Cover Story | The Heart Study Heard Around the World: Origins of Framingham and its Continued Legacy

Credit: NHBLI

Credit: NHBLI

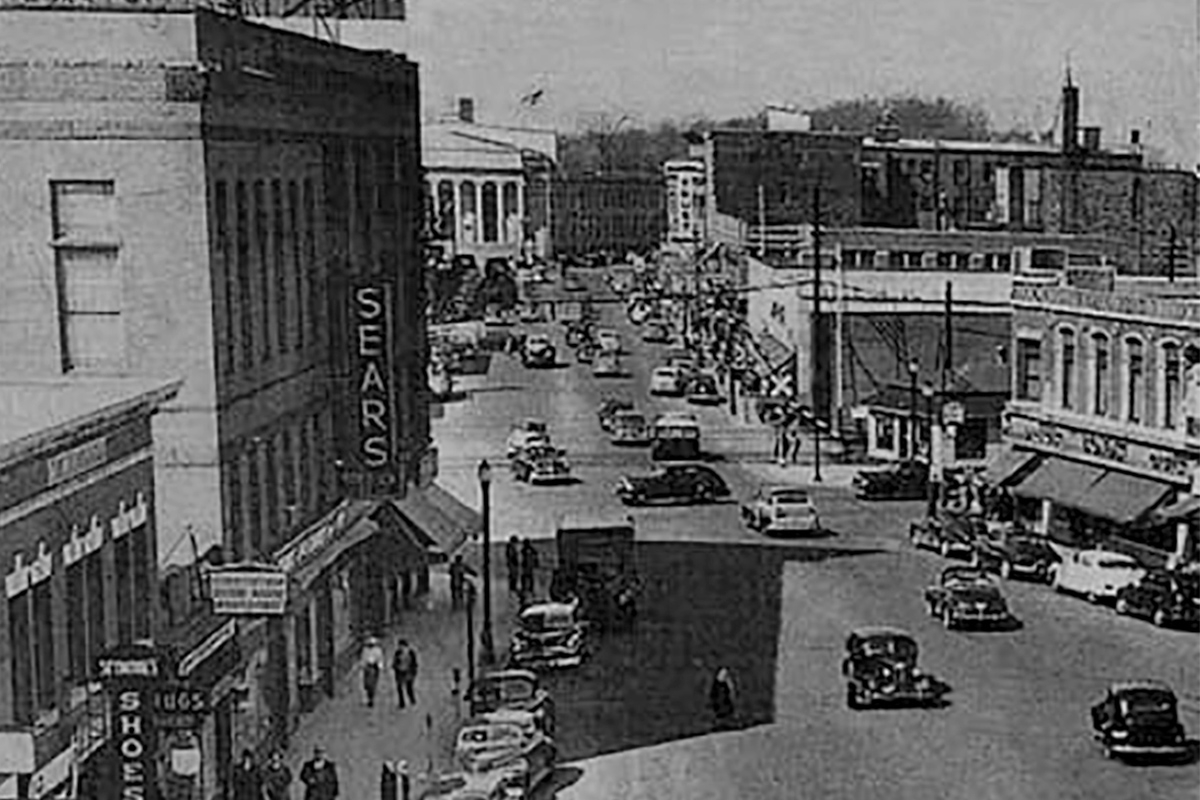

Oct. 11, 2013 marked 65 years since the first citizen volunteer was examined in the Framingham Heart Study.

Today, although every cardiologist recognizes the importance of the Framingham Heart Study in preventive cardiology, most are far less aware of the level of cardiovascular ignorance in that earlier era; the fascinating events that preceded its creation; or the breadth of its impact on world health.

The Origins of the Framingham Heart Study

The World War II era witnessed two events that were to forever alter the practice of cardiovascular medicine. The first was the discovery of penicillin and other antibiotics, which precipitated the fall of infectious disease as the nation’s leading cause of death.

