Has Employment of Cardiologists Been a Successful Strategy? – Part 1

Only 15 years ago, the landscape of cardiology practices was much different. Back then, aside from a few notable exceptions such as the Minneapolis Heart Institute and academic programs, almost all cardiologists were part of independent practices.

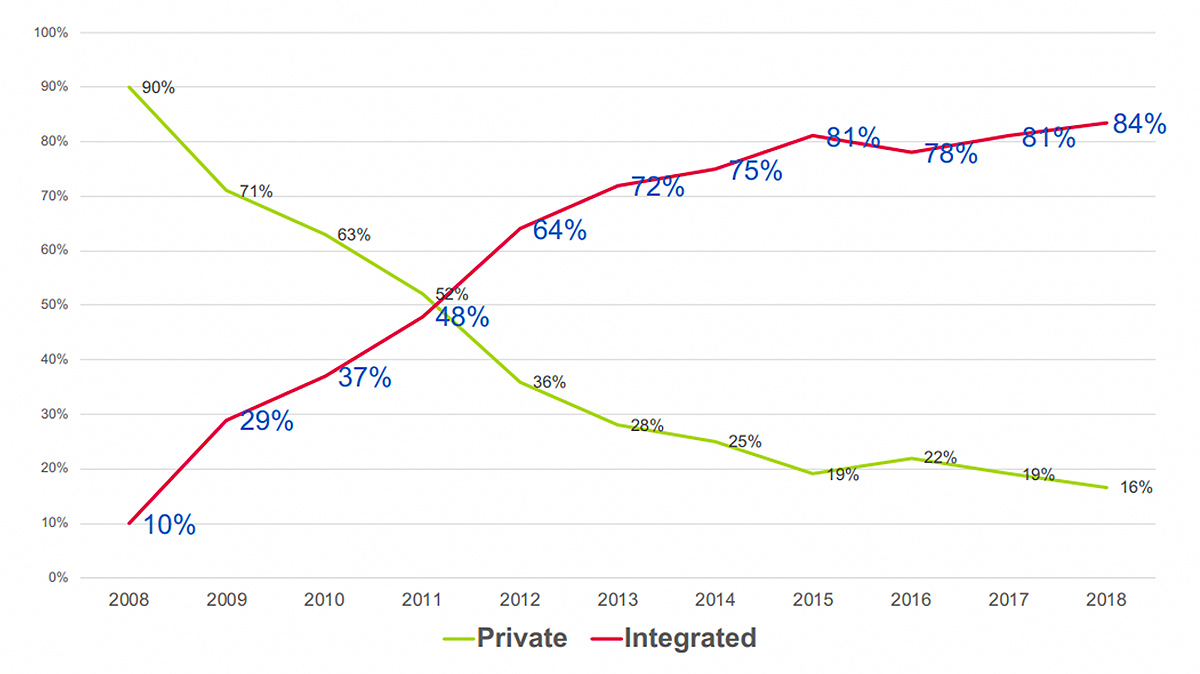

Fast forward to 2019 and the landscape is dramatically different, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Today, analyses by a number of organizations including the ACC and MedAxiom suggest that more than 70 percent of cardiologists are employed by hospitals or health systems. This scale of physicians moving from independent to employed practices has not been seen since the late 1980s and early 1990s, as the Clinton administration proposed sweeping delivery system reforms designed to merge hospital and physician spheres into integrated delivery networks, known then as "Regional Accountable Health Plans."

During that time period, physician practice ownership fell 14.4 percent, from 72.1 percent in 1988 to 57.7 percent in 1994, due to the emphasis on managed care and the desire by hospitals and health systems to gobble up and control the primary care physicians who were seen as key gatekeepers of large patient populations.

This recent wave of cardiologists moving en masse to hospital employment raises the question: has this been a successful phenomenon and good for patients, cardiologists and their employers? Let's explore this question from a variety of viewpoints, starting with some background on what drove this change in the first place.

With the 2005 budget reconciliation law, known as the Deficit Reduction Act, Congress dramatically reduced what Medicare paid for office-based cardiac imaging compared to rates paid to hospitals for the same services. Furthermore, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) eliminated lucrative consultation codes and replaced them with lower-reimbursed evaluation and management codes.

Compounding these changes was the bundling of payments for some cardiovascular services. The result was a reduction of around 40 percent of cardiologists' overall private practice reimbursement.

A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association looked at a random sample of 5 percent of Medicare fee-for-service claims between 1999 and 2015. The authors estimated the extra costs of moving cardiovascular testing from physician office settings to hospital settings (mostly due to the wave of employing cardiologists) totaled an extra $661 million in 2015 in Medicare payments, including $161 million in increased patient out-of-pocket costs.

The reason CMS seemingly targeted private physician practices, as compared to hospitals, is often attributed to a large increase in noninvasive cardiac testing between 1999 and 2005, and causes one to wonder if the overall intention was to drive cardiologists to become employed.

However, many believe that the movement of formerly private practitioners to hospital employment was conceptually appealing to policymakers because it seemingly dilutes physicians' incentive to render more services than patients need. Whether that actually drove the reimbursement changes is unknown.

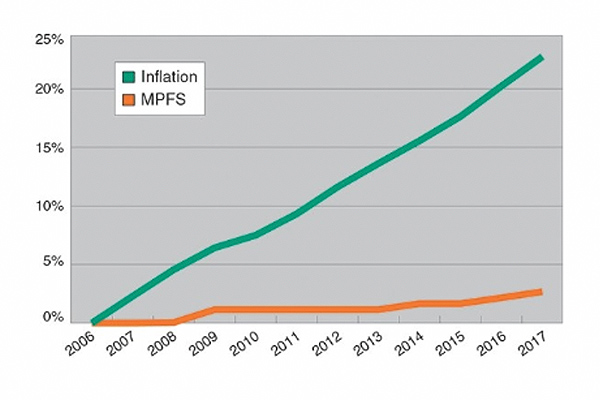

The graph below illustrates how private practice reimbursement (the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule [MPFS]) has compared to inflation over time. It is important to note that the MPFS has been the only major component of CMS reimbursement that has been subjected to minimal, and sometimes negative, annual fee adjustments since 2006 while not keeping up with inflation. Conversely, hospitals during this same time period have received regular reimbursement increases.

These reimbursement pressures – combined with rising overhead costs; need for capital to fund equipment replacement; entry into electronic health records; further anticipated cuts to professional fees and office-based reimbursement; and uncertainties with the Sustainable Growth Formula – created an agonizing dilemma for cardiologists from 2006-2009.

Do they make drastic changes to preserve their independent practices (including income reductions, staff reductions, service reductions and potentially negative lifestyle impacts) or do they align with a hospital or health system? Most often the chosen answer was alignment.

This is not to say that the decisions to align were solely motivated by practice finances. In truth, many cardiologists believed the potential benefits of alignment could bring the opportunity to participate in systemic changes that improved patient care coordination, take advantage of proposed "value-based" reimbursement as part of a larger health enterprise, accelerate access to emerging cardiac procedures and technologies, solidify referrals from previously employed primary care physicians, and gain greater input into the decisions involving the overall cardiovascular service line.

In addition, the mass movement among cardiologists to seek employment was also driven by the thought that it will be a shelter from the onslaught of coming regulations and administrative burdens – protecting valuable time spent with patients that was otherwise being spent on running an independent practice.

This explanation briefly describes the wave of cardiology practice transition from private practice to employment, which began taking off around 2007, peaked around 2011, and has slowly declined to groups who chose not to be in the early wave or ran out of better options.

Of course, some cardiology practices, ranging from small to very large, never opted for the employment route for a variety of reasons. The result is that an estimated 20 – 25 percent of cardiologists today remain in independent practices, albeit some in strong alignment with hospitals via Professional Service Agreements or other contractual models.

Disclaimer: The views or opinions presented in this document are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent those of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. The American College of Cardiology Foundation does not in any manner endorse, or guarantee the accuracy of any information included in, any documents created by a third party and linked to in this document. This document is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide legal advice; please consult with your own counsel for legal guidance on compliance with applicable laws and regulations. This document is not intended to and does not encourage any coordination between competitors with respect to employment or compensation practices. To comply with the antitrust laws, competitors should not discuss or agree on salaries or other compensation.