Feature | Infective Endocarditis: Words of Caution For Management

Clinical manifestations of infective endocarditis (IE) may be limited to the heart or can involve extracardiac structures due to vascular-embolic and immune-mediated events. IE is associated with significant complications and mortality, many times due to a delay in detecting clinical infection.

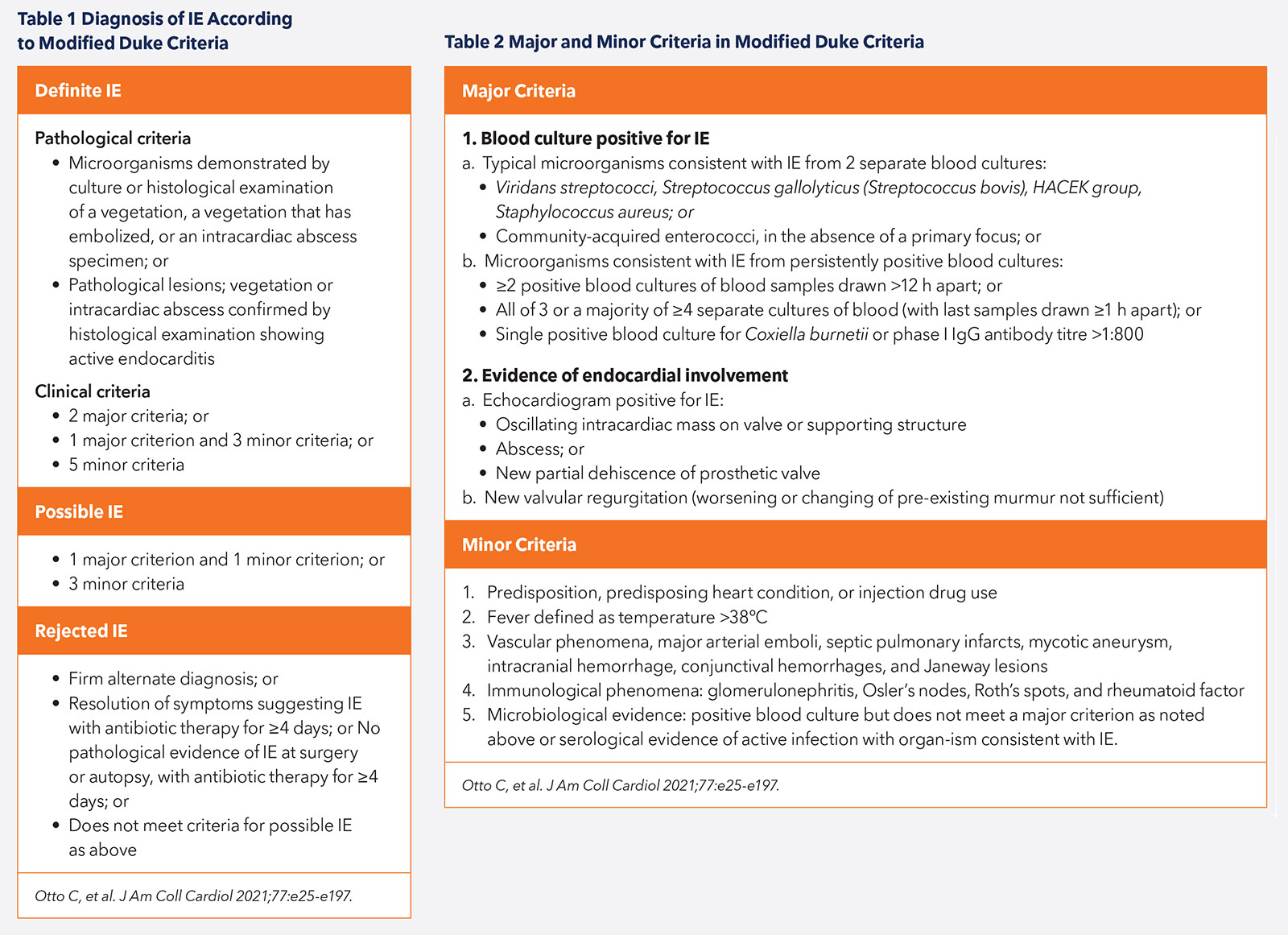

Diagnosis of IE

The diagnosis of IE can be challenging given the nonspecific nature of symptoms and the varying prodrome that may lead to patient presentation. It is therefore crucial to have a high clinical suspicion for infection in those who are at greater risk, such as patients with congenital or valvular heart disease, prosthetic valves or intracardiac devices.

