Cover Story | Hidden in Plain Sight: SCAD as a Major Cause of MI in Women

The 34-year-old woman arrived at the emergency department (ED) with crushing chest pain, diaphoresis and nausea. Her ECG showed ST-elevation in the anterior leads and her troponin levels were markedly elevated. She had no traditional cardiovascular risk factors and had delivered her second child six weeks earlier. Emergency cardiac catheterization revealed what appeared to be a "hazy" stenosis in the mid-left anterior descending artery (LAD), with TIMI 2 flow. The interventional cardiologist performed optical coherence tomography (OCT), which revealed an intramural hematoma with a false lumen – the hallmark of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD).

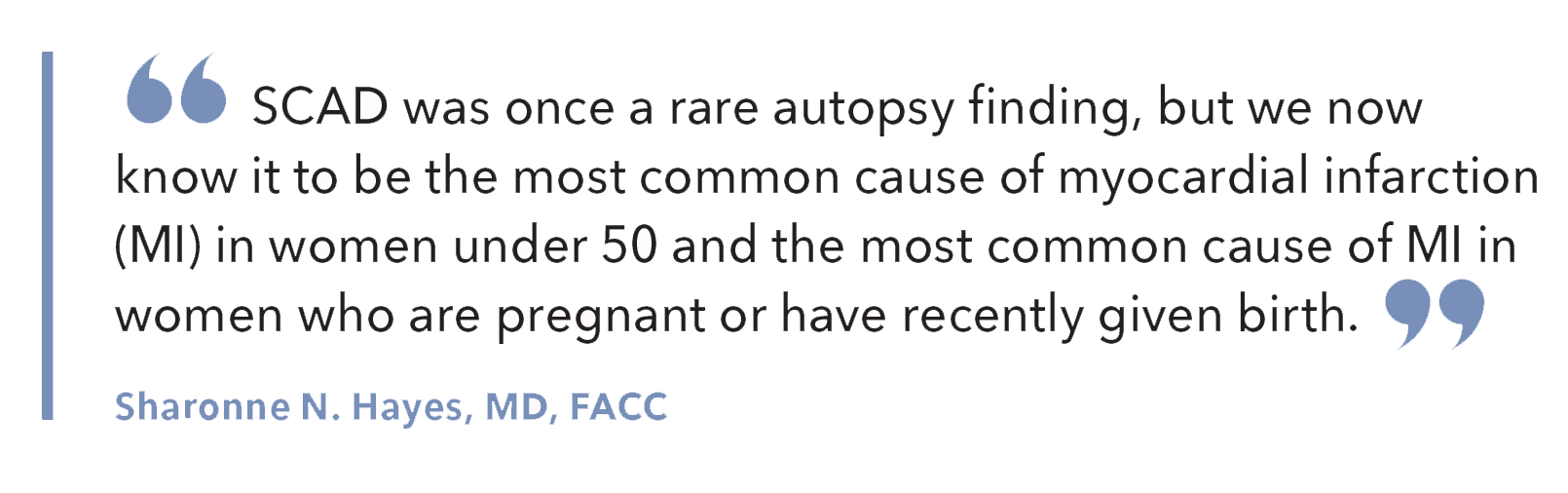

"SCAD was once a rare autopsy finding, but we now know it to be the most common cause of myocardial infarction (MI) in women under 50 and the most common cause of MI in women who are pregnant or have recently given birth," says Sharonne N. Hayes, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, where she helps lead the SCAD Research Program.

SCAD represents a fundamentally different pathophysiological process from atherosclerotic coronary disease. The condition involves the spontaneous (i.e., neither traumatic nor iatrogenic) development of an intramural hematoma within the tunica media, leading to the separation of arterial wall layers and compression of the true lumen, resulting in myocardial ischemia and infarction.

