Cover Story | Health Disparities and Social Determinants of Health: Time for Action

Health and the pursuit of it doesn't start in the clinic. The impact of homes, schools, workplaces, neighborhoods and communities readily outstrips the impact of the best that medicine can provide.

Given this, what's a doctor to do to ensure their care is as effective as possible? And how can the larger medical community work together to overcome the deleterious impacts of damaging social and physical environments?

As it turns out, clinicians and professional societies, like the ACC, can and are doing a good bit more than one might expect to promote health equity.

"There are definitely things we can all do on an individual level, whether it's in our offices or hospitals or our university divisions or departments. It's those moments where we can pause and question if we are practicing in an unbiased way and think about whether there's some small step we can make to achieve better health equity," says Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc, MACC.

This month Cardiology explores these questions with an eye to providing clear actionable steps forward. Steps that have become all the more important given the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities (see sidebar COVID-19: A Perfect Storm for Minority Populations).

Health Disparities 101

In times of crisis or calm, there are individuals who consistently experience health disparities, defined by Healthy People 2020 as "a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with economic, social, or environmental disadvantage."

Health and health care disparities are often viewed through the lens of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, but occur across multiple other dimensions, including age, geography, language, gender, disability status, citizenship status and sexual orientation.

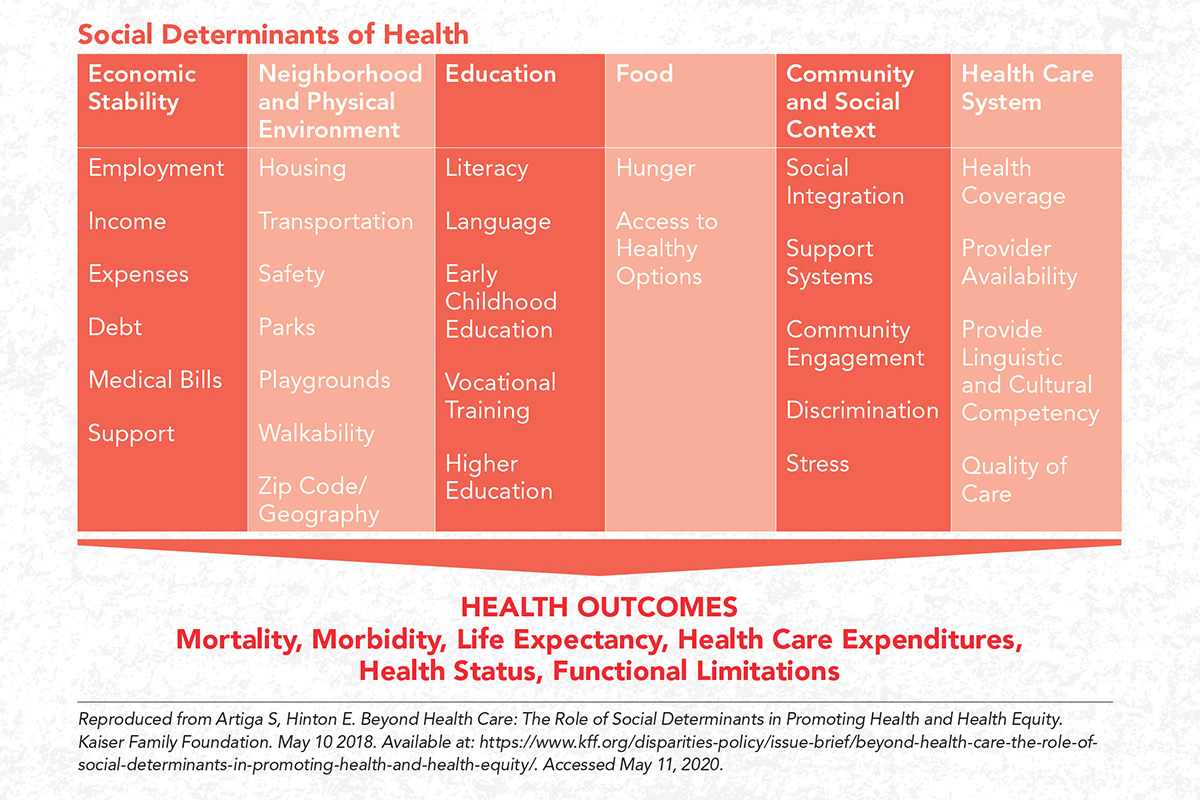

The complicated and interrelated factors that contribute to disparate health outcomes (and increased costs) are referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH).

As defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), SDOH are "the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.

"Health is maybe the only luxury we have and understanding all of its dimensions really takes us to a different place," says Yancy.

The impact of SDOH cannot be underestimated. In April, Madeline R. Sterling, MD, MPH, MS, and colleagues published a study of Medicare beneficiaries showing that, compared with those with none of the SDOH, the age-adjusted hazard ratio for 90-day mortality after hospitalization for heart failure for those with one SDOH was 2.89, rising only minimally to 3.06 for those with two or more SDOH.1

"This surprised us. We assumed that if you had two or more SDOH, your mortality risk would be much greater than if you had just one. But we found that having even just one put you at risk. This information might help us better understand which patients are most vulnerable to a poor outcome," says Sterling.

First Step: Ask

It's tempting to chalk up much of health disparity to poverty, which all agree is not something a physician can fix during a 15-minute clinical encounter. But this is overly simplistic, explains cardiology fellow Gmerice Hammond, MD, MPH.

"It's much more complex than that. We know that low-income white people have health outcomes that are similar with higher-income black people, and a black woman who has a college degree has the same chance of having an underweight or premature baby as a white woman who doesn't even have a high school education," she tells Cardiology.

"So, we see that race and socioeconomics interact in ways that aren't linear, meaning among other things, that poverty is not a uniform modifier of outcomes," says Hammond.

What she has a harder time understanding is why, since things like poverty, food insecurity, discrimination, poor health literacy and similar adverse life circumstances are well understood to have marked adverse impact on clinical outcomes, these factors are missing from standard risk models.

Her research is focused on how to properly measure SDOH and, more specifically, gaining an understanding of which factors matter most, are modifiable, and can be targeted by providers.

"Research has drawn an almost linear connection between tobacco and cardiovascular disease and as a result, smoking is included in our formal risk assessments. But we don't do this with social factors," she notes.

"This is a problem since we know that social determinants of health are more powerful predictors of cardiovascular outcomes than almost any other risk factor you can assess. How am I as a clinician supposed to understand your risk if I am missing important information on one of the most powerful predictors of that risk?"

Realizing that time is limited at the bedside and that it might be uncomfortable or daunting to ask about social factors without having a clear direction on what to do with that information, Hammond proposes a reductionist approach when considering social risk in clinical settings, detailed in a December 2019 Viewpoint article in JAMA that she co-authored with Karen E. Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, FACC.2

"Cardiovascular risk prediction models underpredict risk in populations with high social risk compared with those with low social risk," says Hammond. Adding SDOH to these models, even if only a few key factors such as poverty, may significantly improve risk assessment.

Indeed, in a just-published study, traditional risk factors explained only 40% of excess coronary heart disease events among those with low socioeconomic status, with the remaining 60% attributable to other risk factors.3

"It may turn out that we fashion a screening tool of one or two questions that could be used to trigger a referral for a more extensive assessment. This would then allow that information to be integrated into clinical workflow more efficiently," she adds.

Failing to do this, she warns, could mean persistent and widening health care inequities. "Current gold standard cardiovascular risk prediction models underpredict risk in the socially disadvantaged," says Hammond.

"If risk is systematically underpredicted, we will systematically undertreat."

The 2019 ACC/American Heart Association guideline for the prevention of cardiovascular disease recommend, for the first time, that clinicians consider social risk in their clinical risk assessment for cardiovascular events.

Hammond's approach, however, integrates this recommendation into a time-efficient and focused means of collecting and using the information to maximal impact.

