Cover Story | COVID-19 at the Regional Level: Experience and Implications For Pandemics

The COVID-19 crisis has yielded extraordinary danger, difficulties and stress for all of society. Health care personnel and institutions in particular shoulder a tremendous burden.

Worldwide coronavirus infections continue to increase. In the U.S., as winter approaches, there is an alarming number of new cases and deaths reported daily. In the face of this second surge of the pandemic, activities to manage systems of care must be continued, revised and upgraded.

As in many situations of strife, the untoward events are front and center – yet opportunity for learning and improvement abounds. Modern times have not produced such a universal event.

The U.S. has been free of pandemics, famine, major civil unrest or war on our soil for many decades. Other than localized, regional weather events, the U.S. health system has not been in a position to test and refine systems designed to respond to such disruption.

The current "crisis opportunity" allows for evaluation and improvement in our systems of care and responses to better prepare for the future – and any disaster… or the next pandemic. The experience in a single health system (with heavy emphasis on cardiac care) provides insight into the effects and response to the COVID-19 crisis, and lessons learned for future preparedness.

Lee Health is a public, not-for-profit health system in Southwest Florida, operating four acute care hospitals and two specialty hospitals, in addition to extensive outpatient facilities. The primary service area is Lee County, with a permanent population of 770,000; the population is significantly higher during winter months.

The Pandemic

The pandemic started in Southwest Florida on March 6, with the first case of COVID-19 in the area (and the second case in the state of Florida). In anticipation of this, the Lee Health COVID Task Force had been formed and activated on February 10.

