve Diseases, Aneurysm, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Infections, Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications

< Back to Listings