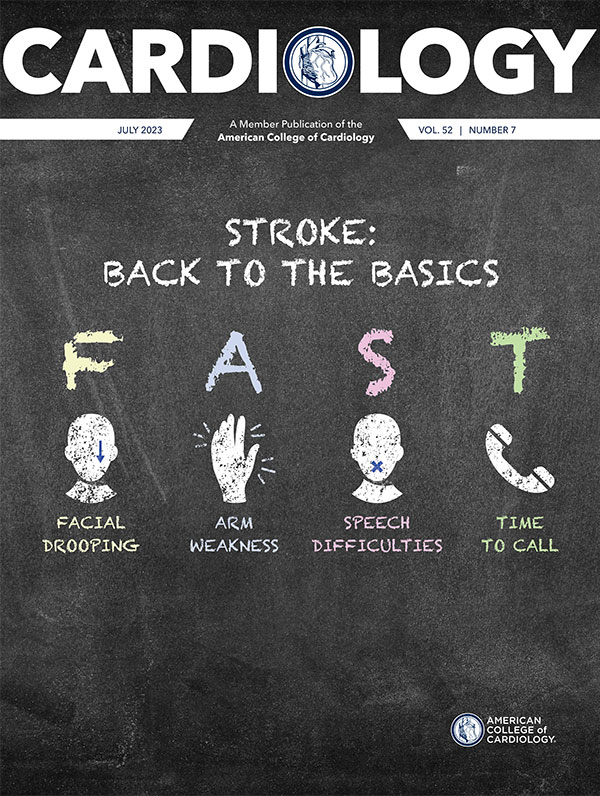

Cover Story | Stroke: Back to the Basics

Up to 80% of strokes may be preventable. That's a weighty statistic for an event that is the primary cause of serious long-term disability, ranks in the U.S. as the fourth and fifth leading cause of death among men and women, respectively, and is the second leading cause of deaths globally, following ischemic heart disease.

This month's cover story reviews some basics about stroke, including the importance of hypertension as a risk factor, and looks at some of what's new in the world of stroke care.

Stroke Trends

Each year about 795,000 people in the U.S. have a first (about 610,000) or recurrent (about 185,000) stroke.1 For comparison, it's estimated that about 805,000 people in the U.S. have a myocardial infarction (MI) annually, 605,000 of which are first MIs.1 But the crude incidence of stroke fails to capture the true extent of disability resulting from this condition.

"Even though the numbers are similar, the chance of severe disability after stroke is so much greater, even with the advances we've made in hyperacute treatment of stroke with thrombolytics and mechanical thrombectomy," says Kristin Miller, MD, a stroke neurologist at the University of Michigan.

About 7.8 million adults in the U.S. have experienced a stroke during their lifetime. Among individuals aged 65 years or older who survive a stroke, approximately half experience reduced mobility. The American Stroke Association estimates that the economic burden associated with stroke in the U.S. amounts to (conservatively) about $46 billion annually.

About 87% of all strokes are ischemic, a heterogenous condition characterized by reduced or obstructed arterial blood flow to the brain (which includes the retina and the spinal cord). This type of stroke is more likely to be caused by cardiac issues, such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation (AFib) or valvular heart disease.

– Kristin Miller, MD

The term cryptogenic stroke, also called ischemic stroke of unknown origin or embolic stroke of undetermined source, refers to ischemic strokes for which no probable cause is identified despite a thorough diagnostic evaluation. They can be embolic or nonembolic.

Hemorrhagic strokes, on the other hand, are caused by bleeding in the brain, usually due to a ruptured blood vessel. While cardiac issues can sometimes contribute to the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, they are not typically the primary cause. There are data showing that a high proportion of hemorrhagic strokes, relative to ischemic stroke, are seen in low- and middle-income countries, where the burden of hypertension is greater.2

Although far less common than ischemic stroke, mortality associated with acute hemorrhagic stroke is much higher (40-45% vs. 15% for ischemic stroke).

