Web Exclusive Feature | Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: The Journey From the Patient’s Perspective

Abstract

Background: Much is known about management and treatment gaps for patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). Gaining insight into patients' perspective of their ADHF journey can help to design effective patient-centered care.

Objectives: This study aims to use patients' perspective to identify actionable items for improving heart failure care.

Methods: We used three different commercial patient panels to conduct 48-item online survey of ADHF patients in May-July 2014. Inclusion criteria consisted of patient age ≥50, hospitalization for ADHF within 4 months of survey, and persistent heart failure (HF) symptoms.

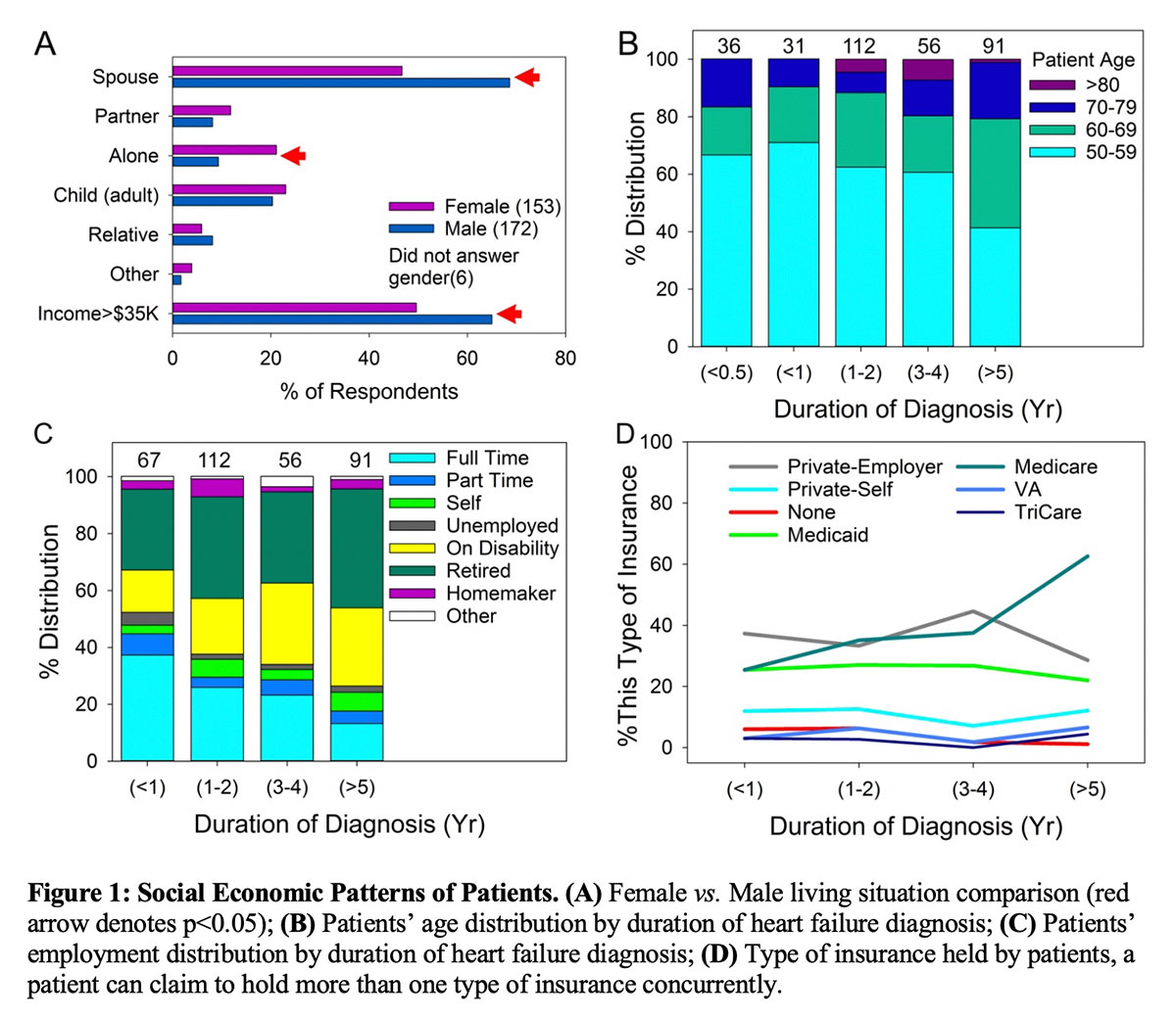

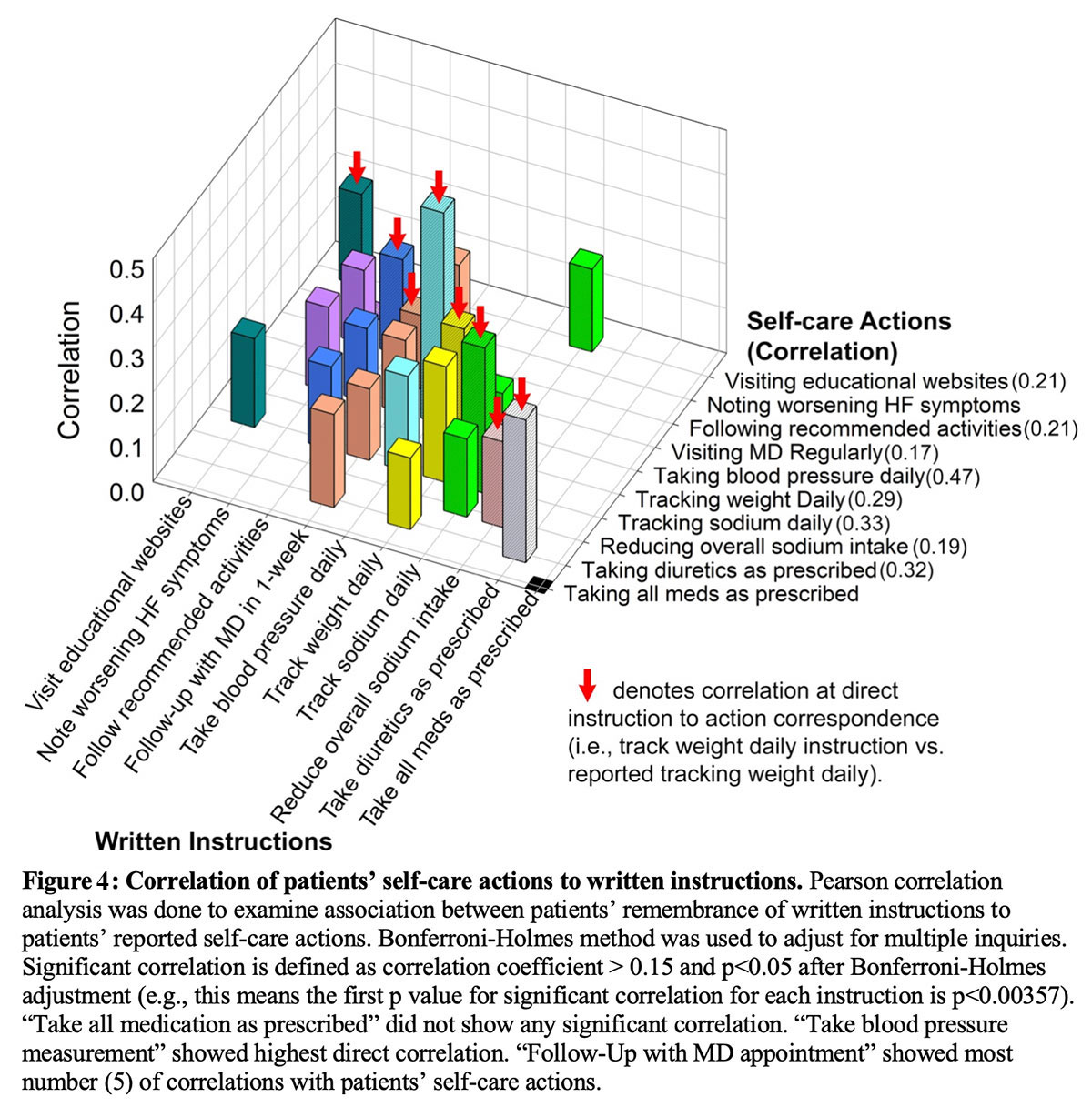

Results: Of 14,390 respondents, 331 met the inclusion criteria. 52% of respondents were men, 46% women, and 2% did not answer. Women were more socio-economically disadvantaged (living alone: men 9%, women 21%, p=.01; household income >$35,000/year: men 63%, women 49%, p=0.05). 79% of patients expressed confidence in knowing when ADHF is occurring. 79% of patients sought help within 12 hours upon experiencing decompensation. However, patients reported low performance of self-care that did not improve with HF duration (<1 year vs. >5 years: tracking daily weight 52% vs. 53%, seek help for fluid weight gain 49% vs.44%). We performed discharge instructions to self-care actions correlation. The top 4 instruction-to-action correlations were taking daily blood pressure measurements (r=0.474, p<0.000001), tracking daily sodium (r=0.326, p<0.000001), taking diuretics as prescribed (r=0.320, p<0.000001), and tracking daily weight (r=0.291, p<0.000001).

Discussion: Effective patient-centered care needs to address socio-economic difficulties and improve patients' ability to perform self-care.

Practical Value: Understanding patients' perspective can assist providers and patients' in creating sustainable, high value, actionable items for self-care of ADHF. Our study shows patients are willing to perform these items if they remember the instructions.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) continues to be a growing health issue in the U.S. with an estimated prevalence of 5.7M and incidence of 915,000 in 2016.1 HF has an estimated global prevalence of 38M-41M.2,3 Despite treatment advances and decline in death rates, the age adjusted HF death rate within the US has increased from 81/100,000 in 2012 to 84/100,000 in 2014.4 Although innumerable preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted focusing on therapies and outcomes, few have addressed patient reported health information (PRHI). Incorporation of PRHI into the assessment of HF treatment may provide more timely and actionable interventions.5

