Feature | An Update on Acute Mechanical Circulatory Support in Cardiogenic Shock

Absence of Evidence Base Supports a Patient-Centered Team Approach

Temporary mechanical circulatory support (MCS) is an attractive and intuitive option when medical approaches to supporting a weakened heart are insufficient. But while the field is a growing one, it is also one that has produced a jumbled evidence base for a range of devices and a smattering of indications.

"Randomized trial data are lacking for all devices and approaches, whether it's Impella or ECMO. The highest quality data we have to date for cardiogenic shock is coming from registries. Data are badly needed to clarify the role of acute MCS in cardiogenic shock," says Navin Kapur, MD, FACC, a dual board-certified interventional cardiologist and advanced heart failure/cardiac transplant specialist.

Kapur, who is the executive director of the CardioVascular Center for Research and Innovation at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, adds there are several important trials currently ongoing. The absence of data is reflected in current European guidelines, which recommend considering MCS in selected patients, without any preference for device selection (Class IIa, level of evidence C), according to a review on the topic by Holger Thiele, MD, from the Heart Center Leipzig at University of Leipzig, Germany.1

Trials are difficult in this area for a number of reasons, including difficulties in patient selection, timing and futility, but researchers are findings innovative ways to work around these impediments.

The lack of clear evidence of benefit hasn't seemed to adversely impact the business argument much. According to a recent market report, the percutaneous MCS devices market was valued at US$1,474.28 million in 2019 and is projected to reach US$3,964.75 million by 2027.2 The market is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 13.5% from 2020 to 2027.

"The growth rate, however, is contingent on ongoing trials being positive, theoretically at least. It's really hard to say where we'll be in five years with MCS," says Thiele.

"If all the ongoing trials and planned trials are positive, we will surely see a huge increase in the use of these devices. However, it may also be that these trials are neutral or even negative, showing harm with the use of MCS. In this case, there will be a decline in the use."

MCS and Cardiogenic Shock in a Nutshell

Cardiogenic shock is the clinical demonstration of profound depression of myocardial contractility, be it left, right or biventricular. It is a complex process, wherein inadequate cardiac output leads to reduced cardiac index, impaired systemic perfusion and end-organ hypoperfusion and dysfunction, often complicated by a systemic inflammatory response with severe cellular and metabolic abnormalities.

Between 70 and 80% of cardiogenic shock is due to acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and most of the rest occurs in patients with decompensated end-stage heart failure. The incidence of cardiogenic shock appears to be increasing while outcomes have remained stubbornly poor. Mortality after AMI-related cardiogenic shock (AMICS) is around 50% worldwide, but has probably decreased somewhat with widespread implementation of early revascularization.3,4

"From 1967 to 1999, survival from shock was about 20%. Now, even with two decades of advances in early revascularization, the implementation of regionalized MI systems of care, and the advent of mechanical circulatory support devices, survival now hovers around 50%," says Behnam Tehrani, MD, AACC.

Cardiogenic shock can quickly progress to multiorgan failure without assistance.

"This is a disease process in which patients progress down a proverbial death spiral over a very short period of time – minutes and hours, not days or weeks," says Tehrani, who is the medical director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at INOVA Heart and Vascular Institute in VA.

Temporary MCS to supplement cardiac output is most commonly used in the treatment of cardiogenic shock refractory to medical therapy. There are a number of MCS devices available, but the three most common platforms are the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), the percutaneous ventricular assist devices (VAD) (Impella, TandemHeart, and others), and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO).

The devices can be used in various configurations, alone or in combination with each other, and can provide right and/or left ventricular support. The difficulty is device selection in a field with a profound lack of randomized trial data.

There have been no randomized trials of current-generation MCS devices in the setting of high-risk PCI, and very few trials in cardiogenic shock. Most of the available evidence is from observational studies.

IABP-SHOCK II is a standout, one of the few, larger randomized trials and it was negative. First published in 2012, it examined the impact of the IABP in 600 AMICS patients.5 All patients were expected to undergo early revascularization (percutaneous or surgical).

The 30-day (39.7% and 41.3%), one-year (52% and 51%), and six-year (66.3% and 67%) mortality rates did not differ between the IABP arm and medical therapy (control) arm.6 There were no significant differences in secondary endpoints or in process-of-care measures, including time to hemodynamic stabilization or length of stay in the intensive care unit.