Hayes reflects with "humility" on her early days in cardiology when she felt certain she was unlikely to see more than a handful of SCAD cases in her career. "When we first opened the Women's Heart Clinic at Mayo in 1998, I started seeing a few more SCAD patients than I'd been told I would, but each case was considered unusual," says Hayes.

Hayes' perspective changed in 2009 when she was approached by a group of women who had survived a SCAD and had organized more than 70 SCAD survivors in the online support community of WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease. The number 70 caught her attention because the largest published series of SCAD patients at the time included only 42 individuals.

Around that time, Hayes and Marysia S. Tweet, MD, MS, FACC, then an internal medicine resident at Mayo (and still at Mayo), started the Mayo Clinic SCAD Registry, which now includes almost 1,800 SCAD patients and has led to more than 70 publications since 2011. The registry is virtual and is open to all to add patients who have experienced SCAD.

In 2012, three landmark publications fundamentally changed how clinicians approach SCAD, transforming it from a rare curiosity managed with aggressive intervention into a recognized clinical entity requiring evidence-based conservative care.

The first paper, published by Fernando Alfonso, MD, PhD, and colleagues, demonstrated that conservative management could be highly effective in SCAD patients.2 This first large, prospective analysis of 45 consecutive patients challenged conventional wisdom by showing that spontaneous healing occurred in most cases when managed conservatively. The second paper, a case series of six patients published by Jaqueline W.L. Saw, MD, FACC, and colleagues, identified the association between SCAD and fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD).3

Simultaneously, Tweet and the Mayo team published their seminal work analyzing 87 patients with SCAD.4 They also found the association between SCAD and FMD and reported an uncomplicated hospital course among those treated conservatively but high technical failure among those treated with PCI.

A subsequent 2014 study of 189 patients showed that PCI carried a 53% procedural failure rate and did not protect against target vessel revascularization or recurrent SCAD. The research established that conservative management was not only safer but often more effective than invasive approaches.5

Young Hearts, Torn Apart

Single-center studies suggest that SCAD accounts for up to 4% of all acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and as much as 35% of MIs in women under 50.1 While SCAD predominantly affects women, men are not immune.

"Ironically, men with SCAD are sometimes marginalized," notes Hayes. "I've always advocated for better understanding of sex and gender cardiology, so everyone receives proper treatment. Also, because understanding SCAD in men will likely help us better understand the pathophysiology and treatments for SCAD in women."

Traditional cardiovascular risk factors are notably less prevalent in SCAD patients compared to atherosclerotic MI populations. However, hypertension (32% to 37%) and hyperlipidemia (20% to 35%) do occur in SCAD patients at rates similar with age- and sex-matched populations, challenging the notion that SCAD occurs exclusively in completely healthy individuals.

Migraine headaches show an intriguing association with SCAD, with prevalence rates significantly higher than in the general population. Some studies suggest that migraine patients may have underlying arterial wall abnormalities that predispose to both conditions.

Hormonal influences have also been implicated with the development of SCAD, but studies show that SCAD can affect women who have never been pregnant and those already postmenopausal, making the association unclear. Also, there is no clear evidence that exogenous hormone use, either pre- or postmenopause, affects the risk of SCAD or its recurrence (although exogenous hormones are not recommended in women who have had SCAD, notes Hayes).

Pregnancy-associated SCAD (P-SCAD) can occur at any time during or after pregnancy, but upwards of 70% occur in the first week postpartum. P-SCAD accounts for between 15-43% of pregnancy-associated acute MI, affecting about 1.81 per 100,000 pregnancies.1

