Cover Story | Takotsubo Syndrome: Expanding Insights, Unanswered Questions

Between 2% to 3% of all patients and 5% to 6% of all women who present with what looks like an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are actually suffering from a peculiar and reversible acute cardiac condition, not caused by epicardial coronary obstruction, called takotsubo syndrome (TTS).

TTS, also known as takotsubo cardiomyopathy, stress cardiomyopathy and "broken heart syndrome," is a reversible form of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction first recognized in Japan in 1990.1

The name "takotsubo" originates from the Japanese word for an octopus trap, which describes the shape of the LV when it balloons out during systole in the acute phase of the event. This distinct shape is visible during systolic imaging and has become the hallmark of the condition.

Since 2005, when the first major English language reports appeared, TTS has become a recognized condition worldwide, particularly affecting postmenopausal women. Improved clinical awareness and greater access to cardiac testing have led to an increase in the diagnosis of TTS.

On the Rise or Better Diagnosed?

While TTS mimics an ACS, it is not caused by coronary artery blockages. Instead, it is linked to a surge of stress hormones, particularly catecholamines like epinephrine, which overstimulate the heart and lead to its temporary dysfunction.

The condition can present as acute onset chest pain with dyspnea, biomarker elevations and ECG changes, making it challenging to distinguish from other ACS. In extreme cases, patients can present with severe LV dysfunction, cardiogenic shock or with life-threatening arrhythmias.

WHO TO SUSPECT? WITTSTEIN'S SIX CRITERIA

When assessing a patient who may have TTS, consider these six criteria. Keep in mind it's a syndrome, thus a compilation of these findings, he says. Not all need to be present, but after reviewing these, it should be clear whether it's TTS.

An identifiable trigger. About 70% or 80% of patients with TTS have an identifiable trigger, whereas MI is not typically associated with a clear precipitating event and an association with stressful events is considerably lower than with TTS. If there's a precipitating event or trigger, start thinking about TTS.

"Once we see the ballooning pattern on echo and query the patient, we'll hear about a triggering event," says Wittstein, noting it doesn't have to be an extreme emotional event. It could be a physical illness such as stroke, a bad pneumonia or a terrible asthma flare, or even a bad migraine headache which he's seen in several of his patients.

Biomarker elevation (Tn/CKMB or BNP/NTproBNP). Typically, with an MI, the more muscle injured, the higher the troponin spill into the blood. With TTS, there often appears to be a large amount of myocardium affected, but the troponins are only mildly elevated. If the heart looks worse than the troponin level would suggest, think TTS.

ECG abnormalities. No single ECG finding indicates TTS, but some are considered characteristic. One is diffuse ST-segment elevation on presentation, similar with STEMI. But there is reciprocal ST depression in patients with STEMI and this is less likely in TTS. It's a subtle finding, but one that jumps out to clinicians more experienced in diagnosing TTS. Other characteristic findings of TTS, not usually seen until 48 or 72 hours after the event, include the development of "deep, very ugly looking T-wave inversion" and prolongation of the QT interval.

Wall motion abnormalities (on echocardiography or left ventriculography). Any ballooning pattern is very suspicious for TTS, particularly if any of the other criteria are present. Of note, some large left anterior descending infarcts may look like ballooning, but there'd also be an occlusion and markedly increased troponin to suggest AMI rather than TTS.

While up to 80% of patients exhibit the classical apical ballooning pattern, atypical variants exist. Ballooning can be seen in the mid-ventricle, with hypokinesis in the mid-ventricle and hypercontractile apical and basal segments. And there's an inverted (reverse) or basal pattern seen in a small proportion of patients and a focal variant, characterized by hypokinesis or akinesis of an isolated segment, usually an anterolateral segment.

No culprit artery. Many patients with TTS have normal coronary arteries, but the presence of coronary atherosclerosis does not exclude the diagnosis. Essential in making the diagnosis of TTS is the absence of acute plaque rupture and thrombotic occlusion of the artery on coronary angiography. While the patient may have coronary atherosclerosis, the absence of acute coronary thrombosis is mandatory to diagnose TTS.