Second Step: Care

"I think people underestimate the impact of empathy," says Hammond. Indeed, research shows that vulnerable populations experience greater harm from judgment and lack of empathy, a capacity that includes both cognitive and affective components.4

It's a two-way street: empathy also appears to counteract physician implicit bias.

Hammond notes it may be more effective to ask if there are ways the physician can help.

For example, for someone who is homeless, rather than a reminder to take the antihypertensives that were prescribed, try something like, "I know you have some housing and financial difficulties, and that must make it difficult to keep up with your medications. Let's see if there's a way we can get you taking this medicine because it's really important."

"I probably can't fix their homelessness and I might not even be able to fix their adherence issue. But I have strengthened the bond with the patient. This is important, because we know empathy improves adherence and satisfaction," says Hammond. It's also the human connection that makes us more effective physicians and caretakers, and this includes understanding their situation when assessing clinical risks, she notes.

For his part, Yancy thinks periodic self-reflection can have a measurable impact. "It's easy to think these issues are big problems that will require big initiatives to solve. But I think there is a lot an individual physician can do," says Yancy.

"Do some self-assessment and consider how you engage with each of your patients. Do you bring bias into the room? If you refer a patient for a procedure, how do you explain it this to the patient? How many of your patients are you referring for TAVR? Is there a bias there? And how many times do you sit down and listen to what you're hearing in their voice and hear what they're really saying? Are you comfortable that you're doing all this in a reasonable way?"

Yancy notes these same questions can be asked right up the line – in offices, divisions, guideline committees, etc., and in academic and private practice settings.

"We tend to put people in groups so we can quickly make certain deductions and, yes, sometimes we have to work harder to get that person a procedure or a certain drug. But this is the work that needs to be done if your goal is to get every patient on the best therapy for the right reason at the right time," he suggests.

ACC Targets Disparity From Multiple Directions

One way in which the ACC is tackling health disparities is through its to work to ensure a vibrant and inclusive workforce in cardiology.

"Our primary goal is to strengthen our workforce and become better scientists and clinicians because we come from a diversity of backgrounds and perspectives, and to be inclusive and make sure the profession is welcoming to everybody that wants to be part of it," says Pamela S. Douglas, MD, MACC, chair of ACC's Diversity and Inclusion Task Force.

This will, as a secondary follow on, likely improve efforts to reduce disparities. Douglas, however, is clear the goal is not to, for example, "suggest that only women can care for female patients or only African American physicians should take care of black patients."

Douglas thinks the College can do even more. "As a person, not as an ACC leader, I think there are ways the ACC could further elevate the concept of health equity," she says.

The NCDR, for example, is an incredible data resource, including data on patient and caregiver race and sex that is a rich source for looking at health disparities and outcomes following angioplasty, TAVR, etc., she adds.

She also highlights opportunities to address the financial burdens of young physicians with school debt.

"These are young physicians with school loans in the hundreds of thousands, which of course disproportionately affects those without rich parents. I think loan relief is something we could advocate for that would have a meaningful impact on our workforce."

"Within ACC there are a number of places across the mission areas where we could be more attentive and attuned to disparities and I'm hoping the conversations ongoing now within the College will bear fruit in this way," says Douglas.

"At a system level, I'd like to see health equity and a reduction in bias as a plain-spoken goal that we can all embrace," says Yancy.

"I think the ACC is well on their way to doing this with their focus on building a diverse face for cardiology but also in achieving diversity of thought, which we can use to elevate the challenges of different populations to an operational level."

"Time will tell, but I saw when I wrote in JAMA about this terrible situation with COVID-19 and African Americans, it resonated with people. I think it's given people a voice. This is our moment of ethical reckoning," says Yancy.

COVID-19: A Perfect Storm For Minority Populations

COVID-19 has laid bare health care disparities in the U.S. The illness caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has disproportionately impacted Americans who are black – and to a lesser extent Hispanics and other disadvantaged minorities – to a degree that has surprised even those well versed in these issues.

