From the Starting Line | CVI 2019: Takeaways to Refine Our Practice

The third annual Cardiovascular Innovations (CVI) meeting in Denver, CO, was an exciting, interactive educational conference for coronary, peripheral and structural heart disease.

It certainly met its goal of providing an overview of fundamental knowledge and technical skills for interventional cardiology and a synopsis of emerging, innovative practices.

This year I was honored to be invited as a member of the faculty. Here are my top takeaways from the meeting.

Coronary Intervention: Advances in Shock, RV Failure, Cardiac Arrest

Cardiogenic shock is the most common cause of death in patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction. In clinical practice, a useful tool is the recently published 2019 SCAI Cardiogenic Shock classification.

Each stage is described by physical exam and biochemical and hemodynamic markers: stage A (at risk), stage B (beginning), stage C (classic), stage D (deteriorating) and stage E (extremis). A cardiac arrest modifier (– [A]) is provided within the schema to identify patients with cardiac arrest regardless of its duration.1

Key Take Home Messages

- Get familiar with the 2019 SCAI cardiogenic shock five stage classification and appropriate management strategies.

- Clinical trials are ongoing for transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions.

- Early recognition of interventional complications and familiarity with bail-out techniques is crucial.

- Great things can be accomplished when we collaborate with people with similar goals and interests and it can be done in a way that contributes to the professional development of others.

In right ventricular (RV) failure, the critical importance of assessment of hemodynamics was reinforced, along with parameters such as cardiac power output and pulmonary artery pulsatility index, to best determine need for RV mechanical support.

Also highlighted was the role of extracorporeal cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (eCPR) for refractory ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest of a suspected reversible cause. Interestingly, two institutions – Ohio State University and University of Washington Medical Center – shared lessons learned when developing and implementing an eCPR program.

Adequate continuous CPR with automated CPR devices and predefined patient selection criteria were identified as key factors for success. The importance of a multidisciplinary team and system-based protocols were also noted.

Structural Heart Disease: Advances in TR Management

The focus on tricuspid regurgitation (TR) within the structural track provided a useful review of current and emerging trends in its management. The majority of TR is secondary to left-sided heart disease and/or pulmonary hypertension (functional TR). Primary TR is less common.

Echocardiography, computed tomography and MRI play a role in tricuspid valve evaluation and determining the appropriate timing for tricuspid valve therapeutics. Key echocardiographic criteria we should recognize include: qualitative (valve morphology, right chamber and inferior vena cava dilation, color-flow and continuous-wave Doppler); semi-quantitative (hepatic vein systolic flow reversal) and quantitative criteria (regurgitant orifice area and volume).2

Medical therapy includes treating the underlying primary etiology, heart failure symptoms and/or pulmonary hypertension when present. Current indications for surgical repair or replacement for TR are outlined in the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease.

The aim of transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions is to modify the tricuspid valve annular geometry or improve leaflet coaptation. These interventions include leaflet repair, annuloplasty, as well as vena caval and coaptation device implantation.

One-year outcomes of the Edwards FORMA spacer U.S. Early Feasibility Study were presented. This is a tricuspid transcatheter repair system which treats severe functional TR by implanting a spacer device as a new surface for leaflet coaptation.

The data presented revealed a persistent reduction in TR and improvement in 6-minute walk distance in the majority of treated patients. The study is currently paused as ongoing device improvements are needed to improve safety and reduce the risk of anchor dislodgment.

Complications: Prevention, Recognition, Management

Complications can occur despite adherence to best practices and techniques. Emotional intelligence in the face of complications and familiarity with bail-out strategies are important for the interventional cardiologist. Among these bail-out strategies are the use of balloon inflation and covered stents and coils for coronary artery perforation.