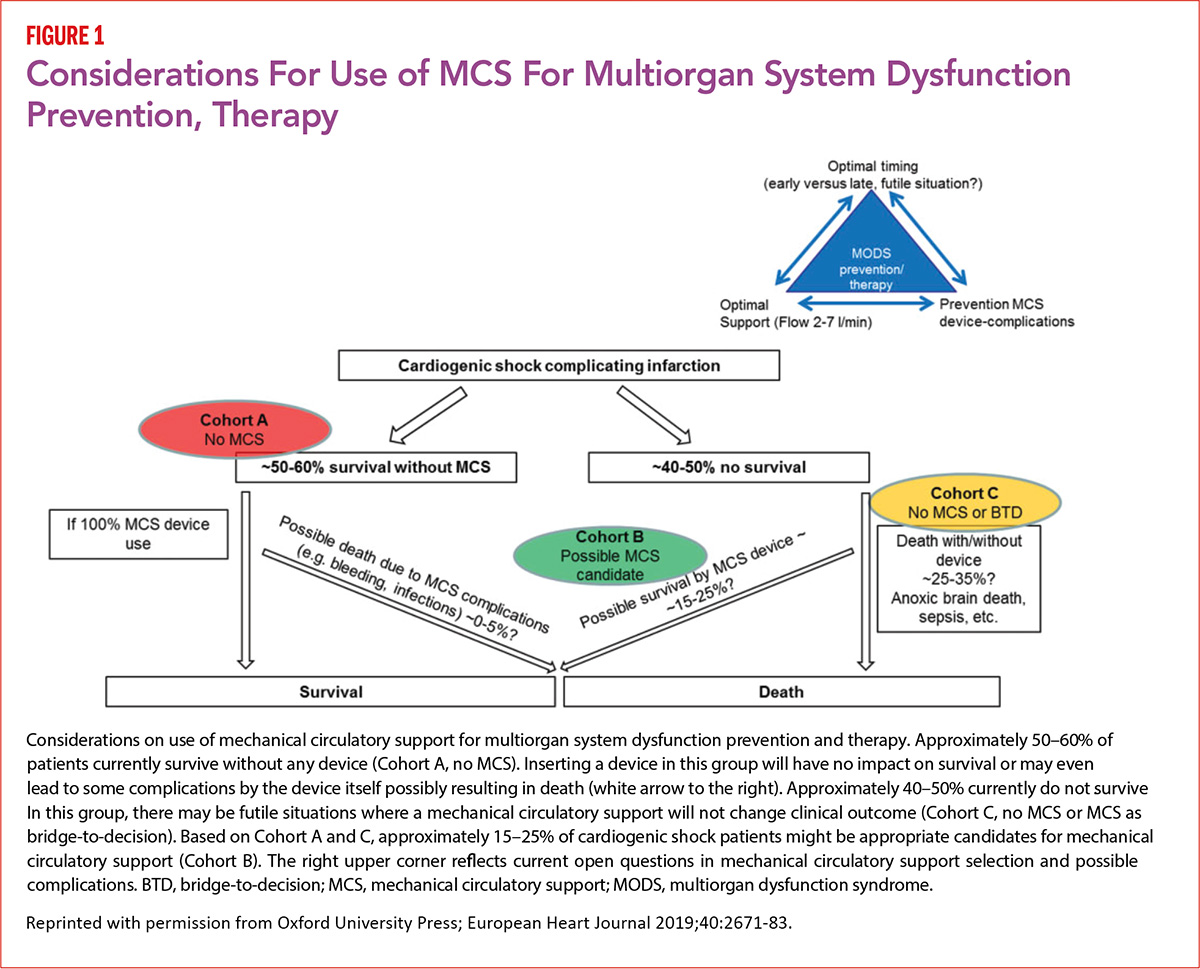

Based on data from IABP-SHOCK II, for which he was the principal investigator, Thiele suggests that between 50 and 60% of AMICS patients survive without any MCS device and inserting a device in this group will be of no benefit.1 In about 40 to 50%, death is likely to occur even with MCS, leaving a subgroup of 15 to 25% of cardiogenic shock patients where MCS could impact survival (Figure 1).

"Currently we do not have the evidence to clearly predict who will be the 50 to 60% who will survive," says Thiele. "We have some scores which give us information but these are not perfect and nobody has applied these scores in a prospective way to validate them for clinical decision-making such as for MCS use."

He'd like to see more trials. "And we have to go into these trials not prejudiced that MCS is beneficial." Because regulatory agencies have approved the devices without proof of survival benefit, he further suggests that the onus is on physicians to insist on developing a solid evidence base.