"It has been vicious. There's not another word I can use to qualify it," says Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc, MACC.

Take his hometown of Chicago as an example: black individuals make up about 30% of the population but, as of May 12, account for 48.8% of deaths. The damage started early: A recent piece in Propublica revealed 70 of the city's first 100 COVID-19 deaths were in black residents.5

Almost half of the population of the city is white (49.4%), but this group accounts for only 18.8% of COVID deaths. Across the state of Illinois, blacks account for 15% of the population, 19% of COVID-19 cases and 33% of deaths.

In some places the numbers look a bit better and in other places, worse.

In New York City, the pandemic's North American epicenter, blacks and Hispanic/Latinos appear to be sharing the burden. In data released May 6 that included both confirmed and probable COVID-19 deaths, they account for 30.2% and 30.7% of deaths, respectively, while being 24.3% and 29.1% of the city's population. Whites account for 27.5% of deaths in NYC, while being 42.7% of the population according to 2019 census figures.

In Louisiana, blacks are 13.4% of the population but 56% of COVID-19 deaths. The corresponding proportions for Hispanics are 18.3% (of population) and 1.75% (of COVID-19 deaths), but in another 17.26% of deaths, ethnicity was listed as unknown.

In Florida, Hispanics account for 26.1% of the population and 32% of cases and 21% of deaths. In Oregon, they are 13.3% of the population and 29% of cases. Countrywide data show a similarly troubling trend, with black populations and to a lesser extent Hispanics having a significantly greater relative risk of death than whites.

The most common reasons given for this imbalance include the usual tangle: Minorities are more likely to have risk factors for COVID-19 complications (hypertension, obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease) and are less likely to be afforded the "luxury" of staying home.

Layered on to this is the usual list of social determinants of health, including lacking health insurance, which may lead some to delay seeking testing or treatment, and that minorities are more likely to live in overcrowded or intergenerational households and work in low-paid people-facing jobs that put them at greater risk of extended contact with infected people.

Interestingly, while population density and older age have been considered important factors given the virus' uncanny ability to transmit itself among people in close proximity and its catastrophic effects on older individuals, this clearly isn't the whole story.

Manhattan has more than double the population density of the Bronx (71,434 people per square mile vs. 33,721) and a higher proportion of adults 65 years or older (16.5% vs. 12.8%), yet has seen a fraction of the deaths from COVID-19 (2,844 per 100,000 population vs. 4,599 per 100,000 population).6

"The Bronx is incredibly diverse – three-quarters of the people living in this community are racial or ethnic minorities. It also happens to be the poorest borough," says cardiologist and health services researcher Rishi Wadhera, MD, MPP, MPhil.

"We found that COVID-19 death rates were substantially higher in the Bronx than other less diverse and more affluent boroughs, like Manhattan."

"There are many layers to this story. For instance, nearly 75% of essential workers in New York City are racial or ethnic minorities who are keep the city running" he says.

Adds Yancy, "It's not just where you live but also how you live. The Bronx is all about minorities and poverty. So when you kind of depopulate the social determinants of health and look at the individuals pieces, you'll find pieces that don't align. When you put them all together, the poverty, the minority status, the geography, the density, you'll see a striking differential in the ability to be healthy as a function of who people are, where they live and how they live."

The "how you live" part is often overlooked, says Yancy.

"This crisis has shown us very well there are cultural activities that are considered inviolate – like worshipping together – that in fact threaten the health of communities."

The suffering is real, but the question is will we continue to allow it? As a physician, a health care leader, and a black man, Yancy has spent a good deal of time thinking about this question and feels hopeful the answer may finally be no.

"There are those who will say, gosh, this is awful, but there is just no way we can repair the social fabric. It is fatally frayed and fractured. I disagree. This is a country that has risen to the occasion to fight war and explore space, and this is yet another defined point in our society. If we recovered from 9-11 and found a new way to live, then we should recover from COVID-19 and find a new way to live," says Yancy.

