Get to Know Your Leaders | Filling the Pipeline: Innovative Programs Aim to Expand Diversity in Medicine and Cardiology

If you want to increase diversity in the cardiology workforce, you have to start young. Think elementary school age. That's what the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in New York is doing with its Healthy Living Long Island program. There, medical students visit students at local elementary schools to not only teach them about healthy eating and exercise, but about careers in health care.

The medical students "open the door to show this is a possibility," says Robert O. Roswell, MD, FACC, associate dean for Diversity and Inclusion and associate professor of Cardiology and Science Education at Zucker.

Robert O. Roswell, MD, FACC

Robert O. Roswell, MD, FACC

"Everyone who is looking to diversify the medical workforce has to realize that we have to go back further and further (in students' lives) to expose them to the field," he says.

The Healthy Living Long Island program is just one of several initiatives Roswell oversees as part of Hofstra's efforts to nudge minorities, women and other diverse groups into the medical professions.

The efforts are needed. In 2018, just 4 percent of the 2,917 cardiology residents in the U.S. were black and just 4.8 percent were Hispanic. And while half of all medical students are women, just one in four continues on to a cardiology residency.1

To address such disparities, in 2017 the ACC created a Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion. Its mission is to identify opportunities to increase diversity and inclusion in cardiovascular medicine. One objective calls for engaging and leveraging "all available talent by attracting and providing value to underrepresented groups in cardiology across the 'career life-span.'"2

Which means starting long before a student takes the MCAT.

Diverse Programs Needed For a Diverse Workforce

Roswell wouldn't be where he is today, he says, without a program called Gateway to Medicine, which was offered at his Brooklyn high school. The program, still in effect today, is designed to recruit and train physicians from underserved minority populations and encourage new doctors to work in communities most in need.

"Before I went into that program, I wasn't sure if I wanted to go into medicine," he says. "I excelled in science, but I also thought of getting a PhD in mathematics, statistics or biology. I hadn't had enough exposure to medicine to even consider it as a career option at that point."

So he personally understands the importance of the programs he currently oversees. In addition to the Healthy Living elementary school initiative, Hofstra offers three other programs to steer underrepresented students into medicine.

- Medical Scholars Pipeline Program. This program was created in 2010 to provide an educational pathway for rising high school juniors and seniors, and rising college freshman, who are underrepresented in medicine. Students are exposed to a variety of health care career paths, but also receive college prep, leadership and mentoring training from health care professionals at the medical school and Northwell Health.

Since it began, 194 students have enrolled in the three-year program and 100 students have completed it, with 18 former students enrolling in professional health care programs. - Medical Science Youth Program. This partnership between Nassau Community College and Zucker provides seventh and eighth graders in schools with a 50 percent or higher poverty level with information about medical careers. The goal is to develop meaningful mentorships and educational opportunities designed to enhance academic success and foster an interest in a career in medicine.

- The Zucker Pipeline Program. The medical school's newest initiative, this is a three-year program beginning in the student's sophomore year that is designed to offer a pathway to matriculation to the medical school. "Our hope is that by giving them decent exposure and intensive training they will matriculate into our medical school or medical school in general," says Roswell. The first cohort is just now finishing its first year.

Numerous studies find that such pipeline programs are successful at steering underrepresented students into the health professions as well as improving their academic performance in high school, college and graduate school.3

Paying it Forward

Heval Mohamed Kelli, MD

Heval Mohamed Kelli, MD

When Heval Mohamed Kelli, MD, a cardiology fellow at Emory University in Atlanta, GA, spoke at his old high school in 2016 about his journey from Syrian refugee and dishwasher to cardiologist, he was inundated with emails from students sharing their own stories and challenges.

"One common feedback was that they were inspired by my presence in their community, that it made them feel that someone cared, and that they can believe in themselves to be doctors," he says.