IE should be managed by a collaborative Heart Valve Team comprising, but not limited to, cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, microbiologists, infectious disease specialists and neurologists. The diagnosis of IE is reliant on clinical features, laboratory markers, microbiological identification of organisms, imaging techniques and histologic examination.1

Patients commonly present with symptoms of fever or chills, malaise, weight loss and loss of appetite. New or louder heart murmurs, conduction disease or heart failure (HF) due to significant valvular regurgitation may be evident clinically. Characteristic peripheral stigmata such as Osler's nodes, Janeway lesions, splinter hemorrhages and Roth's spots may also be present. Three in 10 patients may present with an embolic phenomenon such as stroke (Tables 1 and 2).2-4

Laboratory features of IE are nonspecific and should be considered in relation to the overall clinical picture. A pro-inflammatory picture may be seen, with leukocytosis or leukopenia, raised C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and procalcitonin. Hemolysis may lead to anemia and severe end-organ dysfunction can result in elevated lactate levels, thrombocytopenia, and derangements in renal and liver function tests. Bacteremia plays a crucial role in the diagnosis and management of IE based on microbiological identification and sensitivity.

Recommendations for laboratory testing include collecting three sets of peripheral blood cultures using aseptic technique, at least 30 minutes apart but ideally >six hours, before the initiation of antibiotic therapy. Ten percent of patients have culture-negative endocarditis due to infection with fastidious microbes or pre-culture antibiotic administration.

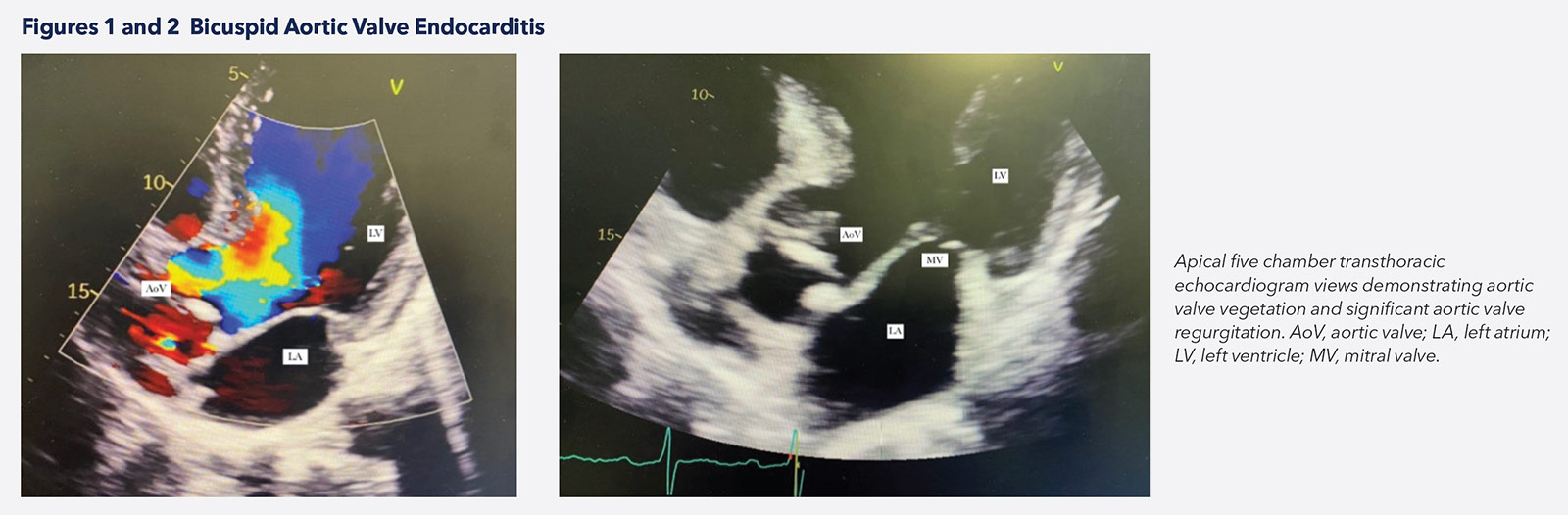

Despite many imaging advances in the diagnosis of IE, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) remains the first-line approach given its availability and cost (Figures 1, 2). TTE is also important in the monitoring and prognostication of patients when diagnosis is established. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is performed in cases of negative TTE with high clinical suspicion, and to evaluate local complications in patients with positive TTE.4-6

TEE has a lower sensitivity for the diagnosis of IE in prosthetic valves and intracardiac devices compared with native valves, giving way to computed tomography (CT) and nuclear imaging techniques.