In its place emerged a ferocious new epidemic of cardiovascular disease driven in part by the widespread distribution of free cigarettes to soldiers during the war. By 1948, 44 percent of deaths in the U.S. were due to cardiovascular disease, a 20 percent increase in just eight years.1

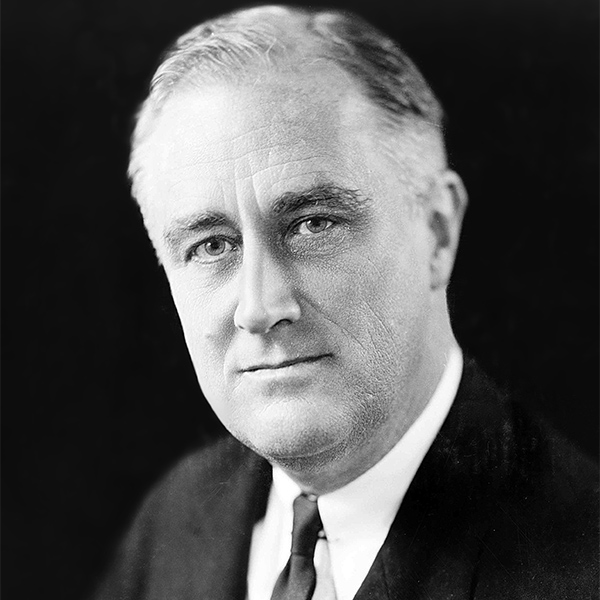

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

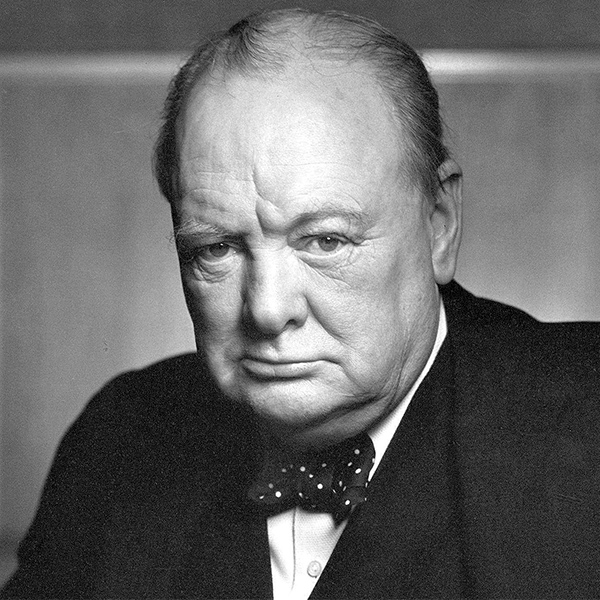

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

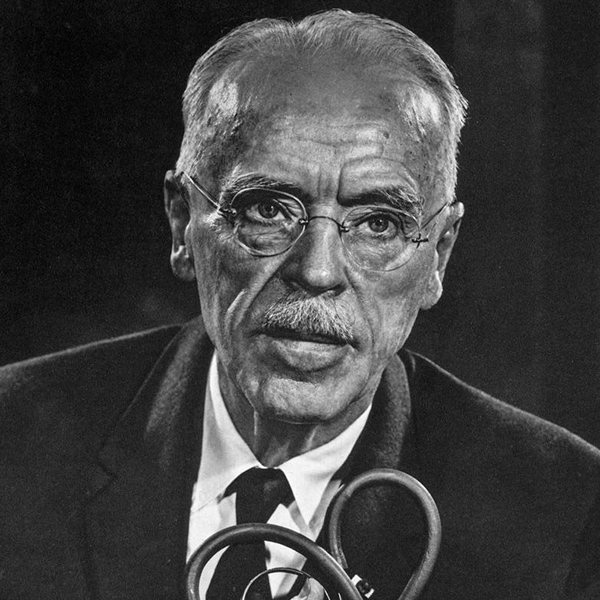

Lord Charles Moran, MD

Lord Charles Moran, MD

The second event was the very public decline of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s health due to cardiovascular disease. When Roosevelt assumed the presidency in 1933 his blood pressure (BP) was reported at 140/100 mmHg, but by the time America entered the war, his BP had climbed to 188/105 mmHg – a change deemed by his physician to be “no more than normal for a man of his age.”2

After all, rising blood pressure was considered to be part of the natural aging process, and an acceptable systolic blood pressure was considered 100 plus the patient’s age. No treatment was considered.