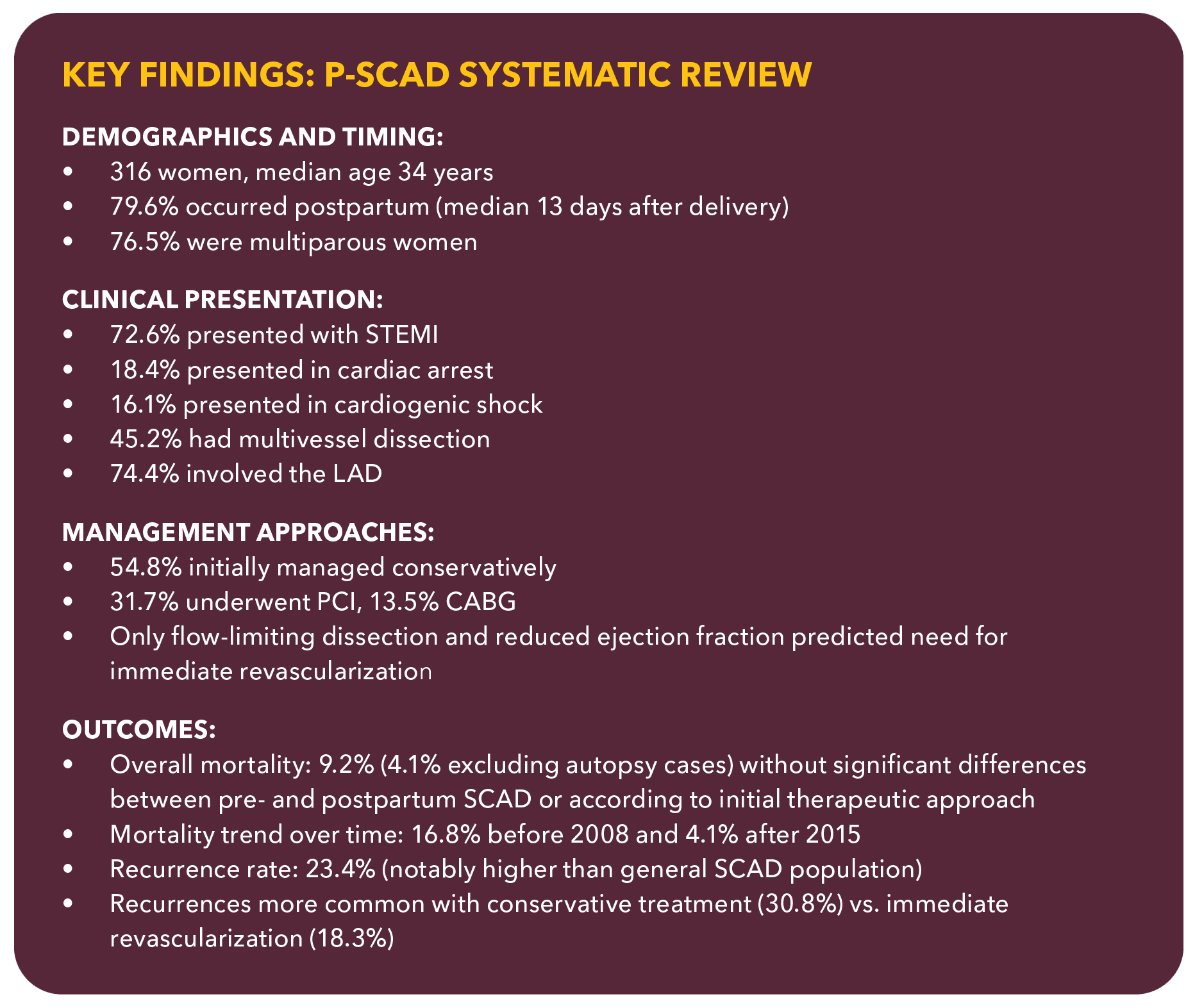

As compared to non–P-SCAD, women with P-SCAD tend to have a more severe clinical presentation with impaired left ventricular function, cardiogenic shock and multivessel dissection.6 A 2025 systematic review by Milani, et al., aimed to synthesize all available case-level data on P-SCAD to describe its presentation, management, outcomes and recurrence patterns (See Key Findings Box).6

Precipitating Factors in SCAD

"When looking at the landscape of who SCAD affects beyond P-SCAD, we see about 25% of non–P-SCAD patients report doing extreme exercise at the time of their event or experiencing extreme emotional stressors," says Tweet.