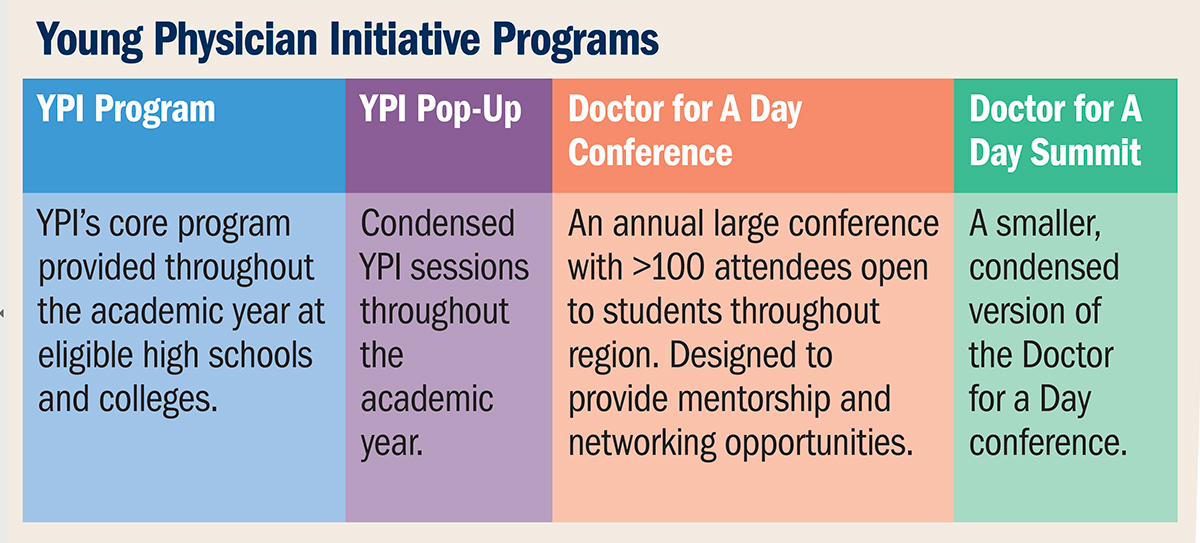

That same year, Kelli founded the Young Physician Initiative (YPI), part of the nonprofit U-Beyond Mentorship (ACC is also a partner). Its goal is to provide early and interactive guidance to underserved high school and college students who are interested in medicine.

Kazeen Nuri Abdullah, MD

Kazeen Nuri Abdullah, MD

Kazeen Nuri Abdullah, MD, an Associate Fellow of the ACC, is also an integral part of the YPI, where she mentors young girls to go into medicine and cardiology. A Kurdish refugee, like her husband Kelli she's committed to investing in the community and shaping future generations of cardiologists.

The Initiative started with just Kelli and one medical student. Today, it boasts four programs that reach 80 to 100 students a month, more than half of them minorities and women, in four high schools and four colleges throughout Georgia. "My goal is to create simple, sustainable and replicable programs that will inspire students into medicine," Kelli says.

"It's great when a student shadows a physician, but that stops when they stop doing it," he says. Yet the key to success, as he learned himself, is long-term mentoring and access to a medical network, something that just isn't available in underserved communities. He was lucky, he shares. "I met a doctor who guided me in the process and then met others through that network." The formal pipeline programs of YPI, he says, are designed to take the luck out of the process.

But, he stresses, "the medical students drive the efforts to run the program and inspire the students."