Multislice CT is superior to echocardiography for detecting complications of IE such as abscesses, pseudoaneurysm, fistula and extracardiac embolization, but it is less sensitive for detecting valvular vegetations. Nuclear techniques are important when clinical diagnosis remains a challenge, especially in the presence of prosthetic valve disease. Several reports highlight the utility of SPECT/CT and FDG-PET 7,8 in reducing misdiagnosed cases of IE. However, there are limitations in patients who underwent recent cardiac surgery given the inability to distinguish postoperative inflammation from infection. MRI aids in the diagnosis of intracranial complications and manifestations such as ischemic lesions, intraparenchymal hemorrhages, abscesses or mycotic aneurysms, as well as abdominal visceral lesions.

Antibiotic Management

Knowledge in Action: JACC Patient Care Pathways

JACC Patient Care Pathways offers an immersive multimedia experience illustrating the cross-specialty decision-making involved with treating patients in an acute care setting. Geared toward clinicians spanning the entire cardiovascular care team and all career stages, the new online offering provides the personal, collegial feel of Grand Rounds in an interactive patient timeline format. Images, video and expert discussion clips are incorporated, detailing the teamwork and evidence-based decision-making necessary for optimal patient outcomes. Visit JACC.org/jacc-patient-pathways to learn more and to access the debut case on infective endocarditis.

Effective antimicrobial therapy in IE relies on the sterilization of vegetations and microbial eradication.1 Surgical intervention also plays an important role in the removal of infected material and drainage of abscesses. There are several unique characteristics of the infected vegetations found in IE that pose a variety of challenges for treatment.

Vegetations often consist of densely packed bacteria interlocked within a biofilm comprised of fibrin and platelets. This creates a mechanical barrier and limits antibiotic penetration to the embedded microorganism.2 The high bacterial density results in a higher than anticipated effective minimum inhibitory concentration of antibiotics. Bacteria susceptible to the effects of bactericidal antibiotics, such as beta-lactams, at low densities, can be relatively resistant or tolerant in dense populations. Bacterial growth within these biofilms also consists of slow growing or dormant bacteria, which display phenotypic tolerance towards most antimicrobials.2,3

The duration of antibiotic treatment must be sufficient to ensure complete eradication of microorganisms within biofilms and often lasts between two to six weeks. Due to the high bacterial densities and slow bactericidal activity of some antibiotics, prolonged treatment is often required. Vegetation burden, area of involvement, type of valve affected (native vs. prosthetic) and isolated pathogen are other factors that affect treatment duration.1

The 2015 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline for IE management and the American Heart Association's scientific statement on IE serve as the basis for these recommendations for antibiotic management.1,9

In both native valve endocarditis (NVE) and prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE), the duration is based on the first day of effective antibiotic therapy. This is defined as a negative blood culture after an initial positive culture was obtained.

Two sets of blood cultures should be taken every 24-48 hours until a negative culture is obtained.

In cases of NVE requiring surgical intervention, if operative tissue cultures are positive, a new full course of treatment should be initiated, with choice of antibiotic tailored to the sensitivities of the latest isolated pathogen. If operative tissues are culture negative, the number of days of antibiotic therapy administered before surgery can be counted towards the overall duration.

ESC guidance states that in cases of NVE requiring prosthetic valve replacements, the specific postoperative regime should be the regime initially recommended for NVE, not PVE. This differs from the AHA scientific statement which states there is a lack of consensus surrounding this topic.

Treatment Guidance

In all suspected cases of IE, prompt treatment should be initiated. The ESC guideline states that if the patient's clinical status allows for a slight delay in treatment, three sets of blood cultures should be drawn at 30-minute intervals prior to starting antibiotics.1 Where possible, antibiotic therapy should be pathogen-targeted, however in the acute phase empirical treatment can be started. The choice of empirical therapy will depend on several factors, including:1,9

- Prior antibiotics the patient may have received recently.