As the war progressed, Roosevelt began to exhibit obvious and dramatic physical deterioration. When Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited the White House in May 1943, he commented to his own physician that the President appeared to be “a very tired man.”3

Less than a year later, Roosevelt was admitted to Bethesda Naval Hospital with dyspnea on exertion, abdominal distension, cyanosis and an X-ray that showed cardiomegaly. With a BP of 186/108, Roosevelt’s cardiologist diagnosed hypertensive heart failure, and prescribed digitalis, salt restriction and phenobarbital.

Months later when Roosevelt met Churchill and Stalin at the historic Yalta Conference, Churchill’s personal physician Lord Charles Moran, MD, wrote in his diary: “The President appears a very sick man… I give him only a few months to live.”4 A few weeks later this prediction came true. Roosevelt, with a BP of 300/190, was pronounced dead of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 63. The heart disease epidemic had hit home.

In 1948, as newspapers trumpeted the cardiovascular disease epidemic, President Harry Truman, who was vice president under Roosevelt, signed the National Heart Act into law establishing the National Heart Institute (NHI). The Act also included a $500,000 grant for a 20-year epidemiologic study of cardiovascular disease, soon to be called the Framingham Heart Study.

Design of the new study fell to a young Public Health Service physician, Gilcin Meadors, MD, who defined the mission: “to study the expression of coronary artery disease (CAD) in a ‘normal’ or unselected population and to determine the factors predisposing to the development of the disease through clinical and laboratory exam and long-term follow-up.”5

Paul Dudley White, MD

Paul Dudley White, MD

Harvard’s famed cardiologist, Paul Dudley White, MD, lobbied for initiation of the study in nearby Framingham, MA, and argued that the town’s 28,000 inhabitants were a perfect representative slice of middle class, multiethnic 1940s America.

White noted that Framingham also had unique appealing assets, including a record of individuals who had participated in a prior epidemiologic study of tuberculosis; only two hospitals (later just one) which would make it easier for long-term follow-up; and easy access to consultants at some of the nation’s most respected medical institutions.

Credit: Framingham Heart Study Archives

Credit: Framingham Heart Study Archives

When Framingham was finally selected, Meadors set up a highly effective community-wide recruitment process, and emphasized neighbor-to-neighbor communication. However, within months of the first patient examination in October 1948, the NHI took control of the study – a move that turned out to be absolutely critical.

The biometrics staff changed the method of recruitment from a potentially biased volunteer solicitation to active recruitment of a random sample of Framingham adults. Unlike contemporary epidemiologic studies, half the participants were women.

At the urge of local physicians, the investigators agreed to offer no potentially study-contaminating medical advice to participants, and instead forwarded information to the subject’s personal physician.