"The device makers are not really interested in proving that these devices improve survival as long as it is only required by regulation to show some impact on blood pressure and some limited safety data. However, we as physicians together with the European Medicines Agency and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should ask for more data to really show the benefit," says Thiele.

As for Impella, a percutaneous VAD, despite an FDA indication for shock based on a large registry study, there are no data showing it improves survival any more than an IABP. The 2006 ISAR-SHOCK trial was small and showed that Impella improved hemodynamics compared to IABP, which is not surprising since it provides greater flow in a manner less dependent on native cardiac output and directly unloads the left ventricle.7

However, it did not improve survival. On the other hand, the IMPRESS in Severe Shock trial, using the Impella CP in comparison to IABP in 48 patients, did not show any benefit on hemodynamic variables or lactate and once again did not show a survival benefit.8

More recently, Amin, et al., used data from the Premier Healthcare database and propensity-matching to show that Impella use is rapidly increasing but associated with higher odds of death, and wide variation in bleeding and stroke.9

And in February, Sanket Dhruva, MD, FACC, and colleagues published an analysis in JAMA that used the CathPCI and the Chest Pain-MI registries, both part of the ACC's NCDR, and showed that patients treated with Impella had higher in-hospital mortality compared to balloon pump.10

"These studies raise questions regarding the safety profiles of these devices and they highlight the need for adequately powered randomized controlled trials to evaluate both safety and efficacy," says Tehrani.

Besides lacking compelling evidence of benefit, Impella has been linked to a greater risk of complications. Dhruva, et al., reported a 31.3% rate of major bleeding with Impella compared to 16.0% for IABP (p<0.001).

In comments to Cardiology, Kapur noted these findings highlight important safety concerns among real-world patients treated with short-term MCS, such as ECMO or Impella, but must be interpreted with caution because the authors were unable to fully adjust for shock severity.7

"We're seeing increased use in ECMO and Impella in shock, but the tricky part of course is how you decide which patient gets which device. Remember, these are fairly large bore devices – ECMO ranges on the arterial size from 15 French to 21 French and that's a big hole in your artery. Impella is 14 French, still much larger than a balloon pump which is about 9 French," he adds.

According to Tehrani, there is similarly no randomized controlled data on the TandemHeart and limited data on ECMO, although for the latter there are several ongoing trials evaluating clinical efficacy.

The Plural of Anecdote is Not Evidence

It's been suggested that maximal medical therapy (volume resuscitation, vasodilators, inotropic agents) is not considered a justifiable endpoint for refractory circulatory shock, at least in well-resourced health settings.16

Asked to comment on alternatives to Impella, Kapur notes that even in countries that can't afford the device, faced with a patient with refractory cardiogenic shock, clinicians will often use balloon pumps or ECMO.

"It's a challenging situation because the engineering and the utilization of these devices is outpacing the evidence," says Kapur.

"They may not want to admit it, but a lot of people don't want to randomize patients because they basically feel that if you think the patient in front of you will benefit more from an Impella than a balloon pump, it would be wrong to enroll them in a trial. But we need people to understand that you can't just go by anecdote. We have to do these randomized trials or the field will continue to be a highly debated space and we will miss an opportunity to move the dial forward for patients."

Look at the Patient, Not the Device

In the absence of clear evidence supporting the use of any of the available MCS devices, a move is afoot to consider patient-centered standardized care, rather than promoting one device over another.

"What we've also come to realize is that when we become device agnostic and shift to being patient-centered, where we seek to better define the patient and better define the algorithm for treating specific subtypes of patients, then we can move the dial on mortality," says Kapur in an interview.

An issue with both ISAR-SHOCK and IMPRESS was the lack of a protocol to support initiation timing, the so-called door-to-support time, or device weaning, he adds.

"In the absence of randomized controlled trials to inform management, we are starting to see protocols being developed to standardize patient selection and care," says Tehrani.

There is also the hope that defining selection criteria and refining clinical criteria will, ultimately, inform the development of well-powered, informed randomized controlled trials.

