From the Starting Line | Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: A Primer for the General Cardiologist

"Doctor, what is SCAD?"

She was a 39-year-old multiparous woman admitted for evaluation of chest pain that began while watching television. Chest pain was described as moderate intensity, substernal chest pressure, worse with exertion. No recent fevers, chills, diarrhea or social stressors. She had no risk coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors and no family history of early CAD. On admission, her vitals were stable.

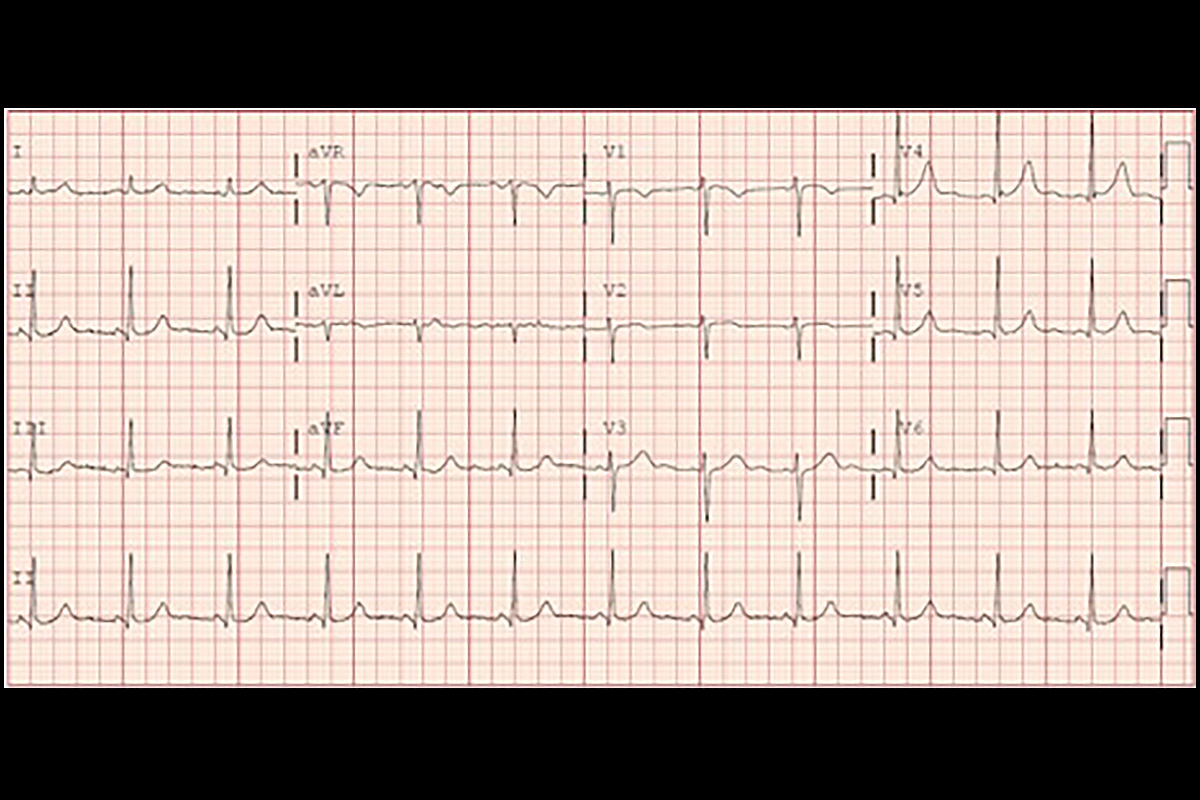

Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm with no ST-T changes concerning for ischemia. Laboratory results revealed elevated troponin level. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular (LV) systolic function, normal LV wall motion and no significant valvular disease. Her chest pain resolved with sublingual nitroglycerin.

I informed her that I was concerned she had SCAD (spontaneous coronary artery dissection) and recommended a coronary angiogram. My patient and the nurse were both surprised as neither had heard of the term "SCAD."

Definition, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology

SCAD is a nonatherosclerotic cause of acute coronary syndrome and sudden cardiac death. SCAD is defined as a noniatrogenic, nontraumatic dissection of an epicardial coronary artery and/or intramural hematoma formation, which leads to partial or complete occlusion of the coronary artery.1,2

SCAD predominantly affects pre- and perimenopausal women, and is a common cause of myocardial infarction in pregnancy and the postpartum period. The mean age for SCAD in women is reported as between 42 and 53 years.

