Business of Medicine | Dyad Leadership Model: Walking the Talk

Governance and leadership are to an organization what an engine is to an automobile. Without a well-functioning one, neither will perform optimally.

As one health system board chairman said, "Without effective governance and leadership, nothing else matters." Without the infrastructure to competently execute, even well-considered strategic plans or detailed process improvement initiatives will languish.

Developing an appropriate governance and leadership foundation is a critical element of any high-functioning organization. Committing the time and effort to get it right is worth the investment and will pay dividends over time.

Given the complex nature of health care and the unknown "new normal" of a post COVID-19 world, effective governance and leadership is likely to become even more important than usual for organizational vitality. In some organizations, it may be required for viability.

This aspect of a health care organization is so critical that MedAxiom considers it the second foundational element of a high performing cardiovascular program, with only the organizational mission and vision ahead of it (Figure 1).

An organization's governance and leadership structure is responsible for embedding all the other necessary attributes to make it successful. With this heavy mantle, care must be taken to ensure it is expertly constructed.

The dyad leadership model has emerged as the best practice for guiding and managing health care organizations and, when practical, should be employed at each level of the institution.

MedAxiom believes strongly in this model and has put a dyad in place over the entire company. Its president is a practicing cardiologist and works with a team of administrative leaders at each level of the organization.

Similarly, the ACC, MedAxiom's parent company, also utilizes the dyad model at its helm.

Definitions

In health care, the dyad leadership model is best described as the pairing of a physician with a nonphysician administrator for strategic and operational oversight. With careful thought and attention, this leadership structure can be implemented at each level of organization.

Traditional departmental lines, whether in the practice or hospital, may no longer make sense, giving way to a more clinically oriented architecture. In cardiovascular medicine, care delivery has become increasingly subspecialized with complexity and dynamism in each area.

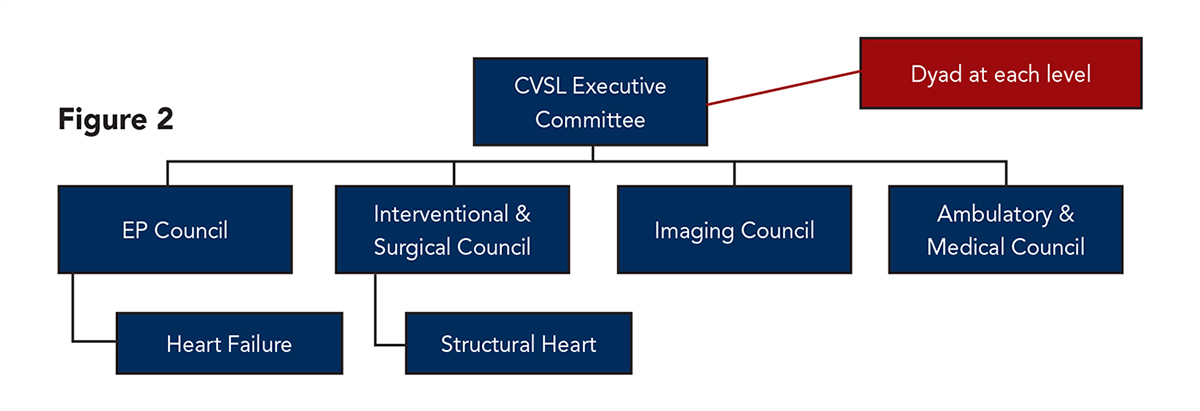

Establishing a governance structure that considers these unique subspecialty areas with dyad leaders at each level has proven an efficient and effective model (Figure 2).

In a dyad partnership, physicians assume primary responsibility for the clinical vision for the organization or subspecialty area and administrators operationalize the vision.

The visioning includes what services will be offered, where they can be done most effectively and by what providers, and the expectations for outcomes. Both leaders must contribute to garnering broad physician and nonphysician engagement as well as leading new program development as appropriate.

Administrators lead the organizational infrastructure, ensuring that the facilities and operations can achieve the desired clinical vision.

Their roles touch every aspect of the health care system from talent management to information technology, from regulatory compliance to third-party payer contracting, and from human resources to materials management and product procurement.

In tandem, the dyad will share responsibilities for strategic planning, capital and operational budgeting, and for setting the cultural tone for the organization.

Practical Guidance

Choosing the right people for the job is a critical step in creating a functional and effective governance structure. It has been said that a leader with no followers is just a person taking a walk.

Accordingly, getting the team to follow is a requisite attribute of leadership. This does not automatically come with years of service or a dominant personality. Myriad traits define an effective leader.

There is much scholarship devoted to this topic and consistent themes emerge to guide the search for leadership – particularly at the higher executive levels.

First, leaders must understand the vision for the organization and be able to inspire others to achieve it. This is consistent with MedAxiom's hierarchy of attributes for high functioning cardiovascular organizations. Inspiration requires enthusiasm and a positive outlook, since most worthy goals are not easily attained.