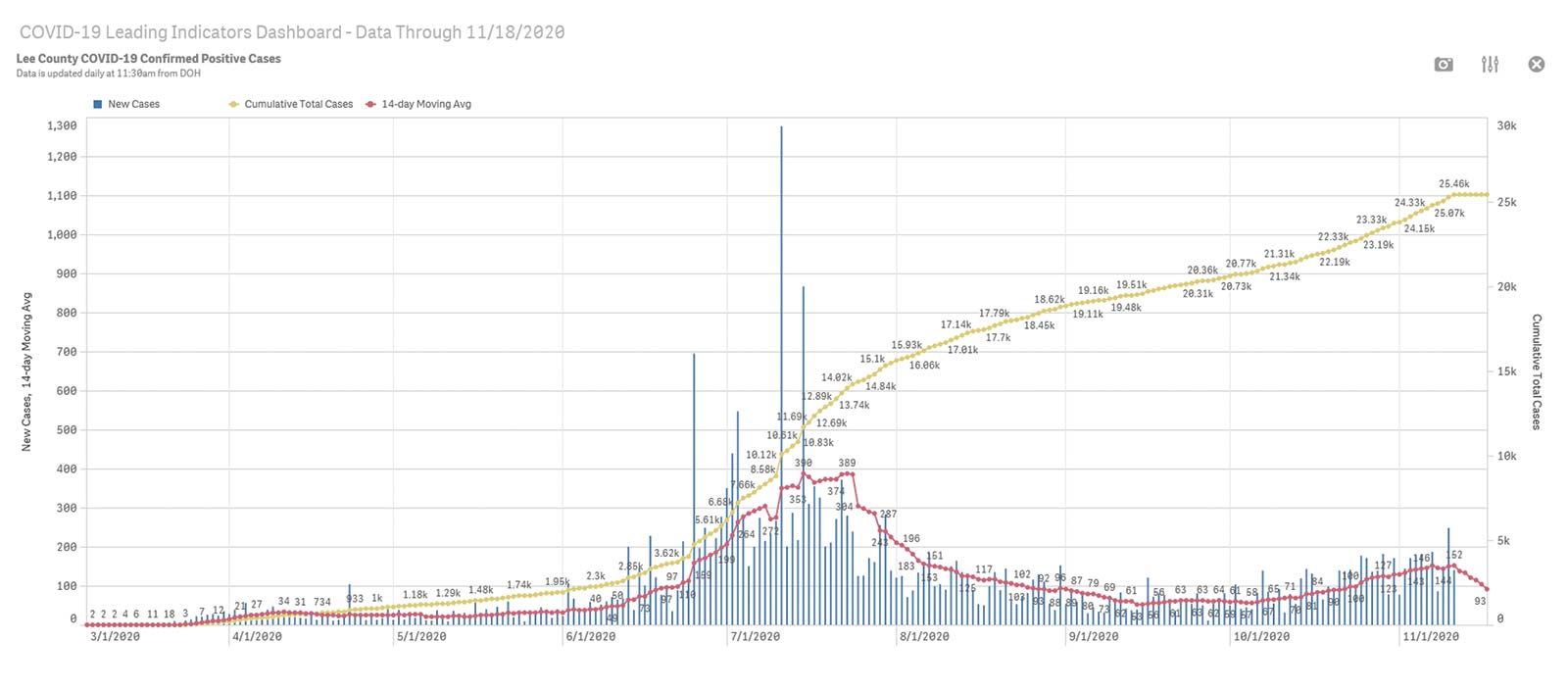

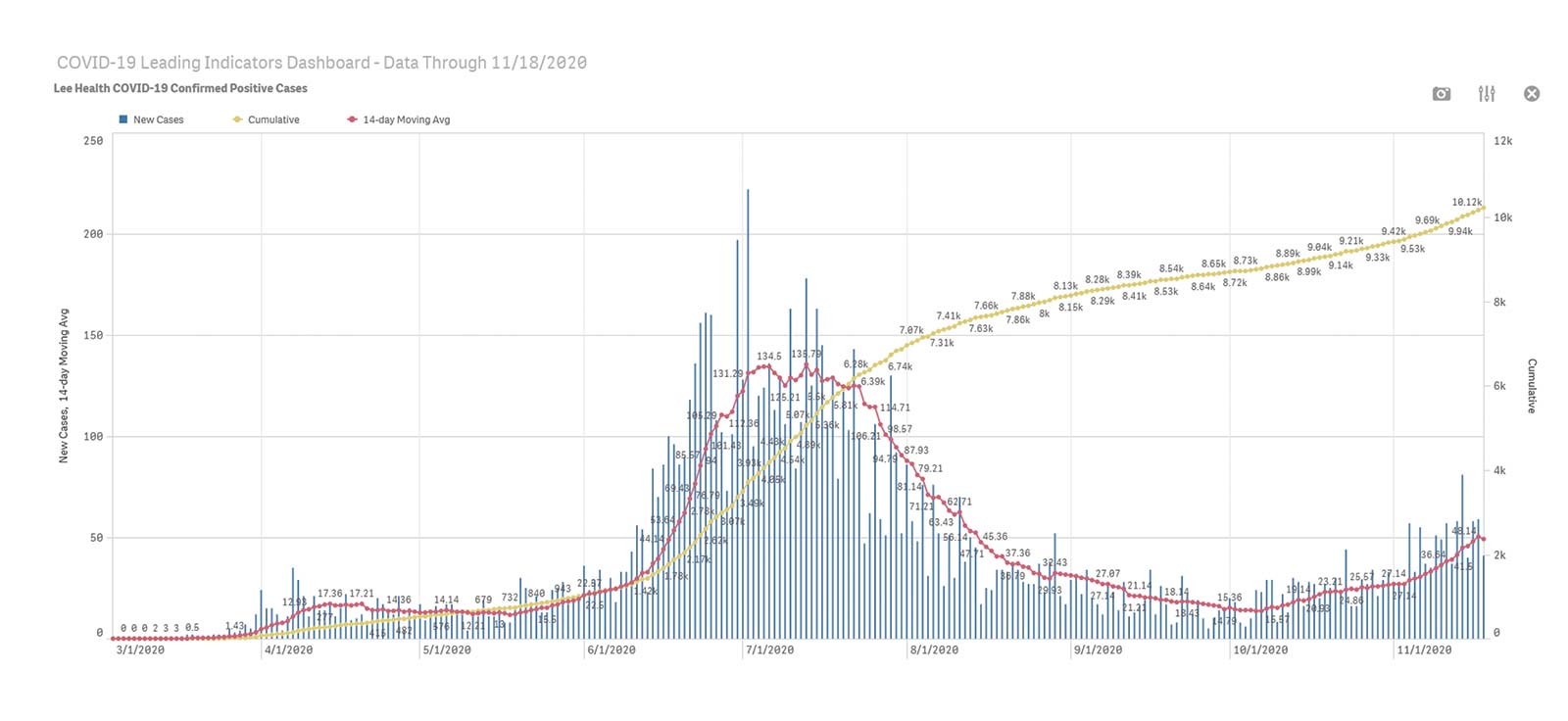

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the COVID-19 case volumes in Lee County and Lee Health, respectively, through November 10. At the time of this writing, volumes are increasing with an anticipated second surge impending.