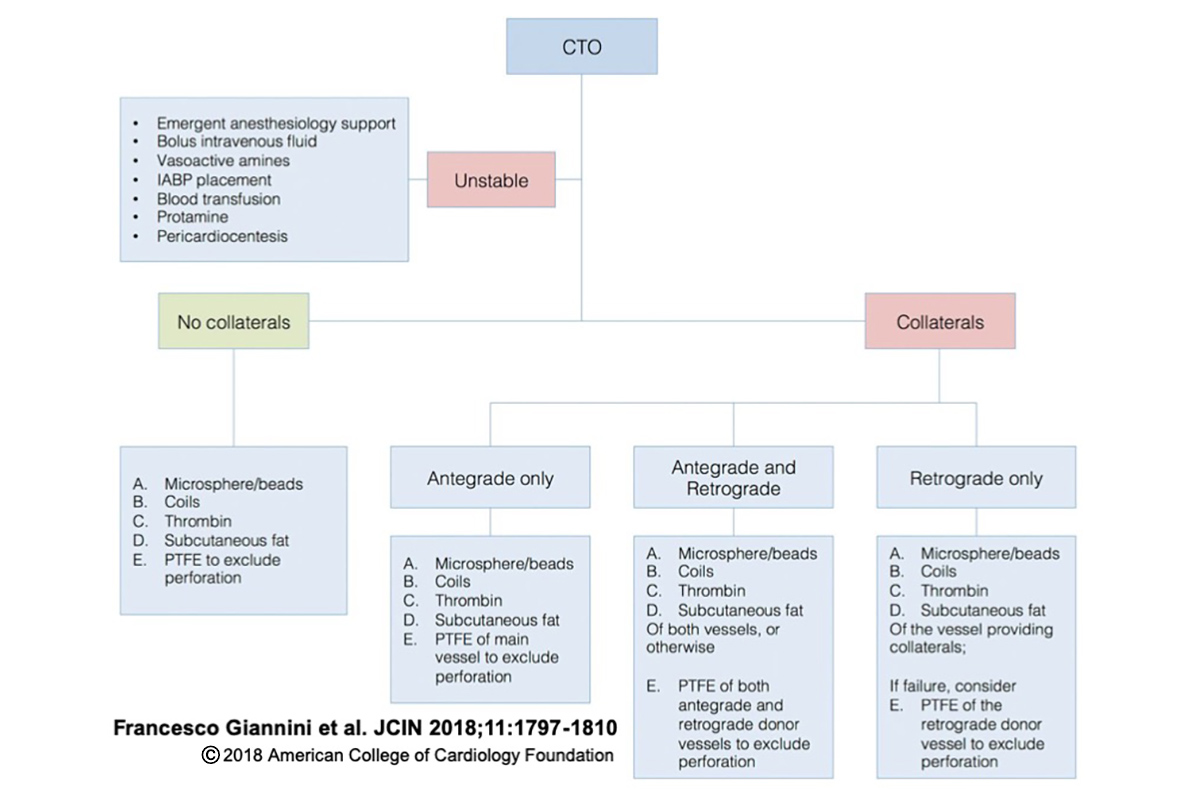

A live case of chronic total occlusion (CTO) that was complicated by a coronary collateral perforation reinforced for me the importance of scrutinizing for potential complications. In this case, the placement of coils led to successful treatment of the perforation. Giannini et al., provide a stepwise management approach for CTO perforation.3

A nonclinical takeaway is the reminder that great things can be accomplished through collaboration. CVI is the work of four friends with a burning passion for education in peripheral, coronary and structural heart disease: Subhash Banerjee, MD, FACC; Emmanouil Brilakis, MD, FACC; Mehdi Shishehbor, MD, FACC; and Paul Sorajja, MD, FACC. They're also committed to a diverse and inclusive faculty, with a focus on early- and mid-career professional development.

I urge my early career colleagues to remember that smaller cardiovascular meetings are a great resource to gain faculty experience at national or regional cardiovascular meetings. Use the ACC Member Hub (MemberHub.ACC.org) to network with individuals with similar interests and identify such opportunities.

CTO Perforation In the absence of collaterals, the lesion can be managed with microsphere or beads, endovascular coils, local thrombin injection, or subcutaneous fat embolization. If the affected vessel receives collateral circulation, we should distinguish anterograde versus retrograde collateral flow. Vessels receiving only anterograde or retrograde collateral flow should be managed with microsphere or beads, endovascular coils, local thrombin injection, subcutaneous fat embolization, or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent deployment of the donor branches to exclude the perforated vessel. Perforations of vessels receiving both anterograde and retrograde collaterals should be treated by intervention of both anterograde and retrograde donor vessels to exclude the affected branch. CTO = chronic total occlusion; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump.

References

- Baran DA, Grines CL, Bailey S, et al. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019;94:29-37.

- Taramasso M, Gavazzoni M, Pozzoli A, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:605-21.

- Giannini F, Candilio L, Mitomo S, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018;11:1797-1810.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Vascular Medicine, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Acute Heart Failure, Mechanical Circulatory Support, Pulmonary Hypertension, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Echocardiography/Ultrasound, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Hypertension

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Tricuspid Valve, Tricuspid Valve Insufficiency, Shock, Cardiogenic, Goals, Pulmonary Artery, Vena Cava, Inferior, Collateral Circulation, Patient Selection, Feasibility Studies, Microspheres, Coronary Vessels, Hepatic Veins, Ventricular Fibrillation, Echocardiography, Echocardiography, Heart Failure, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, Hypertension, Pulmonary, Intra-Aortic Balloon Pumping, Hemodynamics, Polytetrafluoroethylene, Heart Arrest, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Stents, Tachycardia, Ventricular, Subcutaneous Fat, Patient Care Team, Tomography, Emotional Intelligence, Cause of Death, Faculty

< Back to Listings