Careful medical management and self-care have been demonstrated to improve outcomes, including survival, functional status, and quality of life.6-8 In 2001, the Institute of Medicine defined patient-centered care (PCC) as "care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions."9 PCC focuses on the patient, not the disease nor the health delivery system.9 With PCC, the patient is provided information to facilitate participation in decision-making in his/her medical care. Quality of life of HF patients has been demonstrated to improve with PCC.10 However, recent HF clinical trials with objective measurements show that current implementations of PCC have not improved patients' quality of life perception.11,12 Thus, greater understanding of these inconsistencies is needed.

Understanding patients' perspective in their journey with ADHF may help the medical community to design better patient-centered HF care. This study reports patients' experiences of ADHF and self-care actions.

Methods

A 48-item online survey was conducted through three different consumer panels by the American College of Cardiology (ACC). Chesapeake Bay Institutional Review Board Services conducted the independent review and approved the protocol used for the study. Patient inclusion criteria consisted of: age ≥ 50 years, symptomatic HF as defined by - "experienced regularly and with severity" at least two of the symptoms ("shortness of breath (dyspnea) when sitting upright or lying down"; "swelling (edema) in your legs, ankles and feet"; and "sudden weight gain from fluid retention"), had been hospitalized for ADHF within the previous 4 months of the survey. The survey was conducted May to July 2014. The inclusion criteria were met by 331 patients out of 14,720 respondents who completed the questionnaire. True response rates cannot be calculated since the totality of patients who met the inclusion criteria is unknown.

Three panels composed the study population. 279 out of 2,455 respondents in the Research Now panel met inclusion criteria. 30 out of 9,459 respondents from the Toluna panel and 22 of 2,476 respondents from the Harris Poll panel met the inclusion criteria.