"Instead of thinking about a new normal, I say let's target a better normal. A normal where we don't have so much vulnerability, where we have more respect for the importance of a viable public health enterprise, and a higher bar for what constitutes standard of health and health care," he adds.

"It will take investment, but mostly it will take a recalibration of our priorities – individually and institutionally – and a realization that we value having an enabled, healthy work force at all tiers and all economic strata contributing to our economic enterprise, and where we ensure that populations are not forgotten or left to experience disproportionate suffering."

Race/Ethnicity Among Risk Factors For Infection in UK

New COVID-19 data from the United Kingdom hints at the outsized impact of the virus on ethnic and racial minorities there too. In The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Simon de Lusignan, MD, MSc, and colleagues reviewed data from the first 3,802 people tested for SARS-CoV-2 within the Royal College of General Practitioners sentinel primary care surveillance network, a network of 500 general practitioners across England which are broadly representative of the population.7

Looking at data from 587 people with a positive COVID-19 test result and 3,215 with a negative result, the authors noted several trends:

- The median age of patients who had a test was 58.0 years for men and 51.5 years for women. Almost one-fifth of adults 75 years and older tested positive (19.5%) and fully 18.5% of those between the ages of 40 and 64 years tested positive, as compared with just 4.6% of children aged up to 17 years.

- Infection risk was higher in black people than white people (62.1% vs. 15.5%; adjusted odds ratio, 4.75) and higher in men than women (18.4% vs. 13.3%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.55).

- Individuals from deprived and urban areas were also more likely to be infected than those from higher income and nonurban areas.

Overall the numbers of black people in this study were small, meaning the results should be interpreted with caution, state the authors. They add though that the findings are consistent with a recent analysis of 3,370 people admitted to intensive care in the UK with confirmed COVID-19, which found that 11.9% were black, well above the 3.3% expected based on national figures.

References

- Sterling MR, Ringel JB, Pinheiro LC, et al. Social determinants of health and 90-day mortality after hospitalization for heart failure in the REGARDS study. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e014836.

- Hammond G, Joynt Maddox KE. A theoretical framework for clinical implementation of social determinants of health. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:1189-90.

- Hamad R, Penko J, Kazi DS, et al. Association of low socioeconomic status with premature coronary heart disease in US adults. JAMA Cardiol 2020;May 27:[Epub ahead of print].

- Lorié Á, Reinero DA, Phillips M, Zhang L, Riess H. Culture and nonverbal expressions of empathy in clinical settings: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:411-24.

- Eldeib D, Gallardo A, Johnson A, et al. COVID-19 Took Black Lives First. It Didn't Have To. ProPublica. Available here. Published May 9, 2020. Accessed May 11, 2020.

- Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P, et al. Variation in COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths across New York City Boroughs. JAMA 2020; April 29:[Epub ahead of print].

- de Lusignan S, Dorward J, Correa A, et al. Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 among patients in the Oxford Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre primary care network: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; May 15:S1473-3099(20)30371-6.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Anticoagulation Management, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, COVID-19 Hub, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Geriatric Cardiology, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Pericardial Disease, Prevention, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Valvular Heart Disease, Vascular Medicine, Anticoagulation Management and ACS, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Cardiac Surgery and SIHD, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Interventions, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, Acute Heart Failure, Pulmonary Hypertension, Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Angiography, Nuclear Imaging, Hypertension, Sleep Apnea, Sports and Exercise and Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Sports and Exercise and ECG and Stress Testing, Sports and Exercise and Imaging, Chronic Angina

Keywords: Acute Coronary Syndrome, Anticoagulants, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Cardiac Surgical Procedures, Metabolic Syndrome, Angina, Stable, Heart Defects, Congenital, Dyslipidemias, Geriatrics, Heart Failure, Angiography, Diagnostic Imaging, Pericarditis, Secondary Prevention, Hypertension, Pulmonary, Sleep Apnea Syndromes, Sports, Angina, Stable, Exercise Test, Heart Valve Diseases, Aneurysm, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Infections, Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications

< Back to Listings