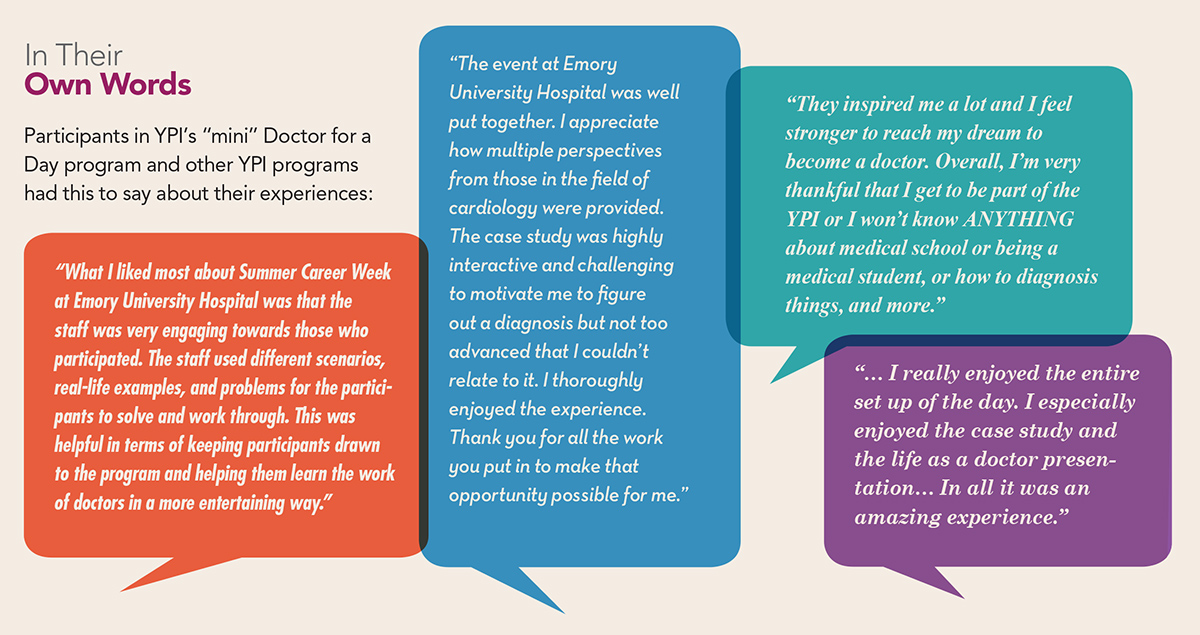

The newest YPI program is what Kelli calls a "mini" version of its annual Doctor for a Day summit. Held in conjunction with the ACC's Diversity and Inclusion Committee and the POSSE Foundation, the two-hour sessions provide a small-group experience for no more than 30 students to learn about cardiology.

At a recent session, Ozlem Bilen, MD, a female cardiology fellow gave a presentation about what it means to be a woman and mother in cardiology, while Sahar Ismail, MD, an interventional fellow, brought in catheters and other equipment to explain his job. "The whole purpose is to inspire students and provide exposure and create a model that can replicated across the state," Kelli says. Students also discuss a specific case, including its diagnosis and management.

Kelli has big plans for YPI, including:

- Expanding the model to other cities and states, particularly rural areas.

- Providing tool kits to ACC chapters throughout the country.

- Building a model for middle schools to expand on the deep pipeline efforts.

- Partnering with local clinics and hospitals to enable students to shadow health professionals in the clinical setting.

And Kelli would like to hear from other ACC chapters interested in spreading the word. "I'm open to partner and share our models with anyone who is interested in the efforts of diversity and inclusion," he says.

YPI Results... By the Numbers

Since the YPI began three years ago, it has reached more than 350 students. Post-program surveys show that:

- 61 percent had no formal exposure to medical experiences prior to YPI

- 85 percent became interested in becoming a doctor after attending a program

- 91 percent became interested in medicine to treat and help others

- 95 percent gained understanding of the process of becoming a doctor

- 100 percent would recommend the program to friends and classmates

- 100 percent had family support to become a doctor

Do Your Homework

The most important component to a successful pipeline program is understanding the needs of students in the catchment area, says Roswell. "Is it exposure to other experiences? Shadowing? Volunteering? Community services? Or it is just mentorship and guidance?" he asks. "You have to hone in on that and figure out what the needs are and fill in the gaps." That's why he recommends medical schools complete a needs assessment to see what is missing in their area and target opportunities to improve matriculation.

"You have to be very strategic to identify how you want to diversify your work force and then set that as the objective at the different stages of pipeline programs." In addition, he says, "each level of the pipeline programs should have different goals and objectives for the different levels of students that are participating."

It's also important to understand that diversity is not just racial, ethnic or gender, Roswell says. It's also socioeconomic and geographic such as rural vs. urban. "There are many ways of defining diversity."

Grassroots Efforts Beginning to Grow

The two programs highlighted here are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg when it comes to how ACC chapters are working to encourage students – whether high school, undergrad, medical school or residency – to consider cardiology as a career.

For instance, the New Mexico chapter helped create a group for medical students at the University of New Mexico who are interested in cardiology and want to learn more. "What we're trying to do through the university is cultivate their interest," says Paul Andre, MD, a cardiology fellow and ACC chapter member. "We're providing advice on choosing a specialty; getting into residency programs; and what it means to be a cardiologist." The group has about 30 students and is, Andre says, "very diverse."

The group, which has formal recognition and funding from the University of New Mexico, also ran a Camp Cardiac last summer for high school students interested in a career in cardiology. The ACC Washington chapter is also starting an outreach program, this one for high school students from underrepresented minority groups.

"Our plan is to have high school students attend our annual meeting this fall to expose them to our profession through live demonstrations and talks by our members," says Eugene Yang, MD, FACC, governor of the ACC Washington Chapter. "We also plan to pilot a year-long mentorship program for these students and pair them with chapter members so they remain engaged."

Does your chapter have any outreach activities? Let us know! Share your story using @ACCinTouch and the hashtag #CardiologyMag.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Cohort Studies, Fellowships and Scholarships, Electronic Mail, Goals, Hispanic Americans, Internship and Residency, Leadership, Mentors, Minority Groups, Needs Assessment, Physicians, Refugees, Schools, Medical, Social Responsibility, Social Welfare, Students, Medical, Universities

< Back to Listings