Predisposing risk factors include fibromuscular dysplasia, female sex and connective tissue disease. Intense emotional stress, intense physical exertion especially Valsalva activities and hormonal fluctuations are associated with SCAD.

SCAD is characterized by the spontaneous development of an intramural hematoma within the coronary artery wall, which constricts the true lumen causing myocardial ischemia and/or infarction. Intimal dissection may be present.

Two mechanisms have been proposed for the pathophysiology of SCAD.3,4 The first mechanistic hypothesis involves intimal tear and media dissection with the creation of a false lumen.

The second involves media dissection, hematoma formation and luminal compression but no intima tear. In the second mechanism, it is hypothesized that arterial bleeding occurs within the vaso vasorum leading to intramural hemorrhage and subsequent luminal compression.

It is suggested that in some cases, the large intramural hematoma ruptures into the true lumen. The left anterior descending (LAD) artery is the most commonly affected coronary artery in SCAD.

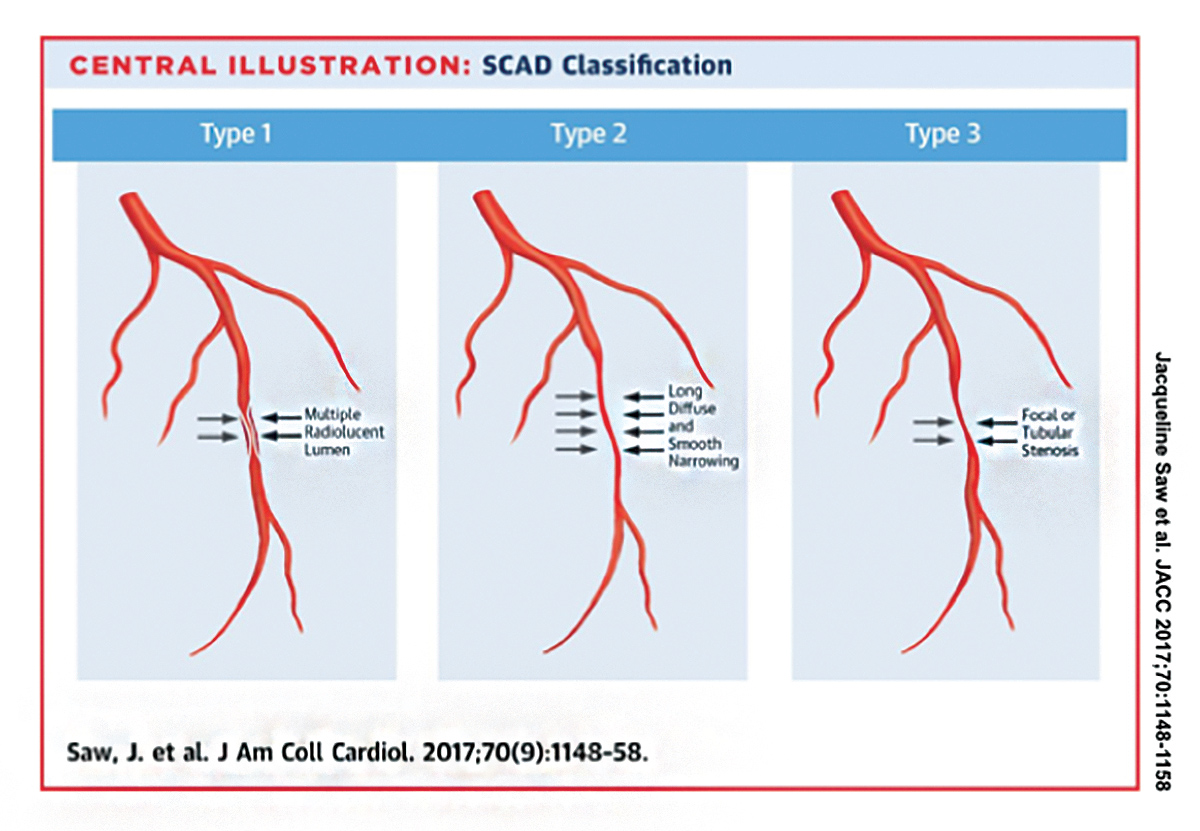