Communication is critical. Leaders must have the ability – and willingness – to regularly articulate the current state performance, celebrate victories and safely dissect shortfalls. This loop must be bi-directional so team members feel comfortable providing leaders feedback from all areas of the organization.

Leadership means doing what you say you'll do and playing by the rules that you set.

Finally, leaders must be able to make tough, smart decisions and stick to them. In some cases, quick action is required. In other situations, a slower, more deliberate process is prudent. Effective leaders will have the wisdom to know the difference.

Clearly not all physicians or administrators have the requisite skills, which is actually the point. Leadership is neither an easy task nor one for the masses; it is a special skill that few possess. High performing organizations carefully take the time to find them – and then institute a systematic process for preparing subsequent leaders.

Physician Dyad Leaders

The appropriate physician dyad leader will agree with the service line vision and be able to communicate it effectively. She or he must have a high degree of respect, not just for their clinical skills, but as a person as well.

If leading one of the subspecialty councils, the physician dyad should have a high level of training in that particular area (be an expert), have a passion for the clinical niche, and want to be in the role as a dyad.

Other important attributes include being a good communicator, considering her or his administrative dyad leader as a peer and not a subordinate, and following the established service lines rules and pathways.

She or he must lead by example.

Administrative Dyad Leaders

At the top level of the organization or service line, the administrative dyad leader should be someone who has a high level of authority within the organization. This is necessary both to make timely decisions and to have the ability to push past typical institutional barriers.

For larger integrated programs, the administrative lead is often an executive vice president or similar title with direct oversight of the entire cardiovascular service line. In a private cardiology practice, the dyad is logically the executive director or CEO for the group.

Like the physician lead, this person must be able to articulate the vision for the service line ("why this matters"), possess strong communication skills and be transparent.

When considering subspecialty units, the appropriate lead should have a certain level of authority over that clinical domain. For instance, for the Interventional and Surgical Council in Figure 2, the administrative lead might logically be the catheterization lab manager or the operating room manager.

This person should fully understand and appreciate the vision for the service line, be highly organized and given time and flexibility to perform the role. All too often an administrative dyad leader is assigned without this authority and a conflict in perceived priorities quickly comes to a head.

What Each Dyad Needs

Whether at the top of the organizational chart or at each of the clinical subspecialty units, administrative leads need access to their physician dyads and vice versa. A best practice is to create intentional and regular time together outside of the formal council or committee meetings to connect and synchronize priorities and activities.

In the majority of cases, the physician dyad lead will be a practicing doctor and – rightly – clinical needs will win out if there is a tug-of-war for time. It is unwise to leave the connections between dyads to chance meetings in the hallways, between cases, or for a few minutes following the monthly council meetings.

These impromptu touchpoints too often lead to disjointed communications, misunderstandings, inefficiency and suboptimal performance.

What the physician lead needs from his or her administrative partner is organization and efficiency.

As noted above, the physician dyad is most often a practicing clinician, so time is both precious and scarce. Administrative leads should organize their intentional dyad meetings to have agendas with predefined action outcomes. Data should always be used when available, be presented in a summarized and clear fashion, and support the actions that are the purpose of the meeting.

When organizational structures and decision matrixes come into play before decision execution, it is incumbent on the administrative lead to carefully explain this as part of the process and build in this time as part of any rollout plan. This will avoid frustration later.

Dyad partners must be able to trust each other and count on support in both good and bad times. Trust is something that must be earned and will take time to develop. This should be considered when initially pairing dyads. High-functioning dyads must be also transparent. Without the key ingredients of trust and transparency the effectiveness of a dyad team will languish.

Conclusion

The dyad leadership model has emerged as the best practice method for governing most service lines. However, simply putting dyad partners at each level of the organization will not guarantee success.

Careful consideration should be given to the architecture of the leadership model to appropriately distribute governance over the entire care spectrum and at a level commensurate with the size, scope and complexity of the program.

Once the organizational structure is created, careful attention should be paid to choosing the right people for each role and position identified.

It is essential that the leadership – both physicians and administrators – understand and can communicate the vision for the service line.

All parts of the program should recognize the vision and understand their respective roles. High levels of trust and transparency are required between dyad partners and should be easily recognizable throughout the organization.

A strong dyad leadership approach has never been more important than now, as the COVID-19 pandemic challenges the way cardiovascular care is delivered.

Together, physician and administrator leaders can shepherd their organizations through the transition and ensure success in the "new normal."

Clinical Topics: COVID-19 Hub

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Leadership, Fellowships and Scholarships, Insurance, Health, Reimbursement, Program Development, Goals, COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Motivation, Administrative Personnel, Operating Rooms, Clinical Competence, Frustration, Physicians, Pandemics, Government, Cardiology, Attention, Catheterization

< Back to Listings