During the first surge in the spring of 2020, Lee Health experienced 113 employees (of 14,000) who tested positive for coronavirus infection, with 63% from community exposure and 37% from work-related exposure. Nonetheless, the number of infected (or ill) employees belies the impact that exposures and quarantines had on patient care.

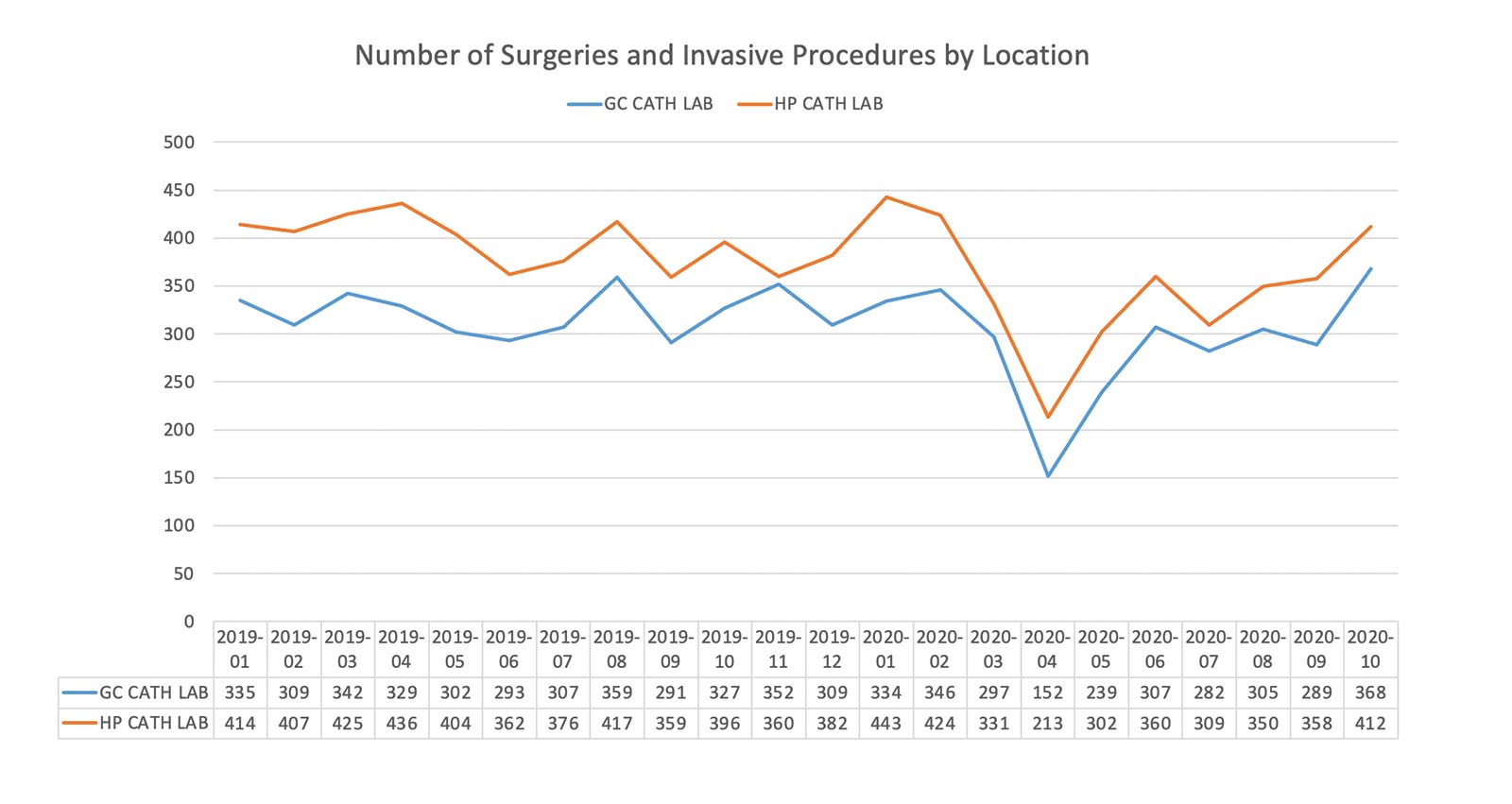

During the surge, elective cardiac procedures (along with surgeries) were halted or slowed, dependent on "space, staff and stuff," as guided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) preparedness planning tool, as well as administrative directives, based on volume and risk assessments.

