Feature | TAVR: Clearing Hurdles to Become an Established Treatment

As he watched many older inoperable patients grow weak and die from calcific aortic stenosis in the 1980s, Alain Cribier, MD, FACC, focused on finding a solution. In 1985, he performed the first balloon aortic valvuloplasty, but soon realized its initial success would not last because of restenosis.

In the 1990s, he began exploring the possibility of using a balloon-expandable valve stent to prevent restenosis and replace the diseased aortic valve. The technology of the time, though, made the procedure an imposing challenge.

"My partners trusted me in general, but here they were thinking that I was certainly crazy. That it was impossible to place an artificial valve inside the calcified diseased valve of a patient using regular catheterization techniques," Cribier says of his colleagues at the University of Rouen's Charles Nicolle Hospital, France. All the surgeons explained it was technically impossible, it would occlude the coronary arteries, destroy the mitral valve, crush the septum, create a permanent block, cause strokes and endocarditis and eventually kill the patients, he adds.

After dedicating years to searching for a solution for patients with aortic stenosis, Cribier did not let this criticism get in his way. He went to his university's autopsy lab, where he placed 23-mm stents in fresh specimens of aortic stenosis so he could validate the concept of aortic valve stenting and disprove the naysayers.

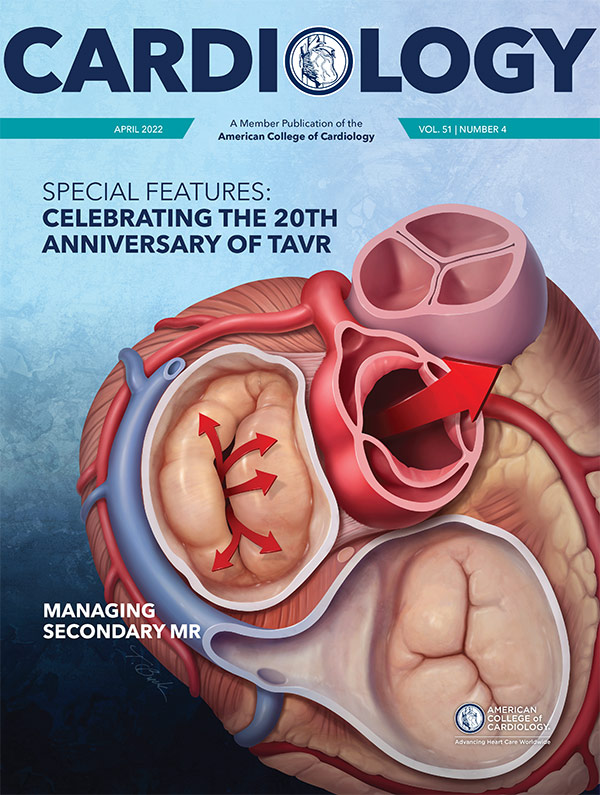

On April 16, 2002, that wild idea finally became a reality when Cribier and his colleagues percutaneously implanted an aortic valve bioprosthesis – the first transcatheter aortic valve replacement now known as TAVR.

The Road to TAVR

Cribier's path to TAVR started in the 1960s, when he chose a career in medicine over that of a concert pianist. At the University of Paris, he became "fascinated" with cardiac surgery, working as an instrumentist at Hôpital Broussais before moving to Rouen to work under Brice Letac, MD. At Charles Nicolle Hospital, he found a home in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, then spent a year at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, working with Jeremy Swan, MD, MACC, and William Ganz, MD, who developed the Swan-Ganz catheter.

"I learned about research there," Cribier says of his time at Cedars-Sinai. "They taught me about innovation and the spirit of innovative medicine. When I returned to Rouen, clinical research was kind of an obsession for me that was mainly aimed at new technologies."

Celebrate 20 Years of TAVR at ACC.22

Join these anniversary events at ACC.22 on the Heart 2 Heart Stage, in the Lounge & Learn Pavilion, Hall D.

Sunday, April 3, 10:30 – 11 a.m.

ACC President's Picks Interview With Dr. Alain Cribier

Join ACC President Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, FACC, for a discussion with Cribier on his work and the lessons learned to date.

Monday, April 4, 7:30 – 8:15 a.m.

Disruptive Innovation: TAVR 20 Years Later

Join Michael J. Mack, MD, MACC, and other TAVR pioneers for a conversation about ways disruptive innovation can deliver far-reaching transformational change in care delivery.

For Cribier, one of the greatest unmet needs was helping patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis who were rejected for surgical valve replacement because of their high operative risk. The first major step in developing a treatment was the balloon valvuloplasty, later followed by the use of devices and techniques required for TAVR, even when many were skeptical. In 1999, Cribier became one of the founders of Percutaneous Valve Technologies, whose engineers in Israel developed models for a balloon-expandable transcatheter heart valve. After three years of preclinical laboratory tests and work on an animal model with his colleague, Helene Eltchaninoff, MD, the transition to human implantation was ready.

The first TAVR patient was a 57-year-old man who presented with severe aortic stenosis, cardiogenic shock with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 12% and multiple comorbidities. Another early TAVR patient who was near death grew strong enough within a year to travel to the U.S. to speak at a conference about her procedure.

"This was so fantastic. I started to think the technique should be spreading more and that indications could be less severe," Cribier says. "I started to move from the critical patients to the high-risk patients. I was again surprised to see the improvement in this population."

Since then, thousands of patients have been included in registries, then in major randomized trials with a stepwise decrease in their surgical risk. These studies constantly showed the noninferiority or superiority of TAVR over surgery, he says.

The Future of TAVR

At age 76, Cribier is now a professor emeritus at the University of Rouen and focuses on his role as co-director at the Rouen Medical Training Center, where he continues to teach TAVR techniques and look for ways to expand its impact.

Moving forward, Cribier expects a 10% annual increase in the number of patients receiving TAVR for several reasons. The first is improved technology and the simplification of procedures. TAVR is now performed in more than 90% of cases using a minimalist transfemoral approach and local anesthesia, with a short length of stay and no rehabilitation program, he says. The second reason is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of TAVR to treat low-risk patients.

"Also, we can anticipate a progressive decrease in the cost of TAVR with time. The only thing we don't know very well right now is the durability of these prostheses, even though there is no alarm in the long-term so far," he says. "I am very confident about the future of this procedure. I can see it being used for treating other valves. I am happy that TAVR has catalyzed the onset of several other transcatheter techniques for the treatment of valvular diseases."

The persistence shown during the development of TAVR sets an example for other researchers, Cribier says.

"When you decide to innovate in medicine, you have a number of people against you," he says. "The biggest lesson is to make sure you're right, then persevere and try to jump all obstacles in your way. Never be discouraged." He adds, "I just had to continue and prove that what I had in mind would be useful for patients. I never thought about giving up, but I confess it was a lot of work and I had many sleepless nights. But 20 years later, what a reward!"

Celebrating Disruptive Technology

To mark the 20th anniversary of Cribier's groundbreaking procedure, Cribier was the recipient of ACC.22's Presidential Citation. "Each year, the ACC President has the great privilege of recognizing an individual who has made outstanding contributions to the field of cardiology and/or the broader field of medicine with the Presidential Citation," says ACC President Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, FACC. "This year, I'm proud to recognize Dr. Cribier with this honor for his unwavering commitment to a seemingly impossible 'project' that today is saving lives and giving hope to hundreds of thousands of patients worldwide."

According to Itchhaporia, Cribier's leadership and contributions in moving TAVR from concept to reality is a prime example of just how disruptive innovation and multi-disciplinary collaboration and teamwork can go hand-in-hand to deliver far-reaching, transformational change in care delivery.

"Optimizing Innovation and knowledge are concepts embedded in the ACC's Vision and vital to achieving the College's overall Mission to transform cardiovascular care and improve heart health," she says. "As we look back on the transformational success story that is TAVR, Dr. Cribier and his life's work are reminders that transformation is not only possible, but within our reach."

Clinical Topics: Cardiac Surgery, Geriatric Cardiology, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Valvular Heart Disease, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Acute Heart Failure, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Aged, Anesthesia, Local, Aortic Valve, Aortic Valve Stenosis, Autopsy, Balloon Valvuloplasty, Bioprosthesis, Cardiac Catheterization, Cardiology, Catalysis, Catheters, Coronary Vessels, Endocarditis, France, Hospitals, Israel, Laboratories, Leadership, Length of Stay, Los Angeles, Middle Aged, Mitral Valve, Models, Animal, Obsessive Behavior, Prostheses and Implants, Registries, Reward, Shock, Cardiogenic, Stents, Stroke, Stroke Volume, Surgeons, Surgical Instruments, Technology, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, United States Food and Drug Administration, Ventricular Function, Left, ACC22, ACC Annual Scientific Session, ACC Scientific Session Newspaper

< Back to Listings