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS. Only gender and HF duration groupings had adequate numbers for meaningful statistical analyses. Independent z-tests were used to identify significant differences in proportional findings between groups (e.g., what % of women lived with spouse in comparison to men). Pearson correlation was used to identify association between variables (e.g., correlate remembered discharge instructions to reported self-care actions). When appropriate, Bonferroni-Holmes method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. Paired-t tests were used to compare admission and post-discharge results from the same respondents. Statistical significance is set at p≤0.05.

Results

Demographics

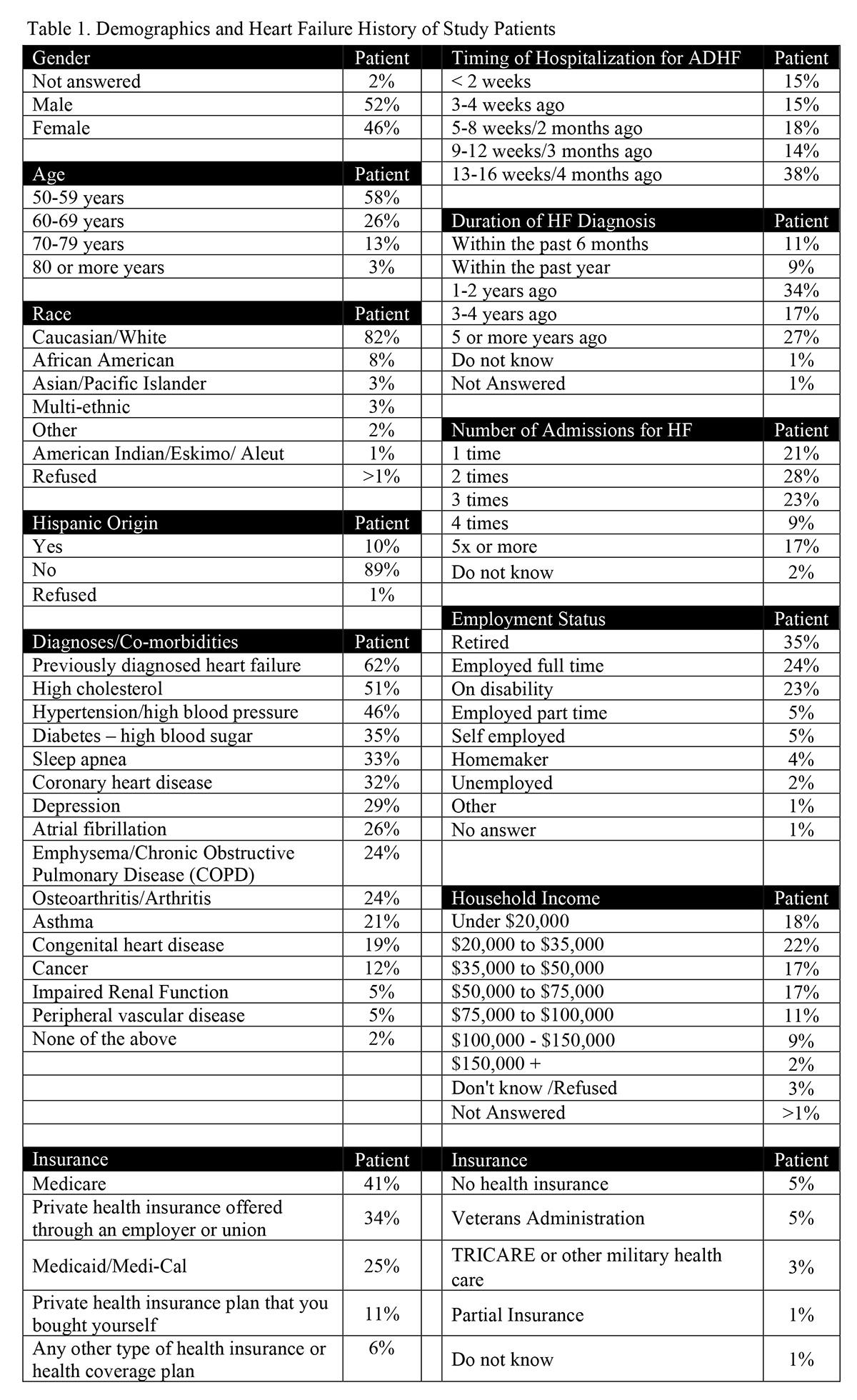

Gender was nearly even split: 52% were male and 46% were female with 2% unanswered. The majority of respondents were identified as Caucasian (82%), whereas 10% indicated Hispanic origin, and 8% identified as African Americans. Age distribution consisted of 50-59 years at 58%, 60-69 years at 26%, and ≥70 years at 16%. A majority of respondents (62%) indicated having been diagnosed with HF prior to the qualifying hospitalization. Frequently occurring diagnosed comorbidities (i.e., >25% of respondents) include high cholesterol (51%), hypertension (46%), diabetes (35%), sleep apnea (33%), coronary artery disease (32%), depression (29%), and atrial fibrillation (26%). A substantial number of respondents (27%) carried a diagnosis of HF ≥5 years. HF hospitalization were common with 17% of respondents reporting 5 or more previous hospitalizations (Table 1).

The majority (58%) reported annual income ≤ $50,000/year, which fell below the 2014 US median income of $53,657.13

Social and economic disparities existed between male and female respondents (Figure 1A). Men were more likely to live with a spouse (men: 69% vs. women: 46%, p=0.001) and women were more likely to live alone (men: 9% vs. women: 21%, p=0.01). A greater percentage of men had household income >$35,000/year than women (men: 63% vs. women: 49%, p=0.05). A far greater portion of women respondents (46%) lived in a household with income <$35,000/year than the general US population (21%).13 Five percent of women did not answer the income question.