Regardless of subtype, there has been a long-term decrease in the incidence of stroke in the U.S. and elsewhere.3,4 However, much of this decrease has been in older adults while stroke incidence in midlife appears to be plateauing or slightly increasing in the U.S., likely attributed to increasing incidence of obesity, its impact on early diabetes, and substance abuse disorder.1

Gender Differences

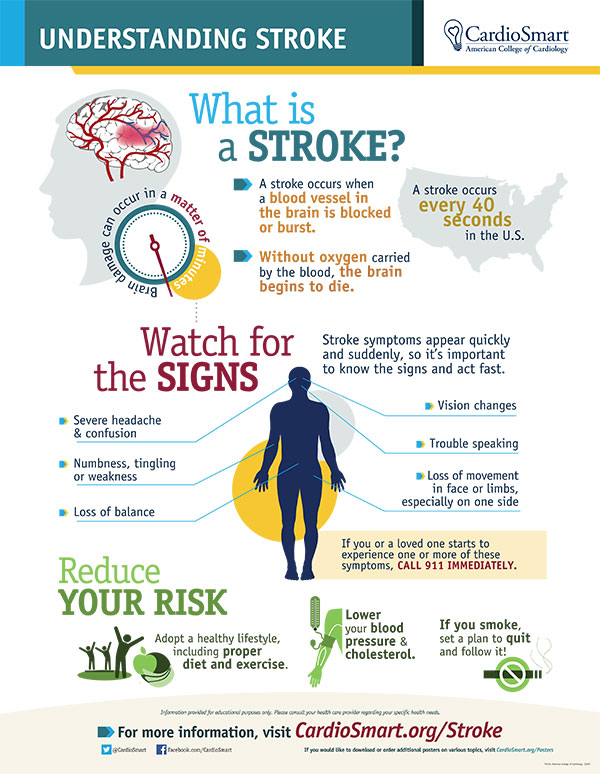

Equipping Our Patients

Help patients understand their risk of stroke, the signs and symptoms and what to do. Click here to download the CardioSmart infographic and don't forget to teach the basics: F-A-S-T.

Men have a higher age-adjusted incidence of stroke compared with women, but more women than men die from stroke every year, which is largely attributed to their longer life expectancy. What is largely underappreciated, however, is that women tend to have worse outcomes, greater disability, and a greater decrease in quality of life after a stroke compared with men.6

Also all but ignored are some sex-specific differences in stroke risk. "Paying better attention to women who have not yet had a stroke, and particularly people of different races and ethnicities, understanding they have a higher risk for stroke and worse outcomes after stroke might make a big difference in reducing the overall burden of stroke and stroke-related disability," says Miller.

Pregnancy itself increases stroke risk, both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, particularly in the peripartum period (two days before to one day after birth). Much, but not all, of this excess risk is associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

The risk doesn't end there. In a meta-analysis published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, exposure to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, was also associated with a significantly increased risk for any stroke and ischemic stroke among parous patients in later life.7 Preeclampsia impacts up to 8% of American women and its incidence is increasing. Hypertension in pregnancy is seen in about 15% of women.

In a study just published in Neurology, a group from South Korea looked at why women might have worse outcomes after stroke compared with men.8 They analyzed data from MRI scans of almost 6,500 patients with recent ischemic stroke to see how the stroke affected different parts of the brain.

The results showed that while percentage infarct volumes were similar between women and men, women had more severe strokes, as indicated by higher stroke severity scores. They also experienced more frequent deterioration in their neurological condition within the first three weeks after the stroke.

Women were more likely to have damage in certain parts of the brain, specifically the striatocapsular region, and less likely to have damage in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum. This was consistent with angiographic findings, which showed that women had more narrowing in the middle cerebral artery, while men had more blockages in the internal carotid artery and vertebral artery.

Interestingly, the study found that women with left-sided parieto-occipital cortical infarcts had more severe symptoms compared with men with similar amounts of damage to the same region. As a result, women were less likely to achieve functional independence three months after the stroke compared with men.