- Nature of the valve affected (native or prosthetic).

- If PVE is suspected, whether the infection is within one year of surgery (early or late PVE).

- Likely source of infection (community-acquired or nosocomial).

- Local epidemiology and antibiotic resistance.

Both the ESC and AHA guidance states that ideally three sets of blood cultures should be drawn from different venepuncture sites at 30-minute intervals before starting antibiotics, if the patient's clinical status allows for a brief delay in treatment. Consult should be sought from an infection specialist before initiating empiric antibiotics because the choice of antibiotic will depend on several factors, including:2,3

- Prior antibiotic therapy the patient may have received.

- NVE or PVE (early vs. late PVE).

- Source of infection (community-acquired, nosocomial).

- Local epidemiology and antibiotic resistance.

The current guidance for empirical treatment from the ESC is summarized in the guideline document in the European Heart Journal. Once a pathogen is isolated, ideally within 48 hours, antibiotic therapy should be tailored.

Community-acquired native valvular endocarditis or late prosthetic valve endocarditis is treated with a combination of ampicillin, flucloxacillin and gentamicin or vancomycin and gentamycin for patients allergic to penicillin, in order to cover for staphylococci, streptococci and enterococci. Vancomycin, gentamicin and rifampicin are recommended in early prosthetic valve endocarditis or nosocomial- and non–nosocomial-associated endocarditis (to cover for MRSA and ideally non-HACEK gram negative pathogens). Enterococcal IE is most commonly caused by enterococcus faecalis, which can be highly resistant to antibiotic-induced killing and can have multiple drugs including aminoglycosides, beta-lactams and vancomycin. Eradication often requires prolonged administration (up to six weeks).

The addition of aminoglycosides in MRSA or MSSA NVE is no longer recommended by the ESC or AHA, because its use has not been associated with clinical benefit and it can increase renal toxicity. Regarding the management of staphylococcal IE in intravenous drug use, the AHA scientific statement suggests either parenteral beta-lactam or daptomycin short-course therapy is adequate for the treatment of uncomplicated MSSA right-sided IE.9 For streptococcal PVE, the AHA statement suggests aqueous crystalline penicillin G or ceftriaxone for six weeks with or without gentamicin for the first two weeks. In patients with a penicillin allergy, vancomycin use is advised.9

Surgical/Interventional Management

Surgical management of IE is a decision for the Heart Valve Team to balance the risk and outcomes together with patient's comorbidities. An example of this team decision-making is showcased in the inaugural manuscript from the JACC Patient Pathways initiative,10 which presented a case of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis.

Surgery is first-line management in patients who have decompensated HF, despite optimal medical therapy with antibiotics. Early surgery while the patient is receiving antibiotic treatment is indicated to avoid progressive HF and irreversible structural damage caused by severe infection as well as to prevent systemic embolism.

Therefore, indications for surgery include:

- HF (severe aortic or mitral regurgitation, intracardiac fistulae or valve obstruction caused by vegetations).

- Patients without HF but with high filling pressures.

- Uncontrolled infection.

- Infection due to resistant or very virulent organisms.

- Perivalvular extension of IE (abscess formation, pseudoaneurysms, fistulae).

- Recurrent infection with worsening valvular involvement.

Echocardiography plays a major role in the follow-up of critically ill patients with IE and the determination of surgery. The size of the vegetation (if >10 mm) predisposes the patient to higher risk of embolic events; if the vegetations are increasing in size in the case of aggressive microorganisms, the detection of perivalvular infection, such as an aortic abscess, will determine timing for surgery. In prosthetic valves, the question of surgery may be answered with advanced imaging modalities such as PET or ECG-gated CT.

Surgery: Repair or Replacement?

The objective of surgical management is complete removal of infected tissues and reconstruction of cardiac morphology, including repair or replacement of the affected valve(s). In the JACC Patient Pathways case,10 in the setting of extensive destruction of the mitral valve, the surgeon deserved praise for his intraoperative work, in which he was able to repair both the mitral and tricuspid valves in a young woman with the potential of a future pregnancy.

If the valve cannot be repaired, inevitably valve replacement is the only way out. In patients who are intravenous drug users, repair may be preferable to avoid risk of recurrence with valve replacement (prosthetic material). In the case of reinfection, again valve replacement may be the only surgical choice.