Duration of heart failure diagnosis correlated with both age and economic status (Figure 1B-D). Respondents with HF duration <1 year consisted of predominantly those in the 50-59-year-old age group (67%). Respondents with HF duration >5 years largely comprised those age ≥ 60 years (59%). Full time employment decreased from 39% at <1 year of HF duration to 13% at >5 years of HF duration, which negatively correlated with duration of HF diagnosis (r= –0.154, p=0.005). This negative correlation remained even after adjusting for age (r= –0.118, p=0.032), making HF duration a separate and independent contributor to loss of full time employment in addition to age. The binary nature of the data depressed the magnitude of correlation coefficient r. Combined retirement and disability status grew from 42% to 69% from <1 to > 5 years of HF duration. The portion of patients using Medicare increased with from 25% to 63% from <1 to >5 years of HF duration.

Patients' Perspective

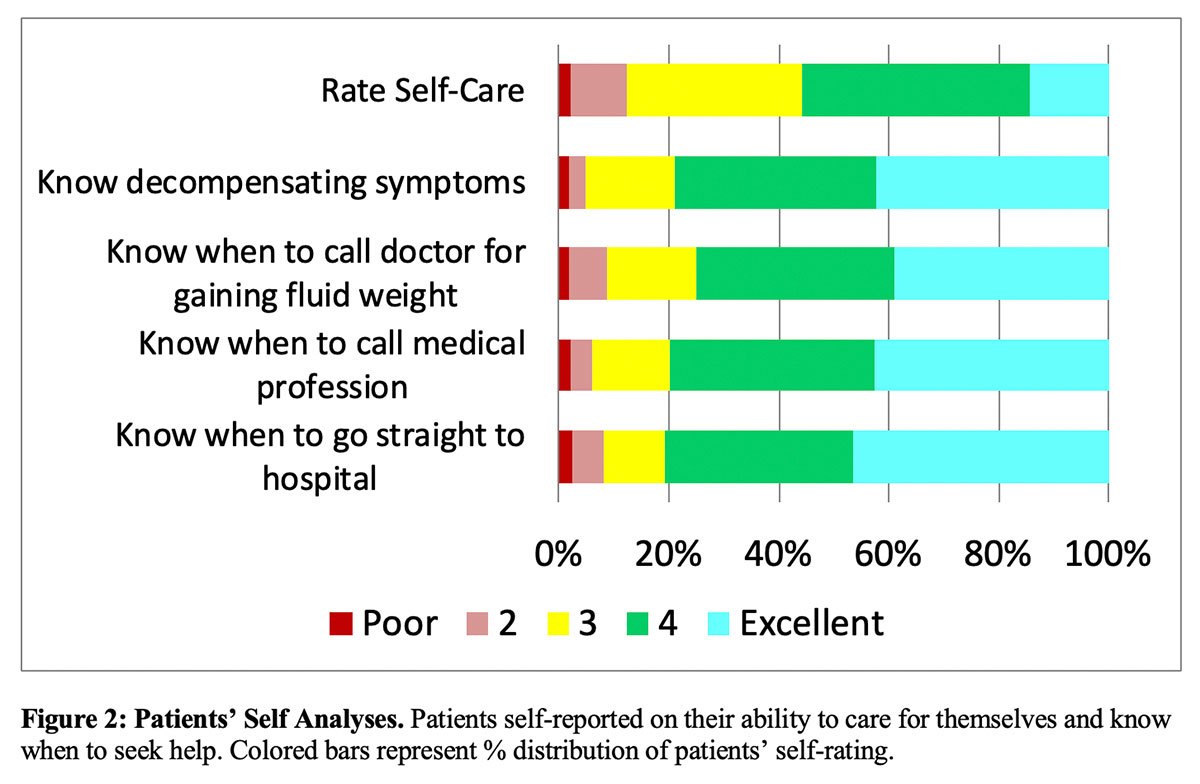

In general, respondents expressed confidence in knowing when HF decompensation occurs and when to seek help (Figure 2).