Says Martin, "Not only are women more likely to suffer a stroke in their lifetime and have a higher rate of death from stroke compared with men, but it also seems as though certain risk factors affect women's stroke risk more than men, including diabetes and hypertension, which is even more reason to pay attention to modifiable risk factors in women for primary prevention as well as secondary prevention of stroke."

Hypertension Remains #1 Risk Factor

Atherothrombosis is the most important mechanism of ischemic stroke and hypertension is the most important cause. Hence while lipid lowering offers the greatest bang for the buck in prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, hypertension is its corollary for stroke prevention.

The suggestion that risk factors for heart disease and peripheral artery disease mirror those for stroke is technically correct, but not entirely precise, suggests Mitchell Elkind, MD, MS, MPhil, chief clinical science officer of the American Heart Association and former head of the division of Neurology Clinical Outcomes Research and Population Sciences (Neuro CORPS) at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

"It's not so much a difference in kind as in emphasis, because although heart disease and stroke share many risk factors, their relative importance differs a bit. Cholesterol tends to be particularly important for heart disease, but a little bit less important as a cause of stroke," says Elkind. While about 95% of heart attacks are due to large vessel atherosclerosis, it accounts for only 20% of ischemic stroke etiologies.

Measure Well

Click here for an ACC.org Expert Analysis on best practices for measuring BP accurately and the impact (in mm Hg) of common measurement pitfalls.

"Conversely, hypertension is the most important modifiable risk factor for stroke, with a strong, direct, linear and continuous relationship between blood pressure and stroke," he adds.

"Hypertension causes about 50% of strokes overall, and perhaps as many as 80% of hemorrhagic strokes, so we tend to be particularly aggressive in controlling high blood pressure in both primary and secondary prevention."

In INTERSTROKE, a global, case-controlled study that included 26,919 participants from 32 countries, hypertension was by far the most important stroke risk factor. Using a definition that included both a history of hypertension and a blood pressure measurement of 160/90 mm Hg, the population attributable risk (the proportion of stroke in the population that was attributable to hypertension) was 54%.9

Overall, the study, the largest and most comprehensive international study on the topic, found that the top 10 risk factors for stroke accounted for 90.7% of the population attributable risk of stroke, implying that if these risk factors were eliminated, 90.7% of all strokes could be prevented.10

Lowering systolic blood pressure by 10 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure by 5 mm Hg reduces the risk of stroke by 40%.11 Lower is better also appears to apply to those considered to be "normotensive" and even down to 110 mm Hg systolic and 60 mm Hg diastolic.

Mechanical thrombectomy became the gold-standard treatment for ischemic stroke caused by large-vessel occlusions (LVO) in 2015 after five clinical trials demonstrated its efficacy and safety compared with standard care. Since then, stroke care has largely centered around improving access to and expanding patient eligibility for thrombectomy.14

Mobile stroke units (MSUs) are designed to provide prehospital care to stroke patients, with the goal of providing ultra-early thrombolysis to better preserve brain tissue. First launched in Germany in 2010 and in the U.S. in 2014, MSUs are comprised of some combination of paramedics and EMTs, along with a radiation technologist and a dedicated neurologist, either on board or via telehealth.

Two pivotal trials published in 2021, B_PROUD and BEST-MSU, demonstrated that as compared with conventional EMS care, treatment aboard MSUs was safe and led to faster administration of tPA, improved functional outcomes, and less disability in patients with acute stroke.15,16

"The concept is straightforward: If you bring a CT scanner into the field and see the patient has a thrombotic stroke, you can give tPA right away. If it's hemorrhagic, obviously you hold the tPA and get them to the OR as quickly as possible," says Joshua D. Hartman, MBA, NRP (Nationally Registered Paramedic).

Hartman has been a critical care paramedic for more than 25 years in both New York City and northern New Jersey and is senior vice president, Cardiovascular, Emergency and Mobile Medicine divisions at HMP Global, a provider of health care events and education.