Recovery of LV function. This is critical. In survivors of TTS, the LV usually recovers within a few days to weeks. If the patient continues to have severe LV dysfunction several months after the event, likely it was not TTS and other etiologies for the cardiomyopathy should be considered. Importantly, the timing of the repeat echo influences the reported timing of the LV recovery. It may have recovered sooner than when it's identified on an echo performed at six months for example.

The data suggest that TTS is on the rise, but whether this represents a true increase in prevalence or primarily due to improved detection in the clinical cardiology community is debatable.

New findings from the International Takotsubo Registry (InterTAK) encompassing 3,957 patients diagnosed with TTS between 2004 and 2021 were presented during ESC Congress 2024 and simultaneously published in JACC.2 The largest global registry dedicated to TTS and headquartered in Zurich, InterTAK collects data from over 40 centers worldwide.

Researchers identified three key temporal trends in InterTAK: 1) a significant increase in the proportion of male patients, rising from 10% to 15% (p=0.003); 2) an increase in the diagnosis of midventricular TTS (from 18% to 28%), although apical ballooning remained the most prevalent form; and 3) an increase in the prevalence of physical triggers from 39% to 58% (p<0.001).

The authors also observed a significant increase in 60-day mortality, although this finding was no longer significant in a landmark analysis that excluded patients who died within the first 60 days. Causes of death were not reported.

According to Scott W. Sharkey, MD, FACC, "All of these findings reflect increased awareness of the syndrome among physicians – including a better understanding of physical triggers of the syndrome and an awareness of the wall motion variants beyond the well-known apical ballooning – and greater use of high-sensitivity troponin testing."

Sharkey is the chief medical officer for the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He has been conducting research on TTS for more than 20 years.

"Over time, we've come to realize that TTS is triggered by things other than emotional stress. Specifically, it's increasingly recognized in the hospital setting, triggered by a variety of acute noncardiac illnesses," he says. In this scenario, TTS is often discovered because of hypotension, acute heart failure, electrocardiographic T-wave inversion or troponin elevation, many times in the absence of chest pain. "For example, we'll see it in patients who undergo cholecystectomy for gallbladder sepsis and become hypotensive after surgery and, on echo, we see typical TTS wall motion abnormalities."

Indeed, while intense sympathetic activation and catecholamine flooding appear to play a central role in all TTS, acute episodes can either be triggered by sudden, unexpected emotional stress (primary TTS) or major physical illness or trauma (secondary TTS).

Emotional triggers include not just unexpected deaths and family arguments but also natural disasters and mass casualty events, or even happy events like weddings. However, TTS has also been shown to appear after a wide range of physical triggers, including stroke, seizure, brain injuries, sepsis, cancer, childbirth and operations.

Sharkey also suggests a link between the increased proportion of men with TTS and the increase in physical triggers: "In men, it takes a greater degree of stress for them to develop TTS making them more prone to experiencing it as a complication of a physical event, like an automobile accident or a stroke."

This also clarifies the increased mortality reported in InterTak because these individuals, mostly men, are succumbing from the primary triggering condition, rather than from TTS itself, he adds. Put another way, the findings support "an interesting and recurrent theme that has emerged in the takotsubo literature, and that is that groups with the lowest prevalence of TTS appear to be the sickest at the time of presentation," wrote Ilan S. Wittstein, MD, in a 2022 editorial.3

Time to Dig Deeper on Pathophysiology

While the newer registry data offers larger samples than previously available, several epidemiologic characteristics have remained surprisingly consistent, notes Wittstein in an interview with Cardiology.

"Twenty years ago, we saw that nine in 10 people presenting with TTS were women and most of them were between 65 and 75 years of age. We're seeing more or less the same now. There are more men diagnosed now, but that's more likely that we're better at seeing it, and not a real change in prevalence."

Wittstein, who serves as director of the Advanced Heart Failure Fellowship at Johns Hopkins Medicine, has written and lectured extensively on TTS.

"I think the more interesting discussion to have now is why are 85% or 90% of TTS patients women? And specifically older, postmenopausal women?"

The 30% of TTS patients for whom no trigger is identified is another perplexing question, adds Sharkey. "If the mechanism is stress-induced catecholamine release and they don't have stress, what is happening in these people? What do their catecholamine levels look like?"

Conversely, why do most individuals, all of whom experience a variety of emotional and physical stressors throughout their lives, not develop TTS?