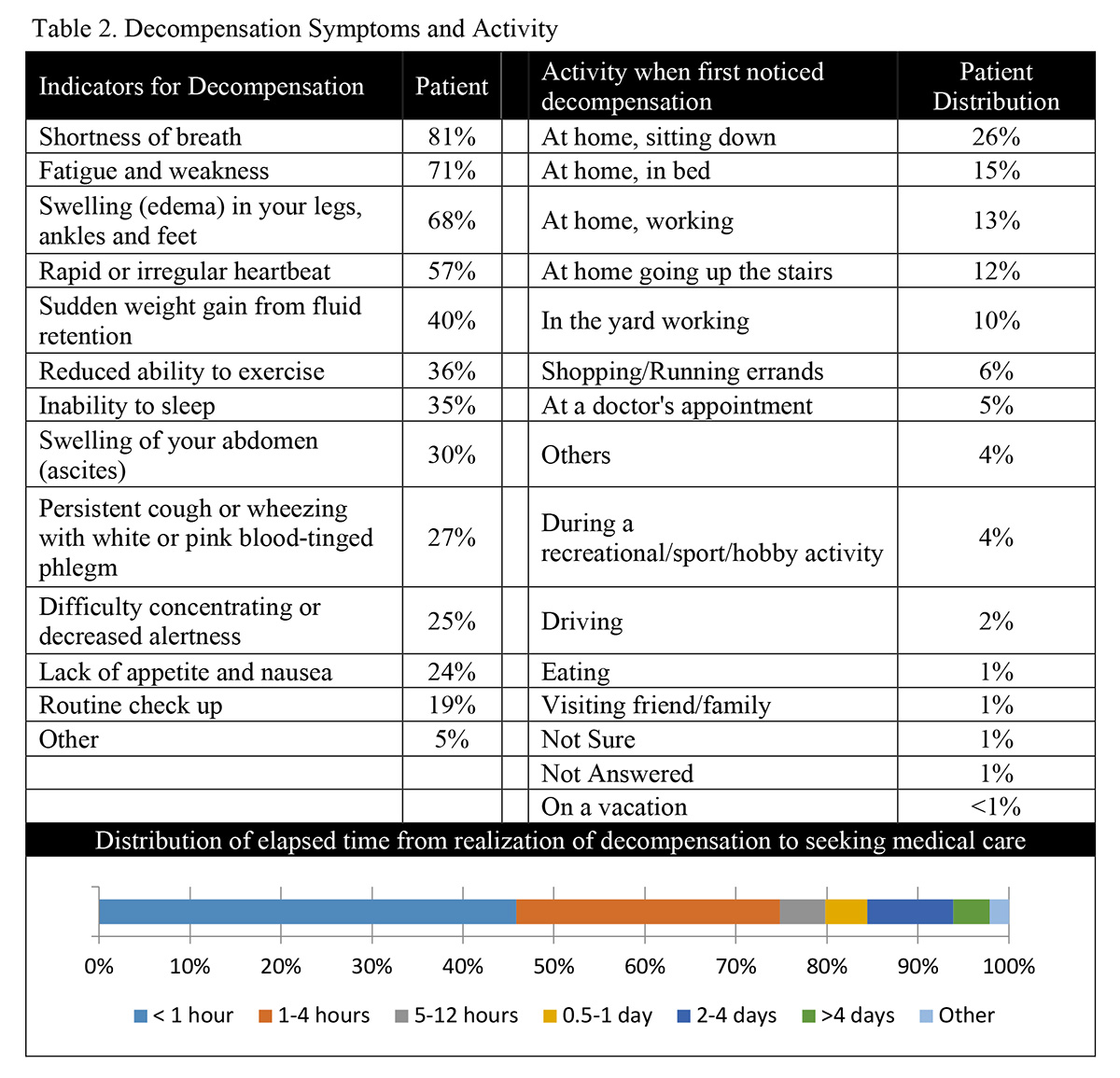

The most frequently (>50%) reported symptoms indicating decompensation included "shortness of breath" (81%), "fatigue and weakness" (71%), "swelling in legs, ankles, and feet" (68%), and "rapid and irregular heart beat" (57%). Location of respondents when they first noticed decompensation was sitting at home (26%), in bed at home (16%), working at home (13%), going up the stairs at home (12%), working in the yard (10%), "shopping/running errands" (6%), and "at a doctor's appointment" (4%). The majority (79%) sought help within 12 hours of the onset of decompensation with nearly half (46%) seeking help within the first hour. There was greater delay (>12 hours) in seeking treatment by respondents who had no previous HF hospitalization compared to those with prior hospitalization (35% vs. 14%, p<0.001). Being driven by a family member (45%) was the primary mode of transportation used to reach the hospital followed by ambulance (26%) or driving themselves (11%). Fourteen percent waited longer than 2-days to seek help. A minority of respondents (19%) discovered decompensation symptoms during routinely scheduled evaluation by a clinician. It could not be determined from the questionnaire if these patients failed to recognize their symptoms earlier or recognized them but waited to discuss symptoms with a clinician. (Table 2).

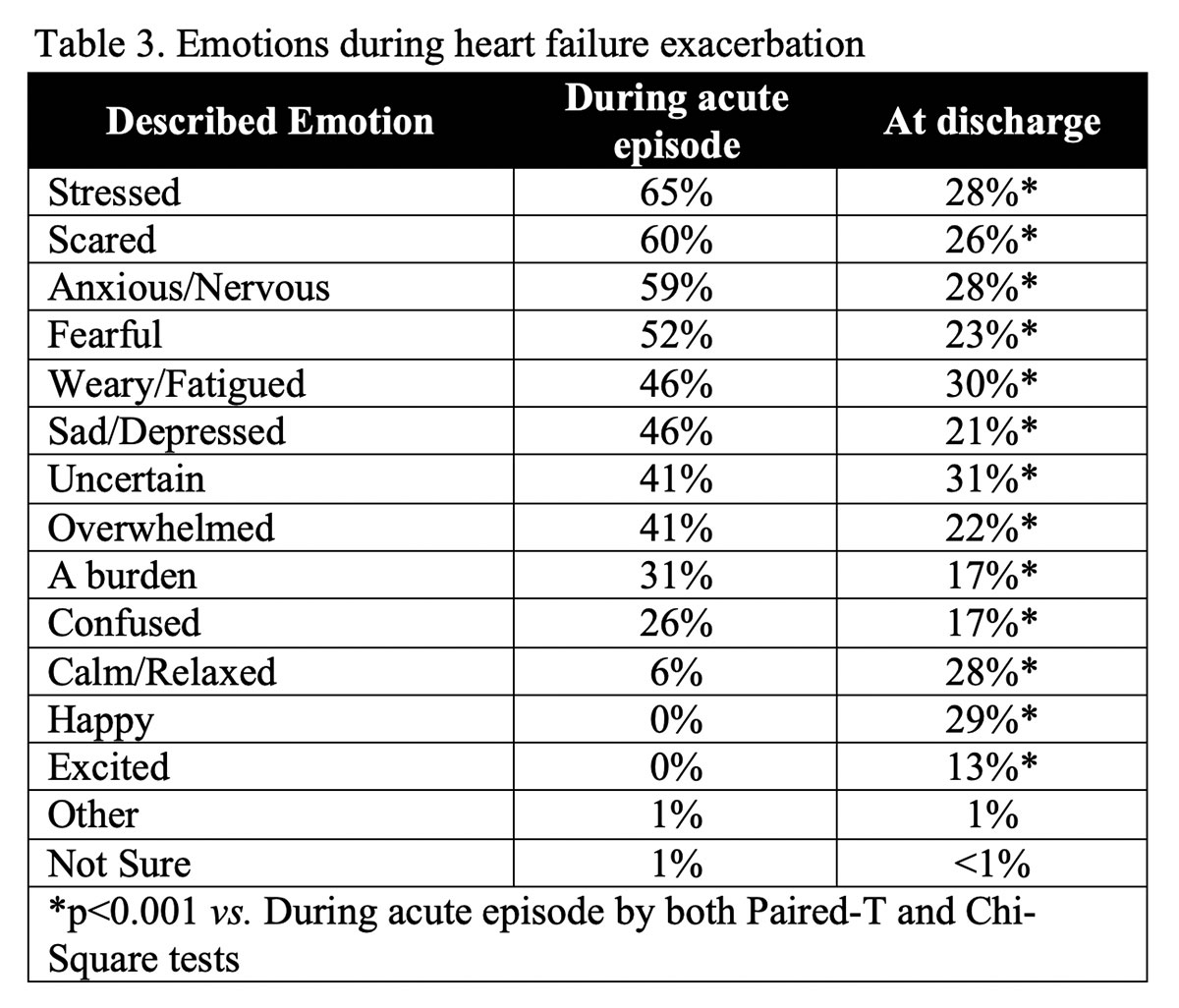

Upon recognition of HF decompensation, a majority of respondents felt "stressed" (65%), "scared" (60%), "anxious/nervous" (59%), and "fearful" (52%) (Table 3).