One recent study looked at whether a machine learning algorithm was able to accurately and rapidly detect LVOs using prehospital CTA acquisitions. The algorithm needed less than a minute to assess the scan and performed well in identifying LVOs, with an area under the receiver-operator curve of 0.84 (95% CI, 0.80-0.87).17

MSUs are expensive to set up and staff, however, and they are currently not reimbursed by insurers. Most initial funding for these programs came from foundations and grants and much of that funding has since dried up. Cost-effectiveness analyses of MSUs are currently underway.

"Today there are still mobile stroke units on the road, but fewer than even two or three years ago, at least here in the New York City area," says Hartman, who is currently a tour chief and paramedic at Englewood Health in Englewood, NJ.

Now, Hartman adds, the focus for all EMS units is on getting stroke patients as quickly as possible to a thrombectomy-capable or comprehensive stroke center, where they can receive both a CT scan and, if indicated, thrombectomy.

"Just as with STEMIs, where we want to get our patient to a PCI-capable hospital quickly, these days for a stroke patient that meet certain criteria – which have been expanded – we might bypass a primary stroke center that can provide tPA in 10 or 15 minutes and instead go directly to a comprehensive stroke center so they can get thrombectomy on their first trip, says Hartman."

Indeed, the AHA/ASA's Mission Lifeline algorithm for prehospital stroke triage recommends direct transport to a thrombectomy-capable stroke center instead of a primary stroke center or acute stroke ready hospital if the transport time is <30 minutes.

In a comprehensive survey published in 2022, among 5,533 U.S. emergency departments, 2,446 (44%) were stroke centers, including (from most to least advanced) 297 comprehensive stroke centers, 14 thrombectomy‐capable stroke centers, 1,459 primary stroke centers, and 678 acute stroke ready hospitals.18

It should be noted, says Brijesh P. Mehta, MD, that the subset of stroke centers that is certified by accreditation bodies such as the Joint Commission is relatively small compared with the total number of stroke centers.

"The availability of endovascular thrombectomy for LVO strokes is not limited to nationally-certified stroke centers. Specifically in the Midwest and rural areas that have far fewer certified stroke centers compared with urban regions, thrombectomy is being performed at local stroke centers, albeit at lower rates," says Mehta, a neurointerventional surgeon and medical director of of the Comprehensive Stroke Program and NeuroInterventional Surgery at the Memorial Neuroscience Institute in Hollywood, FL.

"This provides a major opportunity for improving prehospital stroke protocols and systems of care to ensure patients with LVOs are identified promptly by paramedics and transported to the most appropriate stroke centers."

One question still being examined is whether, after 20 years as the only treatment option in acute ischemic stroke, thrombolysis is still necessary (and beneficial) in patients in whom thrombectomy is indicated. Several studies have looked at this and the evidence to date suggests that thrombolysis remains warranted in eligible patients.1

Not Always "Silent"

There is a growing recognition that hypertension, long called the "silent killer" due to its ability to go undetected, can sometimes in fact be fairly noisy, particularly in women.

According to Angela Maas, MD, emeritus director of the Women's Cardiac Health Programme, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, women are more likely than men to experience symptoms of hypertension, but they may be mistaken for menopause, anxiety or stress.

Says Maas, young and middle-aged women with high blood pressure often report palpitations and tachycardia (even paroxysmal AFib), tight, nagging and often continuous chest pain at rest, pain between the shoulder blades, headaches, difficulty concentrating, shortness of breath, tiredness, fluid retention, poor sleep, hot flashes and a feeling that their bra is too tight.

"When we treat hypertension, many symptoms erroneously attributed to menopause disappear," said Maas in a recent European Society of Cardiology press release. "Night sweats can be caused by high blood pressure, for example, so women with menopausal symptoms should have their blood pressure checked and treated, if needed."

Also, recent data suggest that the risk for cerebrovascular complications starts at lower blood pressure levels in women than in men, suggesting that sex-specific blood pressure-lowering guidelines may be important. However, due to gaps in the evidence base and a lack of trials designed specifically to better understand these sex differences, it is unclear at present whether (or how) hypertension should be managed differently in women and men, including treatment goals and choice and dosages of antihypertensives.12

Blacks have the highest rate of death due to stroke among all racial and ethnic groups and stroke is a leading cause of death among Black women, almost three in five of whom are diagnosed with hypertension.