In a larger subset, no obvious trigger is identified, and in yet another large proportion of SCAD patients, "underlying arterial abnormalities are identified and we suspect genetic predisposition plays a role, although that's not yet been proven," she adds.

Tweet has an NIH-funded K23 grant to investigate the autonomic nervous system's role in SCAD to improve prevention and treatment. Her research is using microneurography to directly assess sympathetic nervous system responses to stress, along with hemodynamic monitoring and cerebral blood flow measurements during physical and emotional stressors.

While still analyzing data, preliminary findings suggest meaningful differences between SCAD patients and controls, she notes. Understanding these differences could prove crucial for developing targeted treatments and prevention strategies for this condition.

FMD represents one of the strongest associations with SCAD, present in 40-70% of SCAD patients depending on the imaging protocol used, says Esther SH Kim, MD, FACC, from Atrium Health Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute Kenilworth in Charlotte, NC.

Kim is the principal investigator of the iSCAD Registry, a multicenter registry of nearly 30 sites that has enrolled more than 2,100 patients since 2019. She co-chaired (with Hayes and Saw) a Scientific Statement on SCAD and was an author on the International Consensus Statement on FMD.7,8

"When I see a patient with SCAD, I think, why in the world did the coronaries dissect? I believe SCAD is a manifestation of an underlying arteriopathy, often FMD, in many, if not most, patients," she says.

FMD is a nonatherosclerotic, noninflammatory arterial disease that can affect multiple vascular beds, most commonly including the renal and carotid arteries. According to Kim, it is best known as a cause of arterial stenosis, but it can also lead to arterial aneurysm and dissection. "The association between SCAD and FMD fits with what we know about FMD," says Kim, "but SCAD is also associated with aneurysm and noncoronary arterial dissection even in the absence of FMD, so it's important to consider vascular imaging in all patients with SCAD."

Catching an Uncommon Diagnosis

While no longer considered rare, SCAD is uncommon enough that keeping attuned to its possible presence remains crucial.

"There are opportunities to make mistakes at every step of the process," notes Kim. "I've had patients who presented with chest pain to the ED and right before they're about to be discharged with the diagnosis of a panic attack, the troponin comes back abnormal and they are told, 'Oh, you're having a heart attack.'"

The clinical presentation of SCAD is similar with that of atherosclerotic ACS. ECG findings mirror those seen in atherosclerotic ACS, with STEMI and NSTEMI presentations occurring with similar frequency. Cardiac biomarkers, including troponin levels, are typically elevated. The primary difference lies in patient phenotype rather than symptoms.

However, increased awareness has created new challenges. "Ironically, now we're sometimes in the position of trying to tell people that not everything you see in a young woman is SCAD," Kim notes. She was recently consulted on a transgender female patient who presented with NSTEMI and an LAD lesion. "She was just different estrogen hormones, so it was assumed she had SCAD, but on IVUS we found plaque."

Where the diagnostic rubber hits the road is during coronary angiography, where SCAD may present with subtle or ambiguous findings. One question that comes up often, says Kim, is whether coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is sufficient in a woman who presents with chest pain and positive troponin. "CCTA is not great at seeing the smaller arteries, so I'm afraid it may miss a SCAD in a branch vessel," she notes. Angiography remains the best option using the Saw classification for the type of SCAD.9

Type 1 SCAD, with its characteristic multiple lumens or contrast staining of the arterial wall, is relatively straightforward to recognize. However, Type 2 and Type 3 SCAD can be more challenging, appearing as diffuse narrowing or focal stenosis that may be mistaken for atherosclerotic disease, coronary spasm or technical artifacts.

Advanced intracoronary imaging techniques have revolutionized SCAD diagnosis and should be considered in cases where the angiographic appearance is ambiguous. "I encourage clinicians, if they are uncertain about the diagnosis of SCAD, to do the testing necessary to convince yourself it's SCAD," Kim notes.