Respondents reported feeling better at discharge with decreasing emotions of "stressed" (28%), "scared" (26%), "anxious/nervous" (28%), and "fearful" (23%) with p<0.001 (by both paired-t and chi-square tests; see Table 3 for all).

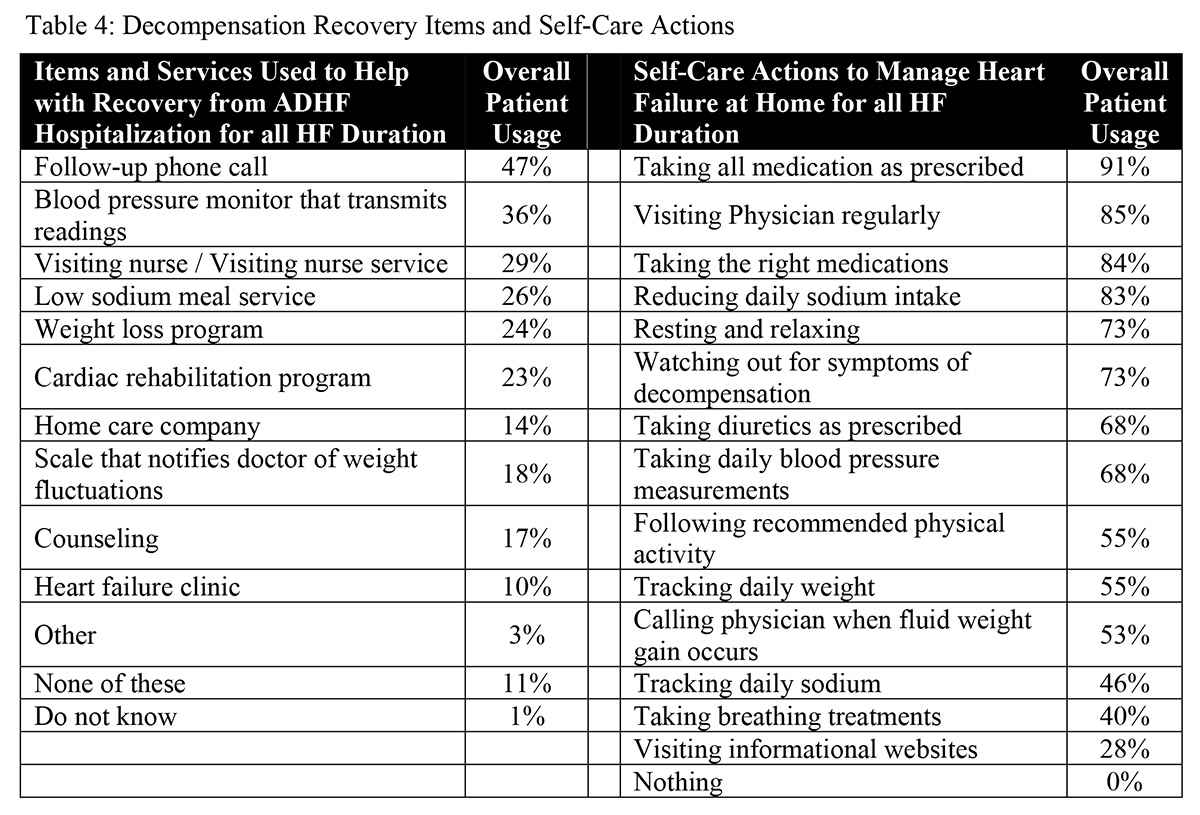

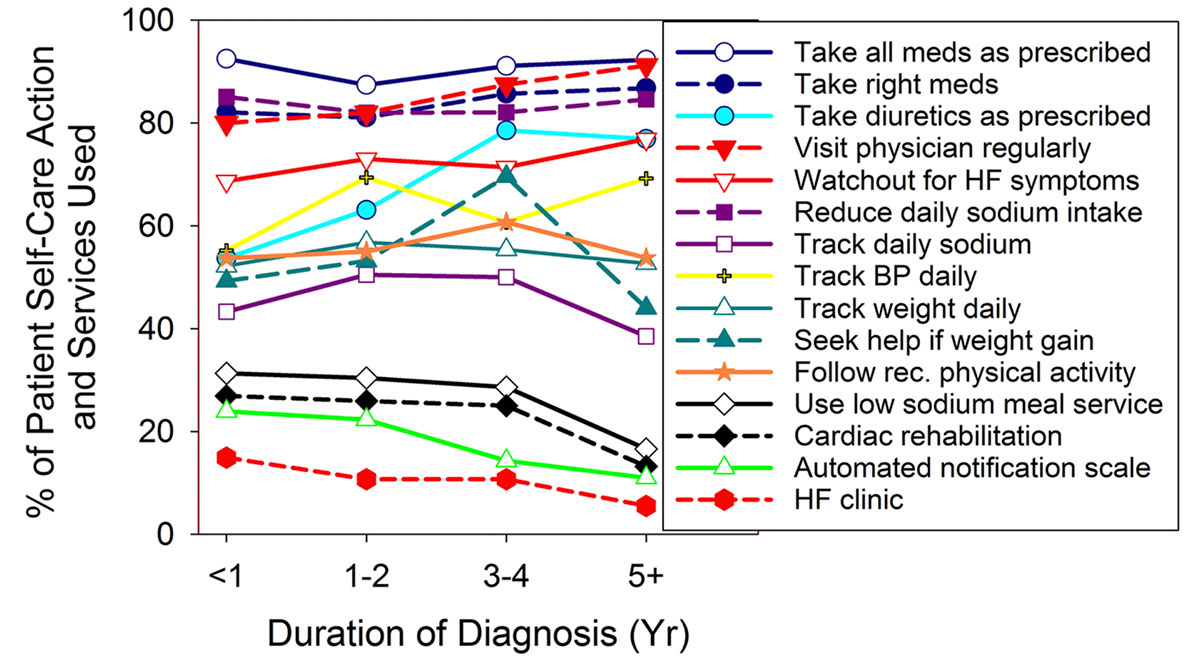

The majority of respondents reported "taking all medications as prescribed," and "taking the right medication" (see Figure 3). The percentage reporting these actions remained unchanged regardless of HF duration. Respondents reported "cutting down on sodium" consistently at 83% overall. However, respondents also reported tracking sodium intake to a variable extent over time since diagnosis, starting at 43% (<1 year), increasing to 51% (1-2 years), and decreasing to 39% (>5 years). Adherence to prescribed diuretics started at 54%, increased with HF duration to peak of 79% (3-4 years), but dropped off slightly 77% at HF duration >5 years. Watching for worsening HF symptoms undulated but trended positively with HF duration reaching 77% with HF duration >5 years. Tracking daily weight held steady at 54% regardless of disease duration. Seeking help for fluid weight gain increased from 49% (< 1 year) to 70% (3-4 years); however, this action dropped to 44% at HF duration >5 years. We performed correlation analysis on reported self-care actions to HF duration and found that "visit physician regularly" positively correlated with HF duration (80% at <1 year to 91% at >5 years, r=0.997, p=0.003). Other self-care actions did not achieve statistical significance in correlation with HF duration.

We analyzed responses to determine whether conditional associations of symptom recognition, self-care monitoring, and seeking timely medical intervention exist. A majority (59%) who reported "sudden weight gain from fluid retention" also tracked daily weight. 71% who tracked daily weight also sought. Among all who reported "sudden weight gain from fluid retention", those who tracked daily weight were more likely to seek help with fluid weight gain than those who do not track daily weight (71% vs. 39%, p<0.001).

Correlation analyses were performed to ascertain association between remembered written hospital discharge instructions and reported patient self-care actions. In general, large scatter existed among remembered instructions and reported self-care actions (Figure 4).

Reported action of "taking all medication as prescribed" only show weak unadjusted correlation with remembered discharge instruction of "being diligent about taking all medication as prescribed" (r=0.135 and unadjusted p=0.014). Adjusting for multiple comparisons made this correlation non-significant (the unadjusted p needed to be ≤0.003571 to account for multiple comparisons). Self-care actions that showed moderate correlation with remembered instructions included taking blood pressure daily (r=0.474, p<0.000001), tracking sodium daily (r=0.326, p<0.000001), taking diuretics as prescribed (r=0.320, p<0.000001), and tracking daily weight (r=0.291, p<0.000001). The remembered instruction of "following up with your doctor within a week of your discharge" correlated with the highest number of reported self-care actions (Figure 3).