Thomas Dawber, MD

Thomas Dawber, MD

William Kannel, MD, MPH, FACC

William Kannel, MD, MPH, FACC

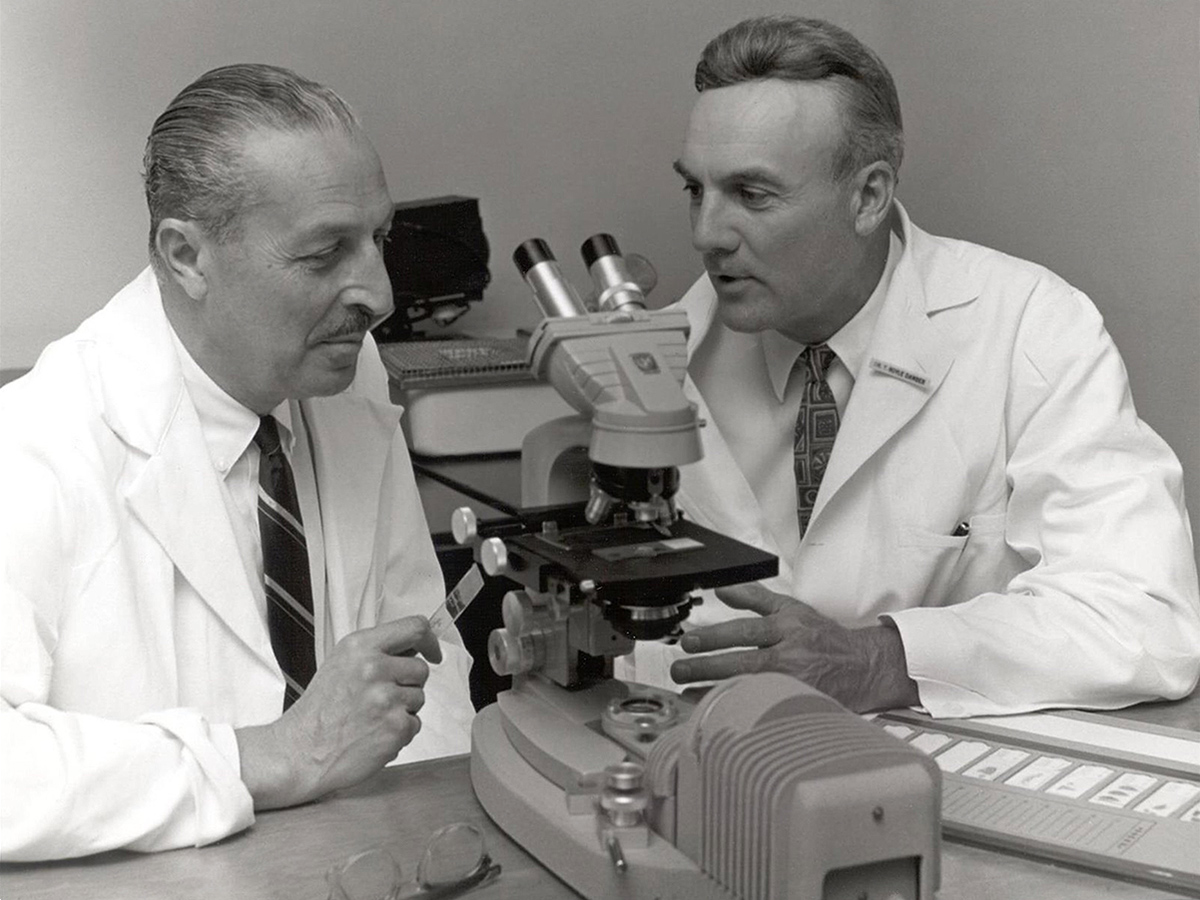

Over the ensuing four years, Framingham Heart Study Director Thomas Dawber, MD, supervised the recruitment of 5,209 citizens aged 28-62. Biennial follow-up also began.

A stunning now-forgotten fact about the Framingham Heart Study is that at the end of its 20-year grant, NHI announced its intent to phase out the study in the ensuing year.

The Framingham Heart Study investigators, led by its former and current directors Dawber and William Kannel, MD, MPH, FACC, scoured the country for private funds, and raised money from seemingly unlikely contributors like the Tobacco Research Council and Oscar Mayer meat processing.

The turning point, however, was a classic example of Washington, DC, decision-making. White had a private discussion with his patient, President Richard Nixon, who convinced the NHI to reverse its position and continue the study. The newly extended Framingham Heart Study next recruited children of the original volunteers, a visionary masterstroke for genetic studies decades later.

Framingham Heart Study Today

Hypertension

Nine years after the entry of the first participant, the Framingham Heart Study began to publish groundbreaking results. In a fitting homage to the untimely death of President Roosevelt, the first major publications dealt with hypertension.

Sir James Black, FRCP, FRS, FACC

Sir James Black, FRCP, FRS, FACC

Consistent with the thinking of the time, after arbitrarily defining hypertension as ≥ 160/95 mmHg, the Framingham Heart Study reported that hypertension conferred a four-fold greater risk of developing new CAD, and soon thereafter confirmed an increase in the risk of stroke as well.6

These reports stimulated the search for more effective antihypertensive agents, including the development of propranolol by Nobel Laureate Sir James Black, FRCP, FRS, FACC, in the early 1960s. Today’s World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension risk prediction charts trace their origin to these early Framingham Heart Study studies.