"During angiography, when deemed safe to do so, this includes intracoronary nitroglycerin to make sure it's not vasospasm or intracoronary imaging. After angiography, noninvasive coronary imaging with CCTA can help visualize intramural hematoma and vascular imaging demonstrating FMD can also be helpful."

OCT provides high-resolution cross-sectional images and can clearly demonstrate intramural hematoma, false lumen and intimal disruption characteristic of SCAD. IVUS can also aid in diagnosis, though its lower resolution compared to OCT may limit its utility in some cases.

Treatment Considerations

Currently, there are no randomized controlled trials to guide SCAD-specific management. Conservative management has become the standard of care for hemodynamically stable patients with preserved coronary flow, based on observations that coronary dissections often heal spontaneously. Improvement in luminal dimensions and restoration of normal flow occur in 70-95% of conservatively managed patients over weeks to months, supporting patient observation rather than immediate intervention.

Medical therapy differs significantly from standard ACS management. "The treatment for SCAD does not involve anticoagulation," notes Hayes. "Once we make that diagnosis, there is a theoretical risk; if there's an intramural hematoma, it could bleed more and cause further obstruction or extend the dissection. Moreover, these lesions are not typically associated with significant thrombus."

Beta-blocker therapy is generally recommended for the same reasons it's prescribed after any MI. Additionally one observational study suggests beta-blockers may reduce recurrence risk.

Antiplatelet therapy decisions require careful consideration. "I think the jury is still out regarding antiplatelet therapy," says Tweet. "If a patient has a stent, I'll prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy for that first year after the heart attack; otherwise, there's often no reason for them to be on two agents, and I typically keep them on aspirin alone. We need more evidence to know what is best for SCAD patients in the short- and long-term, however."

Blood pressure control represents a crucial long-term management strategy. "I'm always clear with my patients that we want to maintain good blood pressure control as they age," Hayes emphasizes. "Of course, if they have hyperlipidemia, they should be treated, but that treatment is aimed at reducing their future risk of atherosclerosis, not because we have evidence suggesting that statins reduce the risk of recurrence."

Recurrence, Chest Pain and Other Long-Term Effects

The prognosis for SCAD patients is generally favorable, with in-hospital mortality rates of 1-2% and most patients achieving good long-term functional status. The healing characteristics of SCAD represent one of the most encouraging aspects of the condition.

However, SCAD patients face unique long-term challenges that differ from those with atherosclerotic heart disease. Recurrence represents the primary concern, occurring in approximately 10-20% of patients during extended follow-up, with an annual recurrence rate of 2-3%.

"The vast majority of patients will not have another SCAD. I tell patients they need to live their life as if it won't happen, but they need to be ready and have a plan in case they experience recurrent symptoms," explains Hayes.

Beyond physical concerns, patients face significant emotional challenges. "It's completely abnormal to tear an artery out of the blue, so these patients have legitimate reasons to fear that it won't be a one-off event" says Kim. This reality, coupled with the trauma of the initial event, can lead to substantial anxiety. "PTSD, anxiety, depression – these are all very real and very prevalent post SCAD," she adds.

Indeed, a recent publication from the iSCAD Registry demonstrated that nearly one in three survivors of SCAD may experience clinically significant PTSD symptoms years after their event, along with high rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.10

Post-SCAD chest pain is extremely common and represents a major management challenge. Symptoms may differ from the initial event, occur with mental stress or during perimenstrual periods, and sometimes respond to nitrates despite absence of fixed coronary obstruction. The high frequency of chest pain leads to frequent rehospitalizations and repeat investigations, creating anxiety for both patients and physicians.

Quality of life studies show that while most SCAD patients report good long-term outcomes, a significant minority experience ongoing symptoms, functional limitations or psychological distress.

Proper management of post-SCAD symptoms is crucial for recovery. "I've seen so many patients with nitrate-responsive chest pain who aren't being treated properly and their doctor told them, "It's normal,'" says Hayes. "Chest pain after SCAD is common, but it's not normal and it should be attended to."

She encourages clinicians to listen carefully to chest pain complaints in patients with SCAD. "First of all, their chest pain might actually be related to plaque and they need a stent. Also, a patient who experiences chest pain every few days is not going to heal mentally and move on from their SCAD."

The Critical Role of Cardiac Rehabilitation

Despite its proven benefits, cardiac rehabilitation remains vastly underutilized for SCAD patients. Hayes emphasizes that cardiac rehabilitation is "one of the most cost-effective ways to save lives," yet women and the elderly are among those least likely to be referred, even when they have clear indications. In the case of SCAD, this underutilization is particularly detrimental.

"It's remarkable how many women are told, 'Oh, you were physically active before your event, you're a runner; just go home and heal yourself,'" Hayes observes. "This is a mistake."

The supervised environment of cardiac rehabilitation provides crucial psychological benefits beyond physical conditioning. Patients receive careful assessments, education and supervised exercise with ECG monitoring. When someone feels a concerning sensation technicians can immediately check vitals and provide reassurance.

This monitored experience builds essential confidence for independent activity. "Only after this, when that woman is out walking in the neighborhood and feels the same twitch, will she have the confidence to keep walking," Hayes explains. "The importance of this cannot be underestimated."

Screening For Vascular Abnormalities

Screening for extracoronary vascular abnormalities has become standard practice following SCAD diagnosis. "You really need to do cross-sectional imaging, head to pelvis, on every patient diagnosed with SCAD, preferably with CTA over duplex US," says Kim. The screening detects FMD and other arteriopathies, including intracranial aneurysms in 7-14% of cases, making it an essential component of SCAD patient care.

Physical activity recommendations after SCAD require balancing the cardiovascular benefits of exercise with theoretical recurrence risks. Most experts recommend avoiding extreme endurance training, exercising to exhaustion, competitive sports and activities requiring significant Valsalva maneuvers. However, regular moderate exercise is encouraged, ideally with cardiac rehabilitation program participation when appropriate.

Final Thoughts

The recognition that SCAD accounts for such a substantial proportion of heart attacks in young women has been one of the major revelations in cardiology over the past decade, fundamentally changing how ACS is approached in this demographic.

"This was very much an overlooked condition even 10 years ago when patients were told, 'you're a fluke' or 'you're the only patient I've cared for with this.' Now we're getting much better at recognizing it, which will ultimately lead to better treatment and prevention, which is an area where we need more progress," says Tweet.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Hayes SN, Tweet MS, Adlam D, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:961-84.

- Alfonso F, Paulo M, Lennie V, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: long-term follow-up of a large series of patients prospectively managed with a "conservative" therapeutic strategy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:1062-70.

- Saw J, Poulter R, Fung A, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in patients with fibromuscular dysplasia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:134-7.

- Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2012;126:579-88.

- Tweet MS, Eleid MF, Best PJM, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: revascularization versus conservative therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:777-86.

- Milani M, Bertaina M, Ardissino M, et al. Unveiling an insidious diagnosis and its implications for clinical practice: Individual patient data systematic review of pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Int J Cardiol 2025;418:132582.

- Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e523-e557.

- Gornik HL, Persu A, Adlam D, et al. First International Consensus on the diagnosis and management of fibromuscular dysplasia. Vasc Med Lond Engl 2019;24:164-89.

- Saw J. Coronary angiogram classification of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv Off J Soc Card Angiogr Interv 2014;84:1115-22.

- Sumner JA, Kim ESH, Wood MJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder after spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a report of the International Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2024;13:e032819.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Dyslipidemia, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Coronary Artery Disease

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Myocardial Ischemia, Hyperlipidemias, Coronary Artery Disease