In addition to self-care actions, the survey also examined use of commonly provided services (Table 4). Respondents most commonly reported: "follow-up phone call" (47%); "blood pressure monitor that transmits readings" (36%); "visiting nurse /visiting nurse service" (29%); and "low sodium meal service" (26%).

Discussion

Our study adds to the literature on patient experience by reflecting the HF patient journey both before and after hospitalization by exploring areas that were not in previous smaller self-care studies.14,15 These findings demonstrated which remembered discharge instructions were associated with performance of self-care actions and provide evidence that performance of self-monitoring can lead to seeking medical help. These findings are new even among the recently completed large systematic reviews.16,17

The women HF patients in this study were socio-economically disadvantaged. These results are consistent with a large study that show socio-economic deprivation increases risk of HF among women18. Since living alone19 and lower income20 can increase mortality, then, an effective PCC program for HF care will need to address these issues.

The survey responses shed light on the acuity of symptoms at the time of onset, as well as the fear experienced. The change in symptoms reported at the time of hospital discharge is encouraging and very important given health policy implications of patient reported outcomes and patient experience.9,21,22

Previous studies suggested that increasing HF duration improves performance of self-care actions14,15. In our study, with the exception of visit physician regularly, percentages of respondents performing self-care actions did not consistently improve and performance of some self-care actions worsened with duration of HF. (Figure 2) Larger sampling size (~3 fold), greater participation of women respondents (46% vs. ≤17-26%), and inclusion of HF duration >3 years may have resulted in these differences.14,15 The lack of improvement with HF duration underscores the importance of continuous education and encouragement to perform self-care actions as a part of PCC.

A majority (79%) expressed confidence in recognition of HF decompensation and the intention to seek care in a timely manner. Confidence has been demonstrated to contribute to better self-care15,23. The strong positive finding that respondents who track daily weight will seek help for fluid weight gain demonstrated that respondents can translate self-monitoring into action. As weight gain predicts hospital admission24, this translation of self-monitoring to action is important. Positive correlation of self-care actions to instructions demonstrated that respondents are willing to perform self-care actions. Thus, the combination of confidence in recognition of HF decompensation, seeking help in timely fashion, translation of self-monitoring to action, and willingness other evidence of self-efficacy demonstrated potential to improve self-care performance among HF patients.