An example of the impact is demonstrated in Figure 3, showing catheterization laboratory procedures at two hospitals in the Lee Health System.

Space: Challenges and Actions

Hospital bed availability, particularly in the intensive care units (ICU), has required cautious monitoring. At Lee Health, a drop in "other" admissions has contributed to sufficient hospital bed resources for management of COVID-19 patients. The same has been true for non-ICU beds.

Repurposing of many units to concentrate patients who are coronavirus positive or potentially exposed to the virus has been instituted at all of our hospital campuses. The object of such efforts is to improve efficiency and reduce exposure of patients and staff to potential infection and spread.

Staff: Challenges and Actions

While relatively few staff have been confirmed as being coronavirus positive, the impact of COVID-19 on staffing levels has been profound.

Significant drops in hospital volumes (driven largely by a reduction in surgeries and cardiac procedures) and substantial budgetary shortfalls resulted in the need for balancing of staffing needs/costs.

Extensive furloughs, an early retirement incentive plan, pay cuts for administration and physicians, and remote work when possible (including widespread use of telehealth visits) have been/are being used to accommodate.

As volumes returned, some challenges arose in relation to the availability of adequate and appropriate staff, although this has generally been managed relatively easily.

Quarantines due to infections and exposure created more troublesome staffing issues. Most contacts have been traced to sources outside of the hospital. Within our System facilities, employee exposure occurred primarily in common areas, particularly break rooms and especially at meal times (resulting in placement of major restrictions).

At one point, 18 staff members assigned to one of the hospital's cardiac catheterization laboratories were on quarantine, limiting operations and requiring shifting of personnel to provide emergency/STEMI coverage.

We learned that a system-wide response requires establishing a protocol to ensure immediate screening of employees and patients for coronavirus infection, rapid response by employee health services, and functional contact-tracing teams.

Stuff: Creative Solutions to Ensure Supply

Because of reductions in elective procedures, most equipment has remained easily available. A notable exception has been periodic challenge with a sufficient quantity of personal protective equipment (PPE) and concerns about ventilator availability.

PPE challenges have at times required adjustments in use protocols, but have not limited case volumes. Daily monitoring of PPE availability and creative efforts to find new sources of equipment have been combined with careful protocols (modified as needed)…including some use of telehealth rounding for subspecialists in selected high-risk areas.

Engagement of the local community in manufacturing (from homemade masks in local homes to repurposing of distilleries for hand sanitizer and repurposing local facilities to manufacture protective hoods) has alleviated some potential shortfalls.

Anticipated problems with an insufficient number of ventilators and stretchers have not yet materialized, possibly because of a reduction in both elective procedures and reduction in emergency admissions during peak outbreak.

Nonetheless, this continues to be a source of concern and a focus of monitoring.

Patients: The Impact of Delayed Care

The fear of contracting the coronavirus infection has led to a reduction in the number of patients seeking emergency medical care and elective care requiring hospitalization. National data confirm this reduction in hospitalizations during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among patients seeking care for acute myocardial infarction (MI).1,2

Worrisome is the trend toward worse outcomes in these patients. At the (previous) peak in COVID-19 cases, MI admissions at Lee Health were down 32% compared with 2019, stroke admissions down 19%, and heart failure admissions down 41%.

The long-term effect of delays or avoidance of needed care and hospitalizations on morbidity and mortality has yet to be determined. As this behavior unfolded, local and national efforts to encourage patients to seek appropriate care began through the media.

In Southwest Florida, this included efforts to educate the community about signs and symptoms that should not be ignored and to assure that it was safe to seek urgent health care.

The COVID-19 crisis has presented challenges throughout the world, particularly for health care systems. It is incumbent on clinical and administrative leaders to seek insight from experience, modify plans and behaviors, and plan for the next crisis. Imbedded in crisis is opportunity for learning and improvement.

References

- Gluckman TJ, Wilson MA, Chiu S, et al. Case rates, treatment approaches, and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Cardiol 2020;Aug. 7:[Epub ahead of print].

- Wessler BS, Kent DM, Konstam MA. Fear of coronavirus disease 2019—An emerging cardiac risk. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:981-2.

Clinical Topics: COVID-19 Hub, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Vascular Medicine, Chronic Angina

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Infections, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Pandemics, Quarantine, Hand Sanitizers, Leadership, Public Health, Stretchers, Personal Protective Equipment, ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction, Occupational Health Services, Motivation, Community-Institutional Relations

< Back to Listings