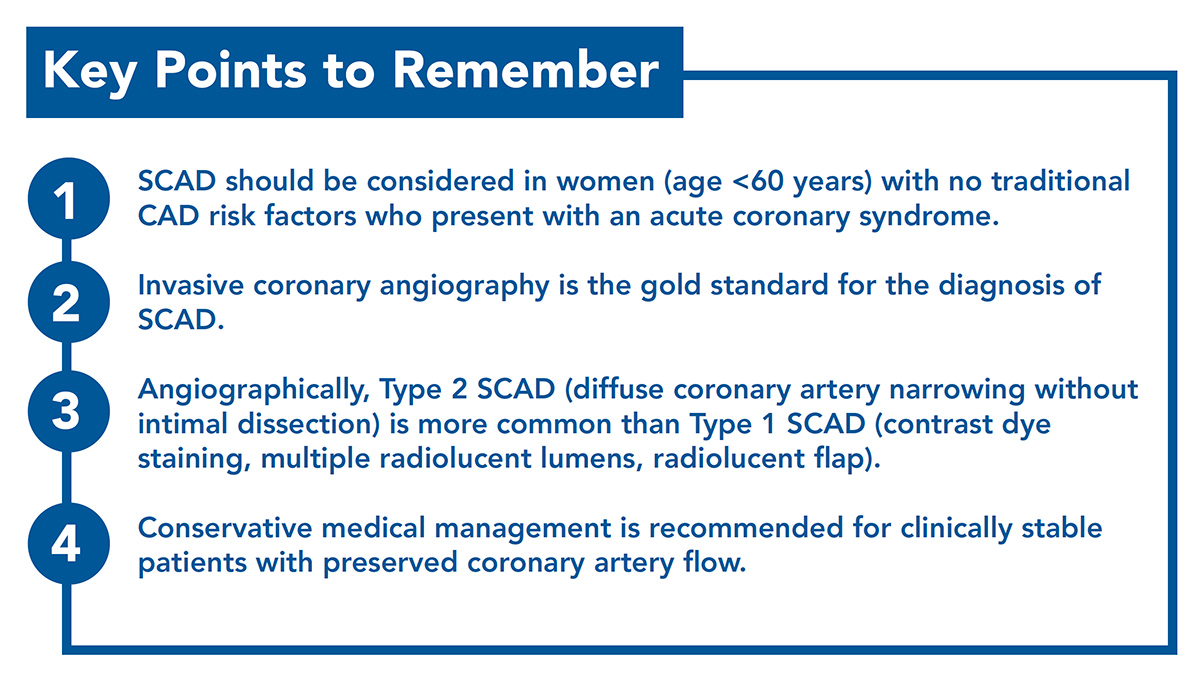

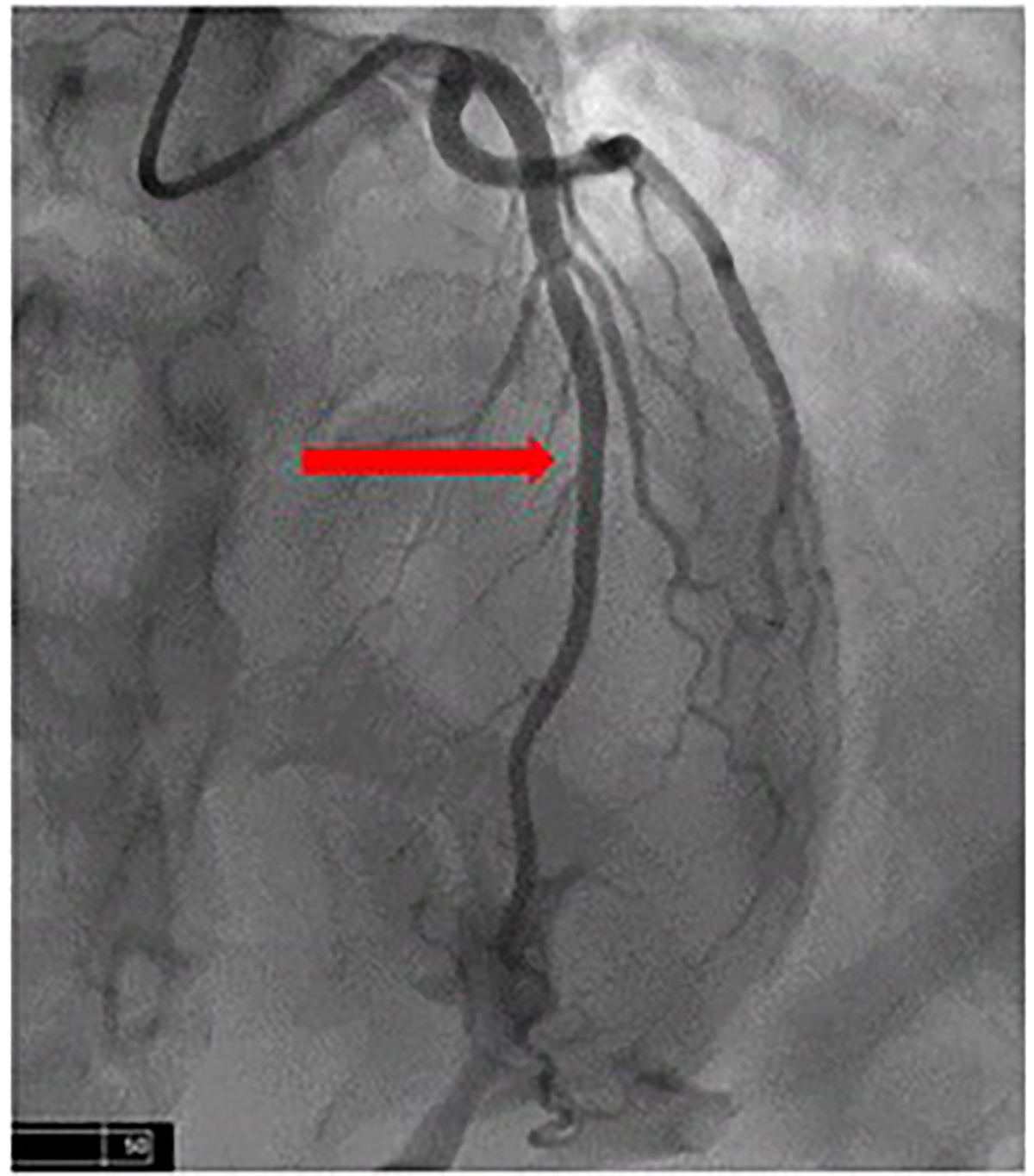

Angiographically, three types of SCAD have been identified (Figure 1).5 Type 1 SCAD is identified by contrast dye staining which reveals double or multiple radiolucent lumens separated by radiolucent flap. Type 2 SCAD is identified by diffuse luminal narrowing or stenosis (usually >20 mm) of the coronary artery without dissection.

Type 2 SCAD is the most common type of SCAD present and has been reported in over 60 percent of SCAD patients. Reliance solely on the traditional angiographic findings of multiple lumens or contrast staining of arterial walls would result in missed diagnosis in more than half of SCAD patients.

Type 3 SCAD is rare and mimics atherosclerosis Ò there is focal or tubular stenosis (<20 mm) but no atherosclerosis in the other coronary arteries. Intracoronary imaging is usually required to confirm Type 3 SCAD.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Patients usually but do not always present with typical symptoms of myocardial infarction. Laboratory and ECG abnormalities include elevated troponin levels and ST-segment abnormalities. Invasive coronary angiography is the "gold standard" used for the diagnosis of SCAD.

Although noninvasive cardiac computed tomography angiography (CTA) can visualize SCAD, it can inadvertently be missed or not well visualized.6,7 IVUS and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are important adjunctive imaging tools during invasive coronary angiography when the diagnosis is uncertain,8 but carry the added risk of iatrogenic dissection and should not be used routinely.

Management of SCAD

Management depends on the patient's clinical presentation, hemodynamic stability, coronary flow and the affected coronary artery. For clinically stable patients with preserved coronary artery flow, conservative medical management is generally recommended. This is based on observations that SCAD vessels tend to heal, and intramural hematomas resolve over time. The time course for healing typically occurs by one month.1,2

Conservative medical therapy with low-dose aspirin for at least one year, beta-blockade (if tolerated) and heart failure guideline-directed medical therapy (if LV systolic dysfunction present) is recommended.