Study results emphasize the necessary components for an effective PCC HF program. Recognition of the patient experience is crucial. A program needs to nurture patients' capacity for self-care and self-efficacy. Sustained training with follow-up coaching can grow the identified potential into significant improvements in self-care.16,25 As suggested by interaction of self-care and depression in a systematic review17, improvements gained from better self-care may lead to less depression, thereby further increasing effectiveness. Since patient self-care can provide timely if not immediate intervention, improved self-care may succeed where interventions that rely on technologies and external instructions, which can be delayed by days, have not made significant differences.26-28

Limitations

The online method of recruitment for this study likely contributed to the relatively small number of qualified respondents (331) in comparison to the large size of total respondents (14,720). Recruitment of patients from hospital systems and/or cardiovascular practices would likely have increased the sample size dramatically. Patient recall may well have been improved had subjects been recruited from the acute care setting. Many older patients may not have had easy access or to be regular users of internet; therefore, the internet-based survey may have been another limiting factor. Furthermore, the conduction of the survey relied on consumer panels. These panels may have missed significant portions of HF patients.

Conclusions

Patient experience and patient reported outcomes are achieving greater prominence in the age of the transition from volume to value in healthcare. To fill this need, the ACC conducted a national survey of ADHF patients to document their journey using internet based commercial panels. The results showed that: A) patients expressed confidence in identifying decompensation, B) patients who experienced at least one HF admission will seek care promptly with decompensation,(C) women with HF are socio-economically disadvantaged, D) performance of self-care actions did not improve with duration of HF, and E) patients can perform self-care actions if instructed. Therefore, improving performance of self-care actions and providing social-economic assistance hold potential of providing effective patient centered care that improves outcome and patient satisfaction.

Acknowledgement

Novartis provided funding for the survey. Data collection, data analyses, manuscript composition, and publication submission were completely independent of Novartis. NIH/NHLBI K08HL114877 supported CT. The authors report they do not have relationship with industries.

References

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:e38-e360.

- Braunwald E. The war against heart failure. Lancet 2015;385:812-24.

- Forouzanfar MH, Moran A, Phillips D, et al. Prevalence of Heart failure by cause in 21 regions: global burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors-2010 study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:E786.

- Ni H, Xu J. Recent Trends in heart failure-related mortality: United States, 2000-2014. In: HHS, editor: CDC-NCHS Data Brief No. 231, 2015:1.

- Spertus JA. Evolving applications for patient-centered health status measures. Circulation 2008;118:2103-10.

- Riegel B, Moser DK, Anker SD, et al. State of the science: promoting self-care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009;120:1141-63.

- Ruppar TM, Cooper PS, Mehr DR, Delgado JM, Dunbar-Jacob JM. Medication Adherence interventions improve heart failure mortality and readmission rates: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5.

- Dunbar SB, Reilly CM, Gary R, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an integrated self-care intervention for persons with heart failure and diabetes: quality of life and physical functioning outcomes. J Card Fail 2015;21:719-29.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21 Centruy, Brief and Full Reports. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine, 2001. 10. Ulin K, Malm D, Nygardh A. What is known about the benefits of patient-centered care in patients with heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2015.

- Bekelman DB, Plomondon ME, Carey EP, et al. Primary results of the patient-centered disease management (PCDM) for heart failure study: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:725-32.

- Ekman I, Wolf A, Olsson LE, et al. Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: the PCC-HF study. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1112-9.

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and poverty in the United States: 2014. In: Commerce, editor. Current Population Reports, P60-252 ed. Washington DC: United States Census Bureau, 2015.

- Carlson B, Riegel B, Moser DK. Self-care abilities of patients with heart failure. Heart Lung 2001;30:351-9.

- Ni H, Nauman D, Burgess D, Wise K, Crispell K, Hershberger RE. Factors influencing knowledge of and adherence to self-care among patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1613-9.

- Clark AM, Wiens KS, Banner D, et al. A systematic review of the main mechanisms of heart failure disease management interventions. Heart 2016;102:707-11.

- Kessing D, Denollet J, Widdershoven J, Kupper N. Psychological determinants of heart failure self-care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2016;78:412-31.

- Pujades-Rodriguez M, Timmis A, Stogiannis D, et al. Socioeconomic deprivation and the incidence of 12 cardiovascular diseases in 1.9 million women and men: implications for risk prediction and prevention. PLoS One 2014;9:e104671.

- Huynh QL, Saito M, Blizzard CL, et al. Roles of nonclinical and clinical data in prediction of 30-day rehospitalization or death among heart failure patients. J Card Fail 2015;21:374-81.

- Eapen ZJ, McCoy LA, Fonarow GC, et al. Utility of socioeconomic status in predicting 30-day outcomes after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:473-80.

- Bonow RO, Ganiats TG, Beam CT, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 performance measures for adults with heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the American Medical Association-Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. Circulation 2012;125:2382-401.

- Kelkar AA, Spertus J, Pang P, et al. Utility of patient-reported outcome instruments in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:165-75.

- Heo S, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Riegel B, Chung ML. Gender differences in and factors related to self-care behaviors: a cross-sectional, correlational study of patients with heart failure. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:1807-15.

- Chaudhry SI, Wang Y, Concato J, Gill TM, Krumholz HM. Patterns of weight change preceding hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 2007;116:1549-54.

- Granger BB, Ekman I, Hernandez AF, et al. Results of the chronic heart failure intervention to improve medication adherence study: a randomized intervention in high-risk patients. Am Heart J 2015;169:539-48.

- Chaudhry SI, Mattera JA, Curtis JP, et al. Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2301-9.

- Lynga P, Persson H, Hagg-Martinell, A et al. Weight monitoring in patients with severe heart failure (WISH). A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:438-44.

- Ong MK, Romano PS, Edgington S et al. Effectiveness of remote patient monitoring after discharge of hospitalized patients with heart failure: the better effectiveness after transition-heart failure (BEAT-HF) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:310-8.

- Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998-2008. JAMA 2011;306:1669-78.

Clinical Topics: Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Self Care, Medication Adherence, Patient Discharge, Diuretics, Ambulances, Body Weight, Weight Gain, Hospitalization, Heart Failure, Fatigue, Anxiety

< Back to Listings