The disproportionately higher burden of hypertension and diabetes among African American women is likely a driver of their higher rates of stroke. Blacks are also less likely to have their blood pressure controlled and more likely to have blood pressure variability. Blood pressure variability is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, including stroke.13

For Hispanic women, stroke is the fourth leading cause of death, more than half of whom have obesity and more than one in three of whom have elevated blood pressure. As well, diabetes is highly prevalent among adults of Hispanic origin, particularly those of Mexican and Puerto Rican ancestry.

"Overall, death rates from stroke have been declining, but this fall does not seem to be happening in Black and Hispanic populations, or in women, so this is something we need to understand better and find better solutions," says Miller.

Which Came First: The AFib or The Stroke?

In the 30% of patients for whom no clear origin or cause of stroke can be determined, AFib is considered a potential culprit.

"If someone comes in with an ischemic stroke and there is new detection of AFib at the time of their stroke, we usually feel pretty confident saying the AFib was the cause of the stroke," says Elkind.

Stroke strikes some groups harder than others, with the risk varying by race, ethnicity and age.

Non-Hispanic Black adults have the highest risk – two-fold higher than White adults. And they, along with Pacific Islanders, have the highest rates of death from stroke.

Among Black women, stroke is the leading cause of death, increasing the need to ramp up efforts to better diagnose and control blood pressure.

Stroke is the #4 cause of death among Hispanic women, a group with a high rate of obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes. It hits at any age – but the incidence of stroke is increasing in middle-age adults.

Geography also matters. The Southeastern region of the U.S. continues to see higher rates of stroke and deaths from stroke.

Obviously, defining the etiology of stroke is key to secondary prevention of recurrent stroke and in this, there is a role for "aggressive cardiac evaluation with a heavy emphasis on managing risk factors, including modifying diet, increasing physical activity, and using an evidence-based approach," he adds.

But the determination of cryptogenic stroke is a game of semantics to some extent. "Some clinicians will say that if someone has an unexplained stroke and they are found to have, say, a patent foramen ovale (PFO), then the PFO was the cause of the stroke and it's no longer cryptogenic," says Elkind. "But the issue in such a case is that we're making an assumption that the PFO caused the stroke, which might be right or it might not be."

Something similar occurs with AFib. With aging, people are more likely to develop small lacunar strokes deep in the brain, which are usually attributed to a blockage and not due to an embolism from the heart, which typically blocks off a larger blood vessel. "But as people age and accumulate risk factors over time, the risk of AFib also rises. So in truth we could be seeing both of those things – AFib and a small stroke, but they're not actually related," says Elkind.

"Indeed, recent studies using long-term cardiac monitoring have demonstrated that the weight of detection of AFib is as high in people who have those small lacunar strokes where we don't think it's an embolism, but it in fact is," he adds. "This is surprising, but what it really tells us is that our ability to distinguish or determine the cause of a stroke in any individual person is limited."

There is also a chicken and an egg conundrum. When AFib is detected after an ischemic stroke for which there is no clear cause, it often becomes the presumed cause of the stroke.

"Paroxysmal AFib is an important cause of stroke, but sometimes we might not detect any AFib during hospitalization or even for months after," says Elkind. "Also, in studies of cardiac patients implanted with monitoring devices, only about a quarter of patients were in AFib in the 30 days prior to the stroke."

This has led him and others to hypothesize that fibrosis and other acquired abnormalities of the left atrium, even in the absence of AFib, may provide a milieu for thrombus formation by promoting stasis, endothelial dysfunction and hypercoagulability. They've called this condition atrial cardiopathy.

The ongoing ARCADIA (Atrial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs in Prevention after Cryptogenic Stroke) trial is comparing apixaban to aspirin in secondary stroke prevention in cryptogenic stroke and atrial cardiopathy, based on thresholds of P-wave terminal force, NT-proBNP or left atrial diameter, all of which are proposed biomarkers of atrial cardiopathy. Results are expected in June 2024.