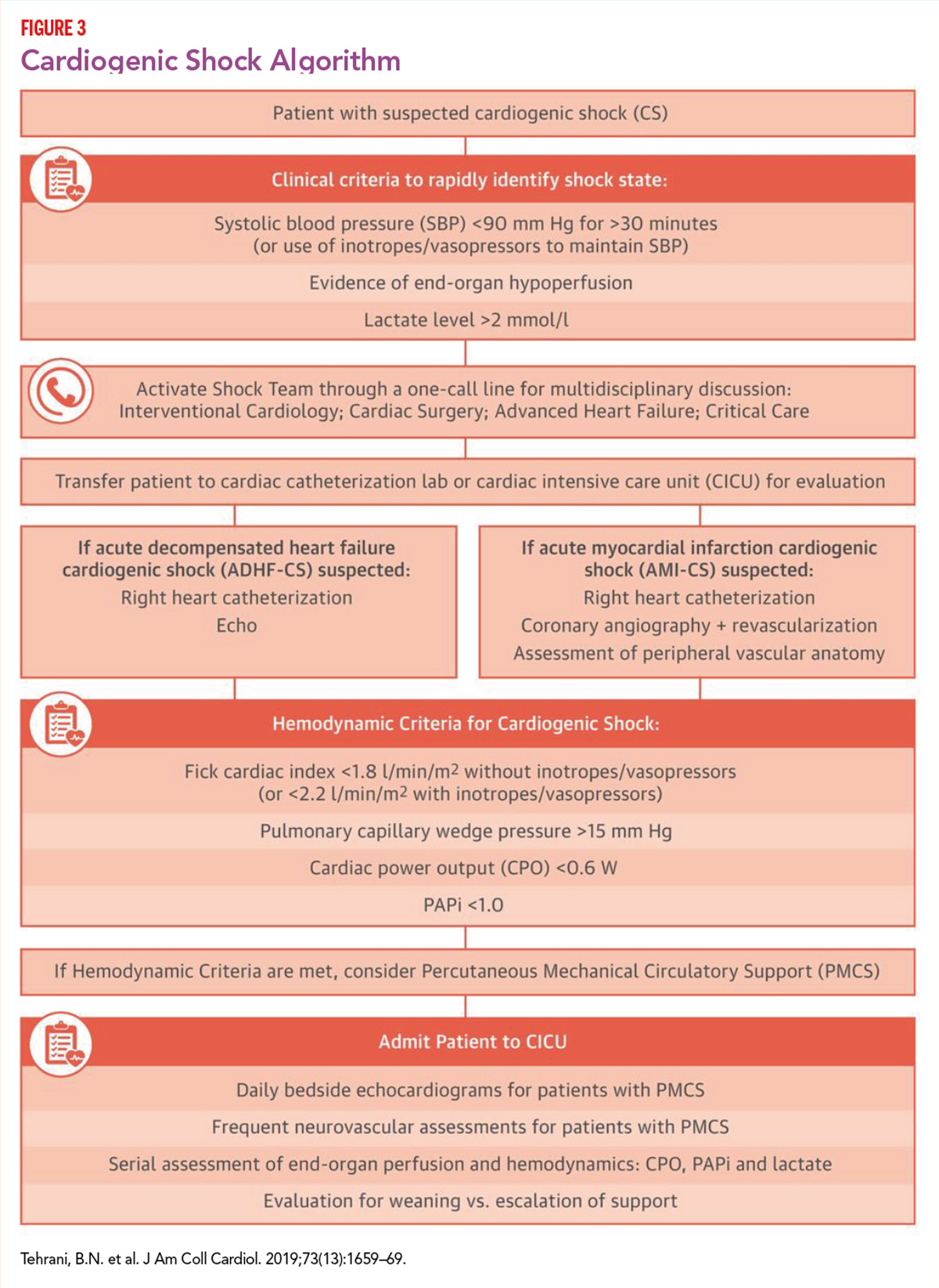

Kapur and colleagues designed an AMICS treatment algorithm that emphasized rapid identification and cath lab activation in AMICS, invasive hemodynamic monitoring to assess the need for MCS escalation and to safely and rapidly wean off inotropes, and early initiation of MCS.

In results published last year, use of a protocol involving hemodynamic guidance, now called the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative (NCSI), was associated with an impressive 72% rate of survival to discharge, well above that seen in historical controls.11 The majority of patients (92%) were supported with the Impella CP.

Protocol objectives were met in most patients, with 74% of patients receiving MCS prior to PCI and a mean door-to-support time of 85 minutes. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring was done in 92% of patients and patients surviving to device implantation had improvements in hemodynamics.

Unlike in heart failure, where a clear disease classification scheme exists and is widely used both clinically and for research purposes, shock lacks a clear way of determining and communicating severity.