The use of statins should be individualized based on guidelines for primary prevention of CAD. Chronic anticoagulation is not indicated unless there is another medical reason for systemic anticoagulation.

Conservatively managed patients should be monitored as inpatients for at least three days as some patients develop complications necessitating emergency revascularization. For patients with hemodynamic instability, malignant arrhythmias, recurrent angina or left main artery involvement, revascularization should strongly be considered. Revascularization can be performed either with PCI or CABG.

The long-term prognosis for SCAD patients is good, although recurrence can occur.9 It's important to note that coronary artery revascularization does not prevent the recurrence of future SCAD events. Systemic hypertension9 and coronary artery tortuosity10 have been associated with recurrent events.

A multidisciplinary team-based management may be required depending on the patient's clinical presentation, coexistent extracoronary vascular arteriopathies and comorbidities.1

Extracoronary arterial screening is strongly recommended due to the high association of extracoronary vascular arteriopathies such as other isolated dissections, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), aneurysms, tortuosity and dilatation.7 FMD is the most common arteriopathy associated with SCAD.

Screening should be performed with CTA or magnetic resonance angiography (head, neck, abdomen and pelvis). Mental health counseling may be required for patients with emotional distress associated with SCAD. All patients should be referred to cardiac rehabilitation. Although patients are advised to avoid extreme physical exertion including competitive sports, moderate physical activity is encouraged.

Pregnancy is not recommended after an episode of SCAD. If pregnancy is contemplated, maternal-fetal medicine and cardiology should be involved during the pregnancy. Migraine is a common comorbidity in patients with SCAD.

Patients with migraines should avoid vasoconstricting medications and neurology referral may be necessary. Medical genetics referral may be warranted especially if there is a family history of early sudden cardiac death or inheritable connective-tissue disorders.