Heart Failure

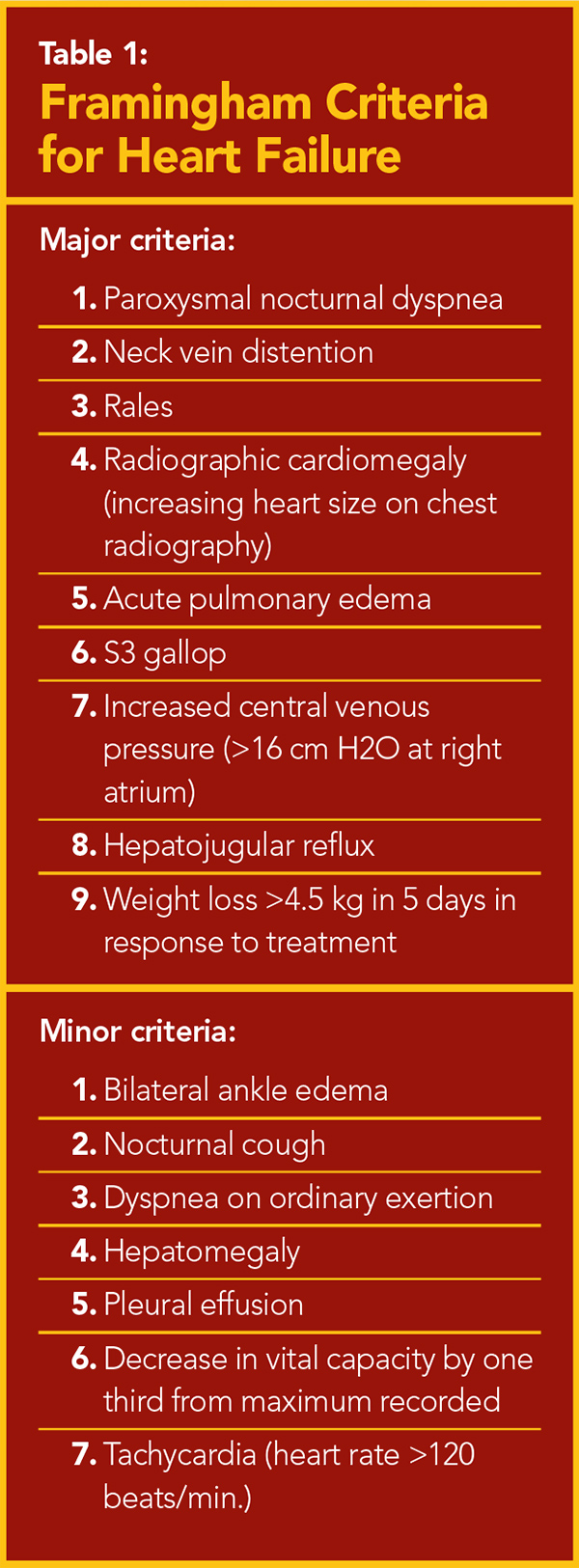

At the time of Roosevelt’s death, cardiology had no standard criteria for heart failure. As a result, clinical trials used each investigative group’s own arbitrary definition. In 1971, when their records identified a rising incidence of heart failure among its volunteers, the Framingham Heart Study created a panel of criteria that they tested retrospectively against 20 years of collected data.

From this analysis, nine major criteria and seven minor criteria emerged (Table 1). Heart failure was defined as the presence of at least two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria. The investigators reported that hypertension preceded 75 percent of heart failure presentations whereas CAD preceded it in less than 40 percent. Myocardial infarction was associated with a six-fold increase in the risk of heart failure.7

In the years that followed these original studies, the Framingham Heart Study analyzed the long-term survival of heart failure patients. At the time of the first report in 1971, 60 percent of men were dead within five years of diagnosis and 80 percent had died within 10 years.

In the 1990s with the introduction of new pharmacotherapies, the Framingham Heart Study reported that five year mortality had fallen modestly with the introduction of new pharmacotherapies.8

The Framingham data also revealed that clinical manifestations of heart failure often existed in the absence of disordered systolic function well before echocardiography was employed to clearly establish the diagnosis of diastolic heart failure.

The Framingham Heart Study reported a gradation in long term prognosis between those without clinical heart failure, diastolic failure and systolic failure. Framingham Heart Study heart failure criteria, still in modern use, have been employed in innumerable clinical trials worldwide.