Testing catecholamine levels in individuals suspected of having TTS would be convenient, but the test is challenging and expensive, making it not widely available. Nevertheless, Sharkey points out that several papers have documented cases of TTS occurring after catecholamine overdose.

"This strongly supports the exaggerated sympathetic activation and catecholamine hypothesis, as administering a drug like epinephrine can quickly lead to the development of TTS," Sharkey explains. The hypothesis itself is credited to Wittstein.

TTS gained international awareness when Wittstein and colleagues published their seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine describing a cohort of 19 individuals, all women, who presented with LV dysfunction after sudden emotional stress.4

Diffuse T-wave inversion and a prolonged QT interval were seen in most of the group and 17 of 19 patients had mildly elevated troponin I levels, but only one had angiographic evidence of clinically significant coronary disease. LV dysfunction was present on admission (median ejection fraction [EF], 0.20) but it rapidly resolved in all patients within two to four weeks.

Just nine days earlier, Sharkey and colleagues published a report in Circulation on 22 women who presented with "reversible cardiomyopathy triggered by psychologically stressful events," which can mimic evolving acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or coronary syndrome.5

Today, both clinicians readily acknowledge that the catecholamine surge is only one piece of a much larger puzzle and that a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of TTS is lacking, as are effective therapeutic strategies.

Also, while once thought to be a benign condition, recent studies have suggested that long-term mortality is higher than in the general population and resembles that seen with ACS.6