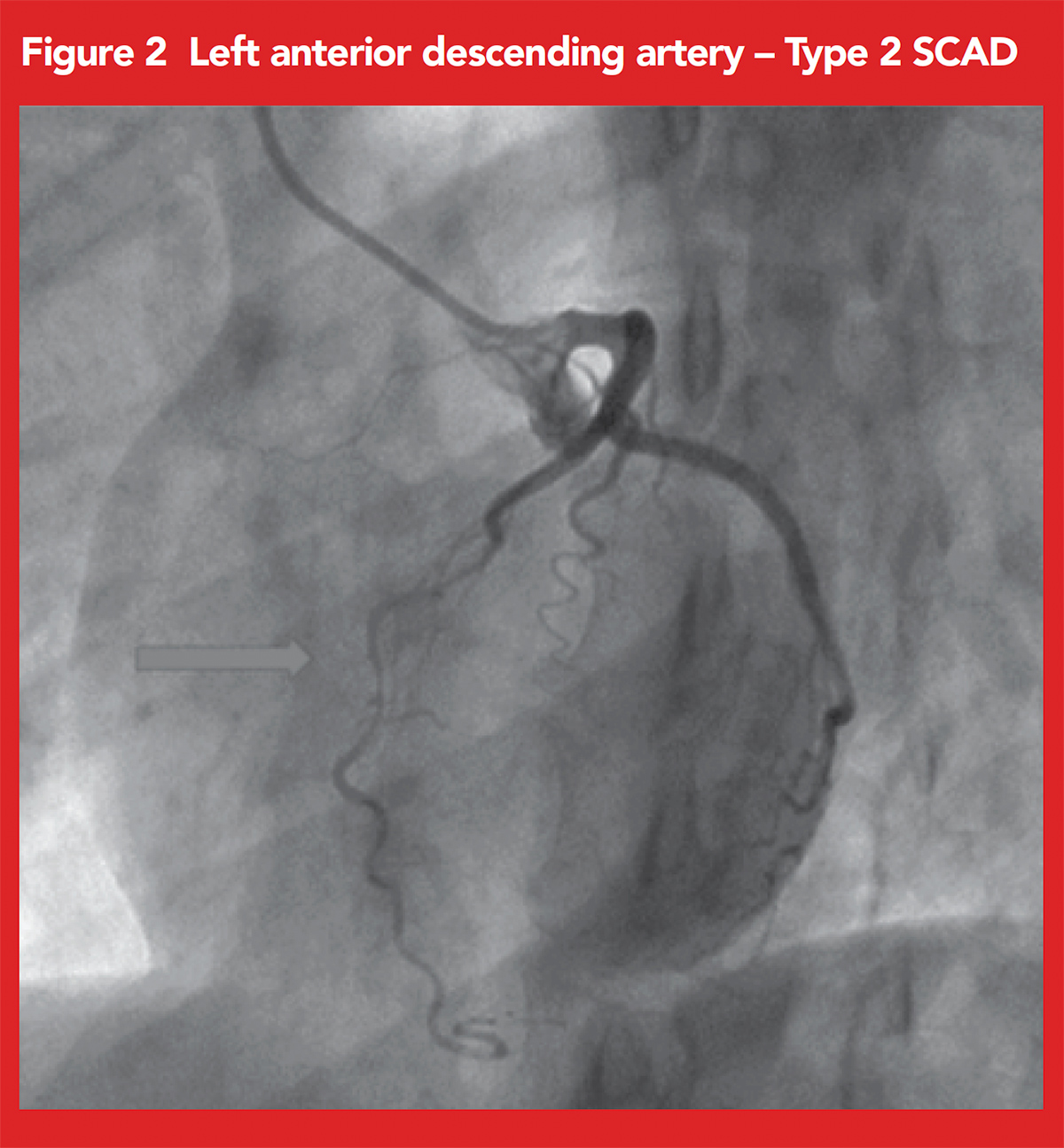

Our patient underwent coronary angiography, which showed significant diffuse narrowing of the mid-LAD concerning for Type 2 SCAD (Figure 2).

Due to the myocardial territory at risk for ischemia, a clinical decision was made to perform PCI, which was performed with overlapping drug-eluting stents. Aspirin and clopidogrel were initiated, without statin therapy.

Her coronary angiogram images were sent to the Mayo Clinic SCAD Registry which confirmed the SCAD diagnosis. Head and neck CTA revealed FMD in the distal left vertebral artery. Chest abdomen and pelvis CTA did not reveal any concerning vascular findings. She was chest pain free at her one-year cardiovascular follow-up.

In conclusion, it's important to consider the female-predominant cardiovascular diseases in women with chest pain. These conditions include Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and SCAD. SCAD should be considered in younger and middle-aged women without traditional risk factors for atherosclerotic CAD who present with symptoms concerning for acute coronary syndrome.

Health care providers and patient/community education on female-predominant cardiovascular diseases is important.11

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Vascular Medicine, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Implantable Devices, Genetic Arrhythmic Conditions, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Interventions, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, CHD and Pediatrics and Quality Improvement, Nonstatins, Novel Agents, Statins, Acute Heart Failure, Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Coronary Artery Disease, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Angiography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Nuclear Imaging, Exercise, Stress, Sports and Exercise and Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Sports and Exercise and Imaging

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Pregnancy, Coronary Artery Disease, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors, Coronary Angiography, Nitroglycerin, Physical Exertion, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Fibromuscular Dysplasia, Cardiac Rehabilitation, Troponin, Magnetic Resonance Angiography, Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy, Aspirin, Tomography, Optical Coherence, Risk Factors, Drug-Eluting Stents, Infarction, Chills, Constriction, Pathologic, Stress, Psychological, Inpatients, Vertebral Artery, Dilatation, Follow-Up Studies, Iatrogenic Disease, Genetics, Medical, Myocardial Infarction, Mental Health, Ticlopidine, Perimenopause, Coronary Vessel Anomalies, Electrocardiography, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Atherosclerosis, Death, Sudden, Cardiac, Chest Pain, Registries, Heart Failure, Hematoma, Prognosis, Primary Prevention, Aneurysm, Postpartum Period, Abdomen, Sports, Fever, Exercise, Comorbidity, Pelvis, Hemodynamics, Connective Tissue Diseases, Migraine Disorders, Referral and Consultation, Health Personnel, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Counseling, Staining and Labeling, Patient Care Team, Connective Tissue, Neurology, Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2

< Back to Listings