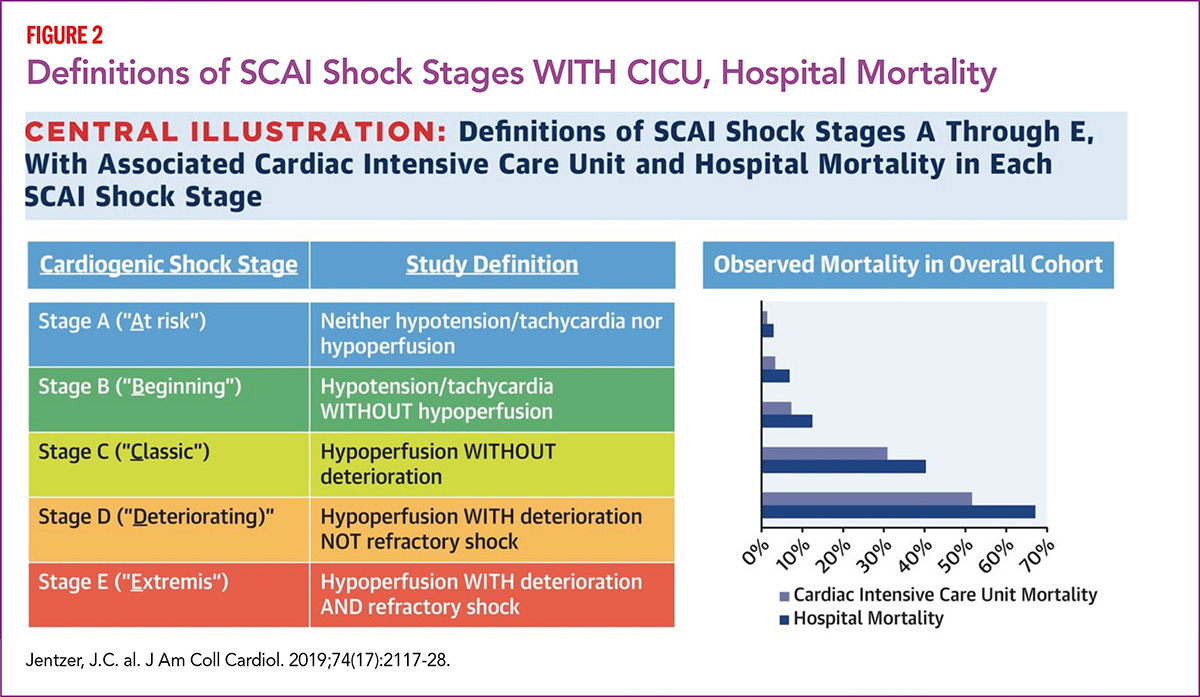

To fill this gap, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention (SCAI) recently proposed a new five-stage CS classification scheme, endorsed by four other organizations including the ACC.12

When retrospectively analyzed in over 10,000 Mayo Clinic CICU patients admitted from 2007 to 2015 (with shock stages classified retrospectively using admissions data), unadjusted hospital mortality rose from 3.0% for Stage A to 67.0% for Stage E (p<0.001) (Figure 2).13

Considering just SCAI stages C, D and E, mortality increased from 12.4%, to 40.4%, to 67.0%, respectively.

After multivariable adjustment, each higher SCAI shock stage was associated with increased hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio, 1.53-6.80; all p<0.001) compared with SCAI shock Stage A. Results were consistent in patients with acute coronary syndrome or heart failure.

"The study highlights and confirms what we saw in the IABP-SHOCK II trial, which is that it's inappropriate to group all cardiogenic shock patients together when deciding treatment and certainly when reporting mortality," says Kapur.

"Rather, patients should be grouped according to risk at presentation and the underlying disease process."

Teamwork Makes the Dream Work

Patient with cardiogenic shock often have a dynamic pathophysiology and a rapidly evolving hemodynamic clinical picture. Along the way, other insults can occur – arrhythmias, vasodilation, ischemia and infection – that acutely change the trajectory of the disease. Early diagnosis and directed therapy is crucial, but so is the ability to anticipate possible patient trajectories and manage the noncardiac complications related to shock.14

Team-based cardiogenic shock care is a sister approach to standardized, device-agnostic care and something that is picking up worldwide.

"Shock Teams" can include specialists from interventional cardiology, critical care medicine, heart failure, anesthesiology, cardiothoracic surgery, perfusion services, nursing and rehabilitation.

"Outcomes for disease processes, such as trauma, sepsis, stroke and tumors, have improved with the implementation of a team-based approach to management. In our institution, we have adopted a similar multidisciplinary approach and we have seen significant improvements," says Tehrani.