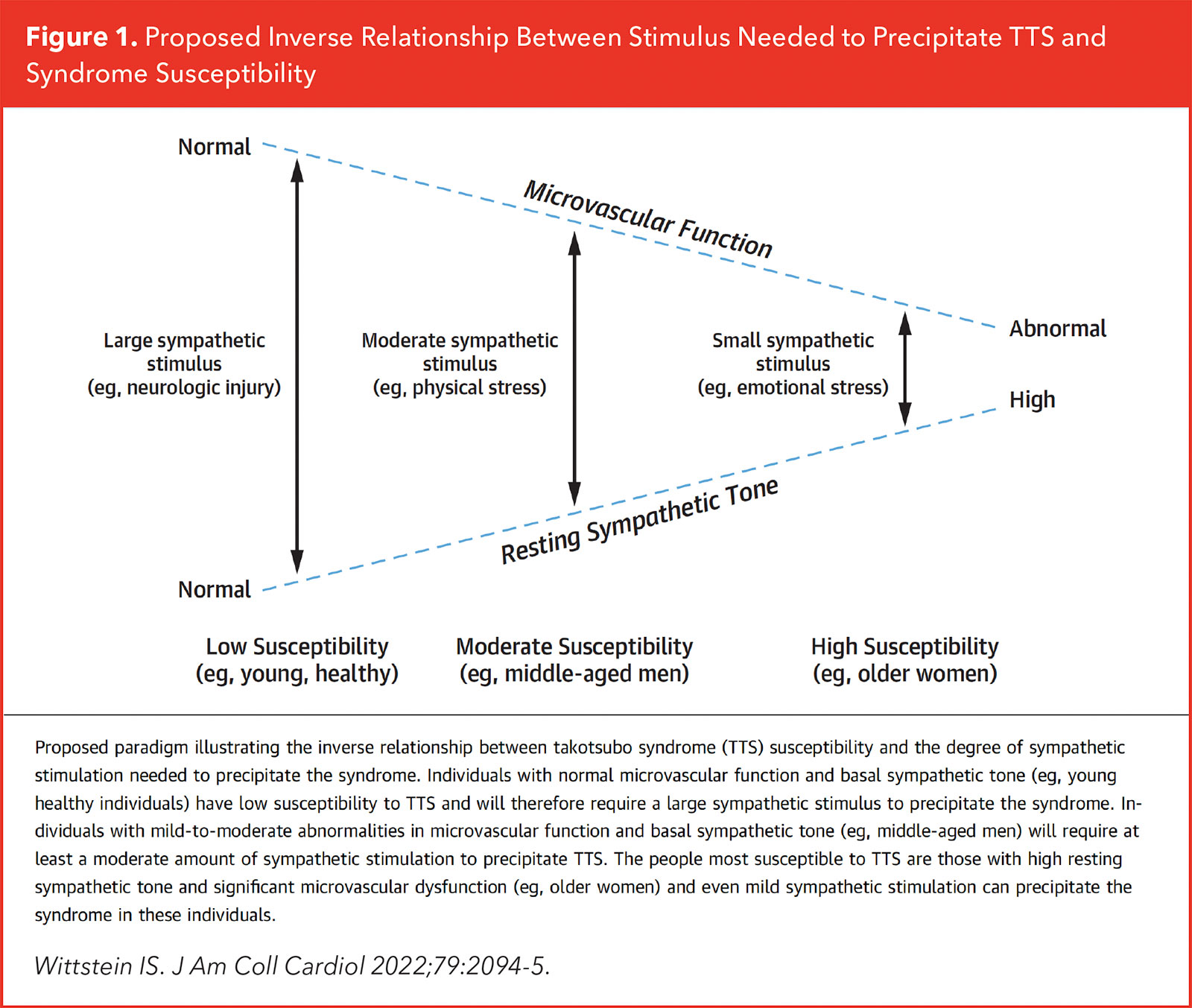

"Resting sympathetic nervous activity increases with age and is particularly elevated in women after menopause, while cardiac vagal tone and baroreflex sensitivity decrease," says Wittstein. Hormonal factors play a role and estrogen is also an important regulator of endothelial dysfunction and vasomotor tone (Figure 1).

"We think the risk of developing TTS may depend on a delicate balance between resting sympathetic tone and microvascular function, and the combination of these two things may render older women particularly susceptible to TTS during periods of acute stress and cardiac sympathetic activation," he says. Older, postmenopausal women populate that category: individuals with increased sympathetic tone and impaired microvascular function.

In contrast, the risk is low for young and healthy patients with normal sympathetic and vasomotor tone, therefore the prevalence is lower. The stimulus needed to precipitate TTS is much larger and is therefore more likely to be physical than emotional, he suggests.

Managing Survivors

In terms of how to manage survivors of TTS, young or old, women or men, well, that's pretty much anyone's guess. There are no randomized trials in TTS treatment or recurrence and there are no clear management guidelines. One of the two consensus statements published in 2018 are self-described as "a multinational crowdsourcing effort…"7-9

For most people, TTS is a one-time event. However, this is not the case for everyone. In the GEIST registry, including 749 patients from nine European centers, recurrence was reported in 4%.10 Other groups have reported recurrence in the 1% to 6% range.10

Just published in JACC: Advances, however, is a report from The Cedars-Sinai Smidt Heart Institute Takotsubo Registry and Proteomic Study showing a recurrence rate of 17%.11 Of the patients with at least one recurrent event, 3/15 (20%) had two recurrent events, and 2/15 (13%) had three recurrent events. Most with recurrence showed different patterns of wall motion abnormalities between events, and in 7/15 (47%) there were different trigger types (emotional, physical or no trigger identified) among their multiple events.

The authors found no difference between those with and without recurrence on psychosocial measures that assessed heart-focused anxiety, perceived stress, depression severity and childhood trauma.11

"We've seen that recurrence happens in about 5% to 10% of patients even if they're on a beta-blocker and an ACE inhibitor, which you would think should attenuate or block the sympathetic nervous system," says Sharkey.

Indeed, a 2024 network meta-analysis showed no significant reduction in recurrence rate of TTS with beta-blockers or ACEI/angiotensin receptor blockers, or their combination.12

And then there is the phenomenon of super recurrence. In 2023, Sharkey's group published their single-center, 21-year experience with super recurrence of TTS, which they defined as two or more TTS recurrences.13

A total of 506 patients with TTS were followed, with nine (1.8%) patients experiencing super recurrence. Those in the super recurrence group were younger and had higher peak troponin levels and lower EFs during initial TTS episodes than patients with one TTS event and at least 10 years of follow-up.

Emotional triggers were more frequent in the super recurrence group (65%) compared with the comparator group (53%) and a significant percentage of super recurrence patients also reported depression or anxiety (89% vs. 37% in those without recurrence).

Other findings included a lower nadir initial EF in the super recurrence group (25% vs. 35% in the comparator group; p=0.002) and higher peak troponin levels (2.08 ng/mL vs. 0.54 ng/mL; p=0.018).