Device and Lead Extraction

In the case of definite IE of a cardiac device, medical therapy alone has been associated with high mortality and risk of recurrence.1,9 Therefore, device and lead removal is recommended in all cases of proven endocarditis. The need for extraction also should be suspected in the case of infection without another apparent source. Considering the inherent risk of an open surgical procedure, transvenous lead extraction has become the preferred method. Transvenous extractions are not without risk, and procedural complexity may vary significantly according to lead type and features. An expert heart center is essential in such complex cases of IE.

Patient-Centered Care: From Guidance to Action

There is a vital need for prompt diagnosis and management of IE. Current guidelines assist the understanding of complex antibiotic and surgical management. The clinical case of a complex patient with IE presented as part of the JACC Patient Pathways illustrates a team-based approach to applying this guidance.

This article was authored by Rheana Harrilal, MD, MPH; Darshana Nair, MD; and Julia Grapsa, MD, PhD, FACC, all from the department of cardiology, Guys and St Thomas NHS Trust, London, UK. Grapsa is editor-in-chief of JACC: Case Reports.

References

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes M, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J 2015;36:3075-3128.

- Horgan S, Mediratta A, Gillam L. Cardiovascular imaging in infective endocarditis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13(7):e008956.

- Pretet V, Blondet C, Ruch Y, et al. Advantages of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging over modified Duke criteria and clinical presumption in patients with challenging suspicion of infective endocarditis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:720.

- Otto C, Nishimura R, Bonow R, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:e25-e197.

- Rajani R, Klein J. Infective endocarditis: A contemporary update. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20:31-5.

- Shafiyi A, Anavekar N, Virk A, et al. Repeat transesophageal echocardiography in infective endocarditis: An analysis of contemporary utilization. Echocardiography 2020;37;891-9.

- Ten Hove D, Slart RHJA, Sinha B, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT in infective endocarditis: Indications and approaches for standardization. Curr Cardiol Rep 2021;23:130.

- Xie P, Zhuang X, Liu M, et al. An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of echocardiography for adult infective endocarditis–the timing and mode of assessment (TTE or TEE). BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:92.

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;13;132:1435-86.

- Grapsa J, Blauth C, Chandrashekhar YS, et al. Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis: JACC Patient Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:88-99.

Clinical Topics: Anticoagulation Management, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Valvular Heart Disease, Vascular Medicine, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Acute Heart Failure, Heart Failure and Cardiac Biomarkers, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Computed Tomography, Echocardiography/Ultrasound, Nuclear Imaging, Mitral Regurgitation

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Abscess, American Heart Association, Aminoglycosides, Aneurysm, False, Aneurysm, Infected, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Anti-Infective Agents, Appetite, Bacteremia, Bacteria, beta-Lactams, Biofilms, Blood Culture, Blood Platelets, Blood Sedimentation, Cardiac Surgical Procedures, Cardiologists, Cardiology, Ceftriaxone, Chills, Consensus, C-Reactive Protein, Critical Illness, Cross Infection, Defibrillators, Implantable, Diagnostic Errors, Drainage, Drug Resistance, Microbial, Drug Users, Duration of Therapy, Echocardiography, Echocardiography, Transesophageal, Electrocardiography, Embolism, Endocarditis, Endocarditis, Bacterial, Enterococcus faecalis, Fibrin, Fistula, Fluorodeoxyglucose F18, Follow-Up Studies, Gentamicins, Heart Failure, Heart Valve Diseases, Heart Valve Prosthesis, Heart Valves, Hemolysis, Hemorrhage, Homicide, Hypersensitivity, Infection Control, Laboratories, Leukocytosis, Leukopenia, Liver Function Tests, London, Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Microbial Sensitivity Tests, Mitral Valve, Mitral Valve Insufficiency, Multimedia, Multiple Organ Failure, Neurologists, Patient Care Team, Patient-Centered Care, Penicillin G, Penicillins, Pharmaceutical Preparations, Positron-Emission Tomography, Pregnancy, Procalcitonin, Reinfection, Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography Computed Tomography, Staphylococcus aureus, State Medicine, Sterilization, Stroke, Substance Abuse, Intravenous, Surgeons, Surgical Instruments, Teaching Rounds, Thrombocytopenia, Time-to-Treatment, Tomography, X-Ray Computed, Tricuspid Valve, Vancomycin, Weight Loss

< Back to Listings