By all appearances, team care appears to improve outcomes in cardiogenic shock. Tehrani's group published an observational study last year showing that a standardized team-based approach to management can improve outcomes substantially (Figure 3).15

In their study, 204 patients with CS (AMI related to acute decompensated heart failure) were treated by a multidisciplinary shock team using a standard protocol that emphasized early identification of shock, mandatory invasive hemodynamic monitoring, minimal use of vasopressors and inotropes, and early MCS. The shock team was able to choose between multiple MCS modalities.

Thirty-day survival improved from 47% in 2016 to 57.9% in 2017 and 76.6% in 2018 (p<0.01). The researchers used logistic regression analysis to develop a validated risk score using seven risk factors found to be independent predictors of 30-day mortality.15 The score showed good discrimination with an area under the curve of 0.97.

Asked for an example of the benefit of coordinated care, Tehrani listed several possible scenarios.

"Say you're the interventional cardiologist with a STEMI patient in the lab and you're considering using an MCS device. You might discuss the options with the cardiac surgeon, who may set some treatment goal posts, noting that if a specific amount of support isn't gained, an ECMO or some other higher level device would be used. At the same time, the heart failure specialist might want to start considering this patient for a transplant listing or an LVAD, while the intensivist might be noting that the patient has renal dysfunction or respiratory failure, which they're going to try to get on top of as soon as possible," says Tehrani.

"The point is to have a shared decision-making model where all the bases are covered and everybody understands clearly what are the treatment objectives for each individual patient."

The field eagerly awaits results from several ongoing trials, in particular the DanGer Shock trial that will enroll 360 AMICS patients from five Danish centers and test the Impella CP device against guideline-directed medical therapy. Two other ongoing trials, EURO SHOCK and ECLS-SHOCK, will randomize 428 and 420 patients with AMICS, respectively, to early intervention with ECMO therapy or standard medical therapy.

"Until we have randomized evidence supporting the use of MCS devices for all-comer shock patients, we will need to continue to focus on care driven by a team-based approach and management algorithms," says Tehrani.

References

- Thiele H, Ohman EM, de Waha-Thiele S, Zeymer U, Desch S. Management of cardiogenic shock complicating myocardial infarction: an update 2019. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2671-83.

- Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices Market Share to Surpass US$ 3,964.75 million By 2027. MarketWatch. Accessed here on June 30, 2020.

- Hajjar LA, Teboul J-L. Mechanical circulatory support devices for cardiogenic shock: State of the art. Crit Care 2019;23(1):76.

- Mandawat A, Rao SV. Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices in cardiogenic shock. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10(5):e004337.

- Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann F-J, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1287-96.

- Thiele H, Zeymer U, Thelemann N, et al. Intraaortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2019;139:395-403.

- Whitehead E, Thayer K, Kapur NK. Clinical trials of acute mechanical circulatory support in cardiogenic shock and high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2020;35(4):332-40.

- Ouweneel DM, Eriksen E, Sjauw KD, et al. Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support versus intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:278-287.

- Amin AP, Spertus JA, Curtis JP, et al. The evolving landscape of impella use in the United States among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with mechanical circulatory support. Circulation 2020;141:273-84.

- Dhruva SS, Ross JS, Mortazavi BJ, et al. Association of use of an intravascular microaxial left ventricular assist device vs intra-aortic balloon pump with in-hospital mortality and major bleeding among patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. JAMA 2020:Feb. 10:[Epub ahead of print].

- Basir MB, Kapur NK, Patel K, et al. Improved outcomes associated with the use of shock protocols: updates from the national cardiogenic shock initiative. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019;93:1173-83.

- Baran DA, Grines CL, Bailey S, et al. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock: This document was endorsed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in April 2019. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019;94:29-37.

- Jentzer JC, van Diepen S, Barsness GW, et al. Cardiogenic shock classification to predict mortality in the cardiac intensive care unit. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2117-28.

- Vallabhajosyula S, Barsness GW, Vallabhajosyula S. Multidisciplinary teams for cardiogenic shock. Aging 2019;11:4774-76.

- Tehrani BN, Truesdell AG, Sherwood MW, et al. Standardized team-based care for cardiogenic shock. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1659-69.

- Shekar K, Gregory SD, Fraser JF. Mechanical circulatory support in the new era: an overview. Crit Care 2016;20.

Clinical Topics: Cardiac Surgery, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Acute Heart Failure, Heart Transplant

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Shock, Cardiogenic, Patient Selection, Medical Futility, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Registries, National Cardiovascular Data Registries, Heart Failure, Heart Transplantation, Longitudinal Studies

< Back to Listings