Two of Sharkey's patients have had six recurrences of takotsubo, and two of Wittstein's have had eight.

Not known, says Sharkey, are the long-term consequences of recurrence. Although it appears mortality may be higher, it's not clear if that's related to noncardiac conditions or whether TTS might predispose patients to arrhythmias, conduction defects or even cardiomyopathy.

"My observation has been that most of my patients don't have an increase in other cardiac events outside of what age alone would bring," says Sharkey, noting he saw his first patient with TTS in 2003. "But this is something we really need to study more. It's disheartening to tell patients that we don't know how to prevent them from having a recurrent event."

Sharkey's Key Takeaways

Consider TTS in any admitted patient with acute illness and any hemodynamic instability, particularly if troponin is high or EKG changes are present. They may not have symptoms, particularly if sedated or ventilated, but could still have TTS.

Cardiogenic shock in TTS is not common, but it can happen. It's not nearly as lethal as in AMI. Even patients in profound shock can have complete recovery of LV function if properly supported over a day or two.

Many TTS patients are kept on beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors indefinitely, even after heart function has recovered. Recurrence is seen in both those taking and not taking beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors, so consider quality of life when deciding whether to maintain patients on these medications.

More than half of TTS is related to a physical stressor, not emotional. This is probably representative of better recognition, and it's important to keep in mind, particularly in acutely ill hospitalized patients.