"The other question is whether people who have AFib detected after they have a stroke are at the same increased risk as people who have it beforehand. There's increasing evidence to suggest that they're not at the same risk," says Elkind.

"So, detecting AFib after somebody has a stroke may represent a lower-risk form of AFib, and in some people it may be that the damage to the brain actually leads to the AFib rather than the other way around."

– Kristin Miller, MD

Damage to the insula, for example, a medial part of the brain that controls autonomic function and is responsible for parasympathetic and sympathetic tone, is associated with an increased risk of AFib and other heart rhythm abnormalities.

Regardless of whether AFib precedes stroke or is a result of it, what is abundantly clear is that the greatest bang for the buck in terms of stroke reduction across the population is better hypertension control. Says Vaduganathan, et al., in a JACC article summarizing the most recent data from the 2022 Global Burden of Disease study: "High systolic blood pressure remains the leading modifiable risk factor globally for attributable premature cardiovascular deaths…and has been particularly linked to ischemic heart disease and stroke-related deaths."5

Simplification of strategies of blood pressure control (e.g., combination drug products), public health measures (e.g., salt substitutes and salt reduction in processed foods), and community-based measures (e.g., pharmacist-led management and health promotion at barbershops and beauty salons) are all needed to tackle the scourge of hypertension-related CVD stroke, they add.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147:e93-e621.

- Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MSV. Stroke risk factors, genetics, and prevention. Circ Res 2017;120:472-95.

- Aparicio HJ, Himali JJ, Satizabal CL, et al. Temporal trends in ischemic stroke incidence in younger adults in the framingham study. Stroke 2019;50:1558-60.

- Lisabeth LD, Brown DL, Zahuranec DB, et al. Temporal trends in ischemic stroke rates by ethnicity, sex, and age (2000-2017): The brain attack surveillance in corpus christi project. Neurology 2021;97):e2164-e2172.

- Vaduganathan M, Mensah GA, Turco JV, Fuster V, Roth GA. The global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:2361-71.

- Bushnell CD, Chaturvedi S, Gage KR, et al. Sex differences in stroke: Challenges and opportunities. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018;38:2179-91.

- Brohan MP, Daly FP, Kelly L, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and long-term risk of maternal stroke-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;Mar 27:S0002-9378(23)00197-7.

- Ryu WS, Chung J, Schellingerhout D, et al. Biological mechanism of sex difference in stroke manifestation and outcomes. Neurology 2023;Jun 13:100(24):e2490-e2503.

- O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet 2010;376:112-23.

- O'Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, et al. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet 2016;388:761-75.

- Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ 2009;338:b1665.

- Gerdts E, Sudano I, Brouwers S, et al. Sex differences in arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2022;43:4777-88.

- Stevens SL, Wood S, Koshiaris C, et al. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;354:i4098.

- Pajor MJ, Adeoye OM. Evolving stroke systems of care: Stroke diagnosis and treatment in the post-thrombectomy era. Neurotherapeutics 2023;20:655-63.

- Ebinger M, Siegerink B, Kunz A, et al. Association between dispatch of mobile stroke units and functional outcomes among patients with acute ischemic stroke in berlin. JAMA 2021;325:454-66.

- Grotta JC, Yamal JM, Parker SA, et al. Prospective, multicenter, controlled trial of mobile stroke units. N Engl J Med 2021;385:971-81.

- Czap AL, Bahr-Hosseini M, Singh N, et al. Machine learning automated detection of large vessel occlusion from mobile stroke unit computed tomography angiography. Stroke 2022;53:1651-6.

- Boggs KM, Vogel BT, Zachrison KS, et al. An inventory of stroke centers in the United States. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2022;3(2):e12673.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Prevention, Valvular Heart Disease, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Hypertension

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Ischemic Stroke, Atrial Fibrillation, Cardiovascular Diseases, Embolic Stroke, Neurologists, Hemorrhage, Brain, Embolism, Heart Valve Diseases, Thrombectomy, Hypertension, Infarction

< Back to Listings