Stroke and Atrial Fibrillation

In 1965, Dawber, Kannel and their co-investigators described risk factors for stroke based on the Framingham Heart Study. Their results established the relationship between systolic hypertension and stroke, and that hypertension constituted a greater risk factor than CAD.

In addition, a 1978 landmark Framingham Heart Study showed that non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation conferred a five-fold increase in the risk of stroke.9 They urged the creation of trials of both antiarrhythmic and anticoagulant therapy. The subsequent trials became the basis for modern management guidelines.

Coronary Artery Disease

The concept “risk factors for CAD” was championed by Dawber and Kannel’s 1961 Annals of Internal Medicine publication entitled “Factors of Risk in the Development of Coronary Heart Disease,” which presented a six-year follow up of the Framingham population.

These early data provided the logical basis for creation of a method for multivariable prediction of future risk of a coronary event in an individual patient. In 1967, the Framingham investigators described a multivariable logistic model with seven risk factors: age, systolic blood pressure, number of cigarettes smoked, total cholesterol, ECG abnormalities, weight and hemoglobin. Men and women in the highest decile had a 30-fold and 70-fold greater risk than those in the lowest decile.10

Credit: NHBLI

Credit: NHBLI

As Framingham Heart Study data accumulated over time, the individual risk components evolved. Diabetes was found to confer a three-fold increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. When measurements of cholesterol sub-fractions became available, the Framingham Heart Study documented the importance of the high LDL-C and low HDL-C.11

The multiple new observations culminated in the 1998 publication of the Framingham Risk Score for CAD. The new calculator, which established the three categories of based on 10-year risk, was adopted by the Adult Treatment Panel of the National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines.

The Framingham Risk Score became the accepted worldwide foundation for decision-making in preventive management of individuals at risk of developing future CAD.

The Global Impact of the Framingham Heart Study

In 2010, Kannel, now retired, was interviewed about his perception of the impact of Framingham Heart Study. His response is memorable: “I think Framingham has served as a model for many other longitudinal cohort studies and was the first that included women. I think the study created a worldwide transformation of preventative medicine and changed the way in which the medical profession and the general population perceived the genesis of disease.”12

References

- Oppenheimer GM. Becoming the Framingham Study 1947–1950. Am J Public Health. 2005; 95: 602–610.

- Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet. 2014 Mar 15;383(9921):999-1008.

- Bruenn HG. Clinical Notes on the Illness and Death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Ann Intern Med. 1970; 72: 579-591.

- Lomazow S Fettmann E. FDR’s Deadly Secret. Public Affairs. January 2010.

- Etheridge EW. Sentinel for Health: A History of the Centers for Disease Control. Berkeley, CA. University of California Press; 1992.

- Dawber TR, Moore FE, Mann GV. Coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1957; 47: 4–24.

- Kannel WB, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, McKee PA, Feinleib M. Role of blood pressure in the development of congestive heart failure. The Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1972; 287: 781–87.

- Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D. The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993; 22: 6A-13A.

- Wolf PA, Dawber TR, Thomas HE Jr, Kannel WB. Epidemiologic assessment of chronic atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke: the Framingham study. Neurology. 1978; 28: 973–77.

- Truett J, Cornfield J, Kannel W. A multivariate analysis of the risk of coronary heart disease in Framingham. J of Chronic Disease. 1967; 20: 511-524.

- Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham study. Am J Med. 1977; 62: 707–14.

- Wilson P, Greenberg H. Interview of William Kannel, M.D. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2010; 53: 4–9.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Dyslipidemia, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Statins, Acute Heart Failure, Echocardiography/Ultrasound, Hypertension

Keywords: Follow-Up Studies, Pleural Effusion, Global Health, X-Rays, Edema, Electrocardiography, Cholesterol, Hemoglobins, Tobacco, United States Public Health Service, Central Venous Pressure, Cough, Hypertension, Vital Capacity, Echocardiography, Cyanosis, Pulmonary Edema, Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, Tuberculosis, Weight Loss, Propranolol, Digitalis Glycosides, Phenobarbital, Heart Rate, Dyspnea, Tachycardia, Cardiomegaly, Financial Management, Prognosis, Heart Failure, Respiratory Sounds, Hepatomegaly, Logistic Models, Diabetes Mellitus, Cerebral Hemorrhage, Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications

< Back to Listings