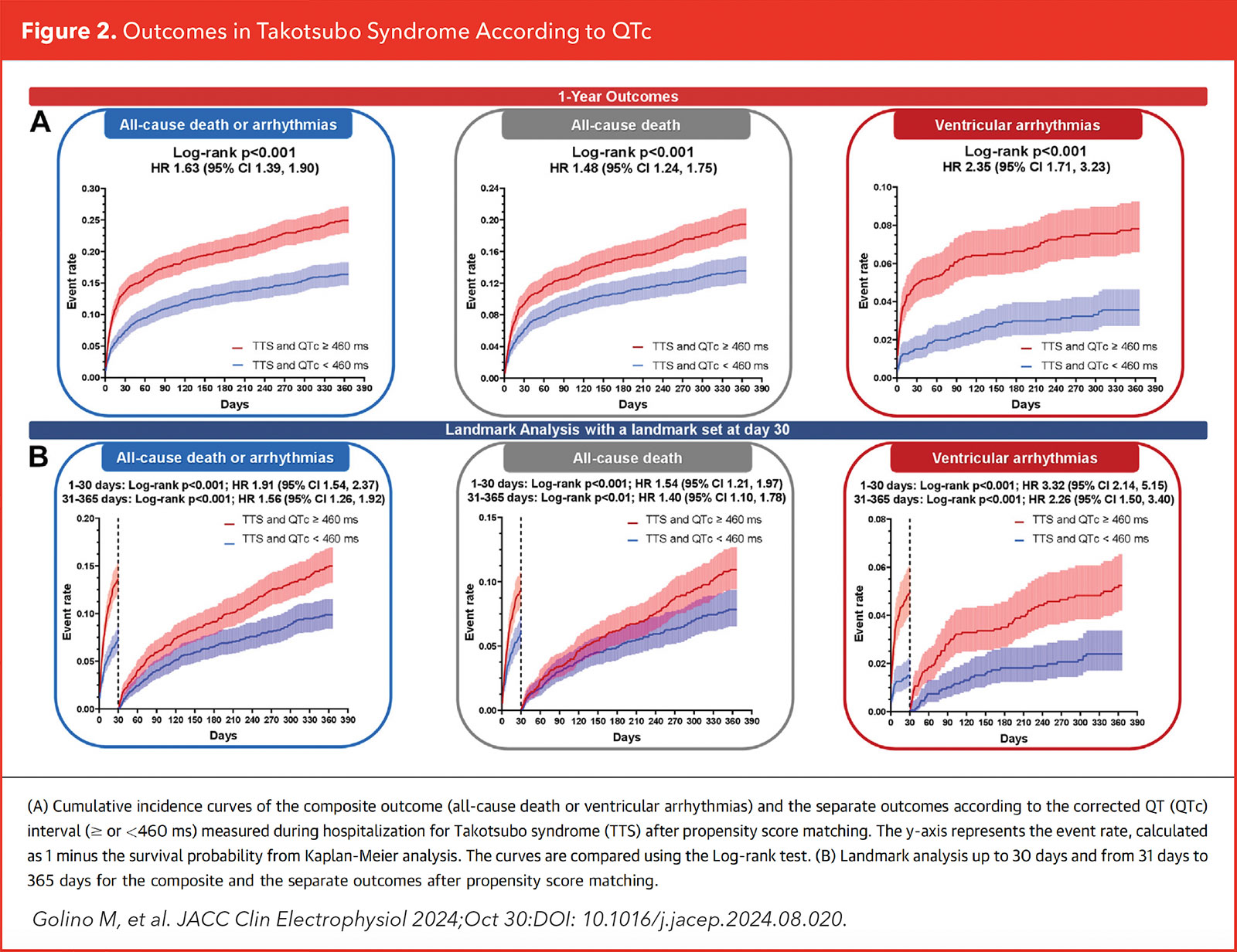

Repolarization injury and torsades de pointes (TdP) in TTS are poorly recognized. In a recent series, Sharkey's group identified 38 published TdP-TS cases, in which 80% of TdP events were within 48 hours of hospitalization, 90% occurred with QTc ≥500 ms, and 47.5% occurred with QTc ≥600 ms.1 "It's important to ensure patients aren't discharged with a very prolonged QTc or on medications that prolong the QTc," says Sharkey. "Document the QTc at discharge and consider outpatient monitoring. It will recover, but it can take longer to resolve than the contraction abnormality. The two are dissociated in time."

In a just-published analysis that included 5,390 patients with TTS, 67% had prolonged QTc (≥460 ms within 48 hours of hospital admission).2 After propensity score matching, those with prolonged QTc had significantly greater risk for all-cause death or arrythmias and the composite of the two outcomes (Figure 2A). A post hoc landmark analysis showed that prolonged QTc strongly predicted early and late events (Figure 2B).

References

- Vemmou E, Basala T, Witt D, et al. repolarization injury and occurrence of torsades de pointes during acute takotsubo syndrome. JACC Adv 2024;3: 101263.

- Golino M, Rodriguez-Miguelez P, Del Buono MG, et al. QT prolongation and 1-year outcomes in patients with takotsubo syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2024;Oct 30:DOI: 10.1016/j.jacep.2024.08.020.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Dote K, Sato H, Tateishi H, Uchida T, Ishihara M. Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasms: A review of 5 cases. J Cardiol 1991;21:203-14.

- Schweiger V, Cammann VL, Crisci G, et al. Temporal trends in takotsubo syndrome: Results from the International Takotsubo Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;84:1178-89.

- Wittstein IS. Why sex matters in Takotsubo syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:2094-96.

- Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JAC, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med 2005;352:539-48.

- Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, et al. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation 2005;111:472-9.

- Pelliccia F, Camici PG. Unraveling the mysteries surrounding Takotsubo Syndrome: Insights from a 30-year journey. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;84:1190-2.

- Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part I): Clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2032-46.

- Dias A, Núñez Gil IJ, Santoro F, et al. Takotsubo syndrome: State-of-the-art review by an expert panel - Part 1. Cardiovasc Revascularization Med Mol Interv 2019;20:70-9.

- Dias A, Núñez Gil IJ, Santoro F, et al. Takotsubo syndrome: State-of-the-art review by an expert panel - Part 2. Cardiovasc Revascularization Med Mol Interv 2019;20:153-66.

- El-Battrawy I, Santoro F, Stiermaier T, et al. Incidence and clinical impact of recurrent Takotsubo syndrome: Results from the GEIST registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e010753.

- Marano P, Maughan J, Obrutu O, et al. Evaluation of recurrent takotsubo syndrome. JACC Adv 2024;3:101247.

- Santoro F, Sharkey S, Citro R, et al. Beta-blockers and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors for takotsubo syndrome recurrence: A network meta-analysis. Heart 2024;110:476-81.

- Shaw KE, Lund PG, Witt D, et al. Super recurrence of takotsubo syndrome: Clinical characteristics and late cardiac outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis 2023;12:e029144.

Clinical Topics: Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Heart Failure, Hypotension, Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy