Has Employment of Cardiologists Been a Successful Strategy? – Part 2

Click here for Part 1 of this article.

Has the industry transformation to employed cardiologists been good or bad for patients?

In a 2016 New England Journal of Medicine catalyst article highlighting why health care mergers can be good for patients, the authors made many points and provided examples about how alignment between physicians and hospitals or health systems can reduce unwarranted variation and eliminate redundant costs.

A more cardiology-specific example of the patient benefits of alignment speaks to how consolidation can increase access to new cardiac technologies and access to services in locations that otherwise would not soon have it.

However, a literature search for evidence-based studies showing the benefits of physician-hospital alignment found very limited examples, and most focus on how to make alignment work rather than tout successes. Instead, there were far greater demonstrations about why alignment has not been good for patients.

For example, a 2017 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine examined the changes in hospital-physician affiliations in U.S. hospitals and their effect on quality of care. This retrospective cohort study of U.S. acute care hospitals between 2003 and 2012 examined risk-adjusted hospital-level mortality rates, 30-day readmission rates, length of stay and patient satisfaction scores for common medical conditions.

The study examined performance up to two years after evidence of switching to an employment model. The authors concluded that up to two years after conversion, no association was found between switching to an employment model and improvement in any of four primary composite quality metrics. The study concluded that physician employment alone probably is not a sufficient tool for improving patient care.

Another study, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, found that financial integration between physicians and hospitals raises patient spending, but not care quality. It recommended that, given the higher spending incurred in such consolidations, policy makers should carefully consider policies that limit consolidation of hospitals and physicians.

Additional arguments against the notion of consolidations being good for patients can be found in articles such as:

- Hospital Mergers Hurt Health Care Quality

- Vertical Integration in Health Care Doesn't Boost Care Quality

- Few Health Systems Positioned to Innovate Quickly

- The Hidden System That Explains How Your Doctor Makes Referrals

- If Your Longtime Doctor Moves Will You Lose That Physician Because of a Non-Compete Clause?

Collectively, these articles support the notion that alignment of physicians and hospitals – and amongst hospitals for that matter – have not delivered on measurably better quality, service or cost. In other words, there is no strong research showing that alignment has resulted in widespread improvement in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Triple Aim of patients seeing higher quality at a lower cost while enjoying a better patient experience.

While these articles focus on the generalities of all types of alignment, what can we conclude about the impact to cardiology patients? Possibly the most damning evidence can be found in recent data published in Journal of the American Medical Associaton (JAMA), Trends in Cardiometabolic Mortality in the United States, 1999 - 2017.

This exhaustive analysis demonstrated that heart disease mortality rates fell by 22 percent from 1999-2011 before increasing 4 percent from 2011-2017. While it would be inappropriate to solely correlate cardiology employment with this uptick in mortality rates, it does raise a question as to whether the originally lauded benefits of cardiologist alignment (improved care coordination, etc.) are actually being achieved.

The fact is that cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of mortality of U.S. adults and it appears unlikely that the strategic goals from the American Heart Association – a 20 percent reduction in mortality due to cardiovascular diseases by 2020 and improving the cardiovascular health of all Americans by 20 percent – will be achieved.

Considering that nearly half of U.S. adults are estimated to have heart disease, the need for successful strategies to care for patients with cardiovascular disease has never been greater.

Beyond the lack of evidence of widespread clinical benefits for cardiology patients, we also must accept that hospital buyouts of cardiology practices, which have turned independent practitioners into hospital employees, has led to higher spending by government and private insurers and higher out-of-pocket costs for patients.

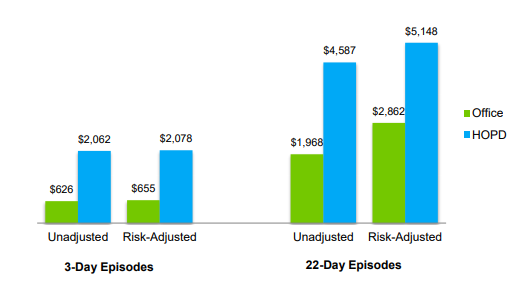

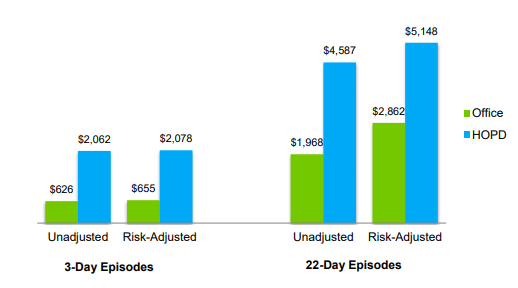

Health care services provided in hospital outpatient (HOPD) settings are reimbursed at higher rates than when provided in physician offices. For example, the same stress test can cost two to three times as much in the local hospital compared to a private practice in the same community.

This difference affects cost to Medicare and patient out-of-pocket costs. In a study by Avelere Health, for certain cardiology services, this results in up to 27 percent higher costs for Medicare and 21 percent higher for patients.

A study published in Journal of the American Medical Association showed that after adjusting for patient severity and other factors over the period, local hospital-owned physician organizations incurred expenditures per patient 10.3 percent higher than did physician-owned organizations.

Why is that? Physicians employed by hospitals perform a higher volume of services in HOPD settings than in physician offices. More specifically, these studies found that increased physician employment by hospitals caused Medicare costs for four health care services to rise $3.1 billion between 2012 and 2015, with beneficiaries facing $411 million more in financial responsibility for these services than they would have if they were performed in independent physicians' offices.

What causes this increase in costs? I believe there are four factors:

- For some procedures studied, employed physicians are more likely to perform services in a HOPD setting than independent physicians.

- When hospitals acquire physicians, pressures from the employer to control "leakage" causes referral patterns change and physicians are more likely to refer patients to higher-cost facilities within their employer's network, which potentially impedes competition from other hospitals.

- The combined leverage of the hospitals and employed physicians can lead to the ability to negotiate higher hospital and physician commercial insurance rates.

- If hospitals pursue the use of provider-based billing, patients may receive two charges on their bill – one for the hospital charge and one for a "facility" fee. This is because under Medicare rules, in addition to professional fees, hospitals can charge a Part B technical fee for the physician or diagnostic services – something a private practice cannot do.

There is not enough evidence to say that the large movement of cardiologists to employed practices has been beneficial to patients from a quality perspective. That is not to say that individual heart programs cannot demonstrate clear quality improvements in their local care system. However, there is clear evidence that the financial impact to patients has been largely negative, either through direct out-of-pocket costs or much higher government spending.

Disclaimer: The views or opinions presented in this document are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent those of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. The American College of Cardiology Foundation does not in any manner endorse, or guarantee the accuracy of any information included in, any documents created by a third party and linked to in this document. This document is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide legal advice; please consult with your own counsel for legal guidance on compliance with applicable laws and regulations. This document is not intended to and does not encourage any coordination between competitors with respect to employment or compensation practices. To comply with the antitrust laws, competitors should not discuss or agree on salaries or other compensation.