Focus on EP | The Value of Mapping: A Primer For Clinicians

"So, what did the map show?" When walking by the electrophysiology lab, you may have overheard this common question exchanged between cardiac electrophysiologists (EPs) to describe an interesting procedural case. For many, the intricacies of what occurs inside the EP lab, particularly for ablation procedures, remain a black box and the language used to describe the process can be equally confusing. The goal of this article is to demystify the concept of mapping, so all cardiovascular clinicians can better understand the procedural care that is being provided by their EP colleagues.

What is Mapping?

Mapping is the term used to describe the process of creating a 3D model of a cardiac chamber to guide the delivery of ablation therapy. The initial model is anatomical, outlining the endocardial surface of the cardiac chamber, and overlaid on this anatomical model are additional data points describing the electrical conduction characteristics of the myocardial tissue at a particular location in the cardiac chamber, including the voltage, velocity and direction of the electrical signal passing through the tissue.

The process of creating a map containing electrical and anatomical properties of a cardiac chamber is termed electroanatomical mapping (EAM). Additional areas of interest, such as the location of the sinus node, atrioventricular (AV) node or regions of abnormal conduction, can be tagged onto the EAM.

The EAM is specific to the cardiac rhythm and if the rhythm changes (from sinus, to paced, to arrhythmia), the electrical properties of the cardiac chamber can change as well. As such, different EAM can be created for different rhythms to uncover additional areas of interest. Furthermore, the EAM for every patient is different, as cardiac anatomy can be altered through normal variation (i.e., number of pulmonary veins), pathology (i.e., dilatation of cardiac chambers), and prior invasive intervention (i.e., scar created by cardiac surgery).

How is Mapping Performed?

EAM is performed by advancing the tip of a mapping catheter into the cardiac chamber of interest and towards the area where mapping data are to be acquired. Each site of contact between the catheter tip and the endocardium is called a point. The location and electrical characteristics of this point are displayed as a graphic, and this graphic is updated continuously as more points are taken.

Different colors on the graphic correspond to varying degrees of a measured electrical parameter (i.e., voltage, velocity, timing of activation, etc.), in a color sequence that mirrors the traditional colors of the rainbow (from red to violet).

Historically, the tip of the mapping catheter was only several millimeters in diameter and the catheter tip would need to make contact with all of the endocardial boundary points for a full complete EAM to be obtained, a process that could take more than an hour. Nowadays, mapping catheter tips have large surface areas so that numerous points can be taken at once, and a complete EAM can be performed within a matter of minutes.

Mapping is akin to playing the game "Marco Polo" in the pool, where a person closes their eyes and tries to understand the outline of the pool and motion of water waves while chasing down a target. This blinded person is aided in the chase by using fingertip contact (the mapping catheter) to understand the physical boundaries of the pool (the anatomy) as well as the pattern of water movement (the conduction).

From Mapping to Ablation

Ultimately, the purpose of EAM is to identify a suitable area for ablation. The amount of mapping that is required to achieve this is dependent on the type of ablation being performed. For pulmonary vein isolation in atrial fibrillation ablation, the EAM needs to define the number and contour of the pulmonary veins in the left atrium.

For premature ventricular complex (PVC) ablation, the EAM needs to localize the site of PVC origin which may require mapping of both the right and left ventricle. For atrial flutter, the EAM should ideally confirm and define the entire reentrant circuit via a specialized mapping approach called activation mapping. The more descriptive and accurate the EAM, the more precise the ablation target. Ideally, only pathologic cardiac tissue is ablated as indiscriminate ablation of normal tissue can have consequences, particularly injury to the native conduction system (sinoatrial node, AV node, Purkinje system, etc.).

Mapping For VT Ablation

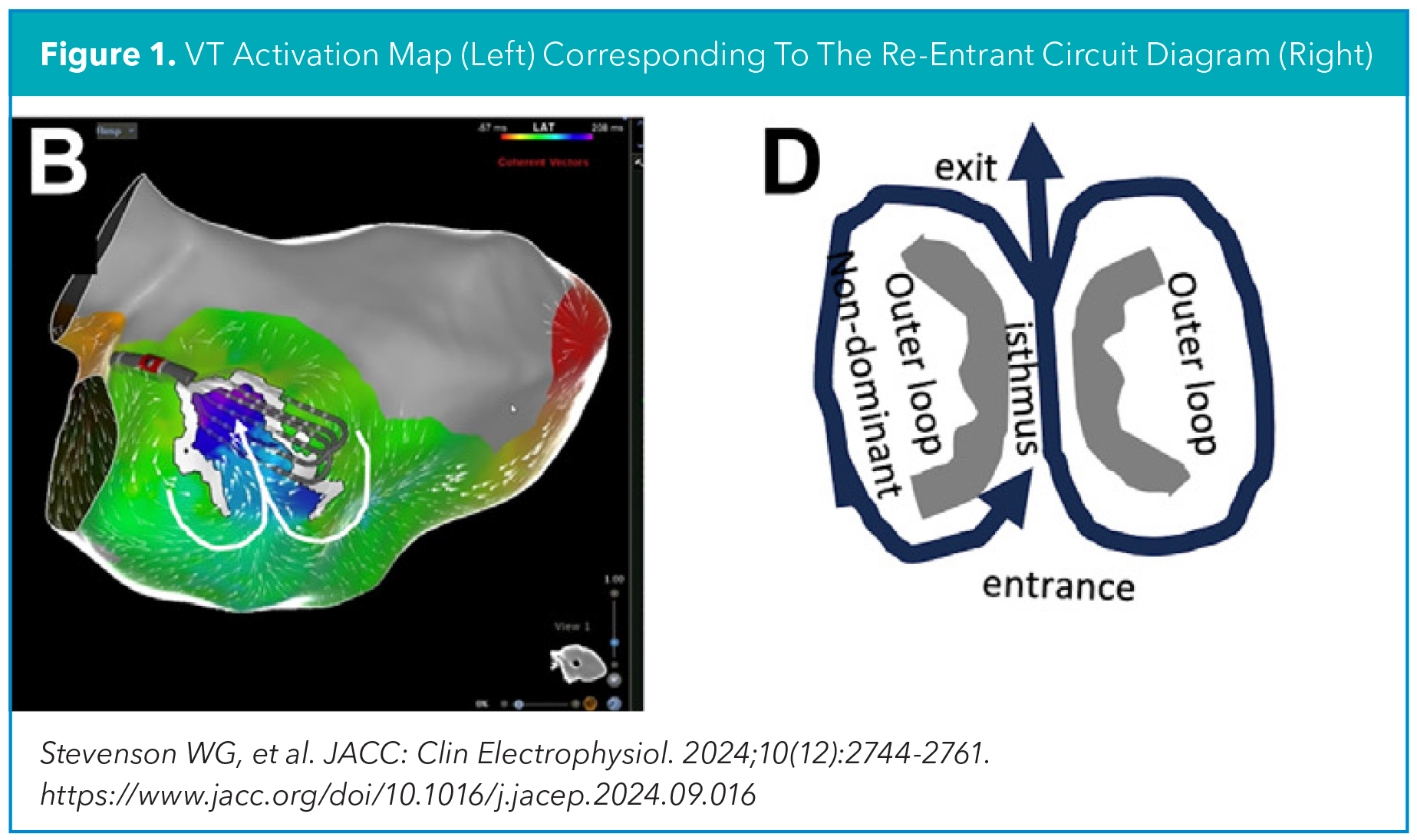

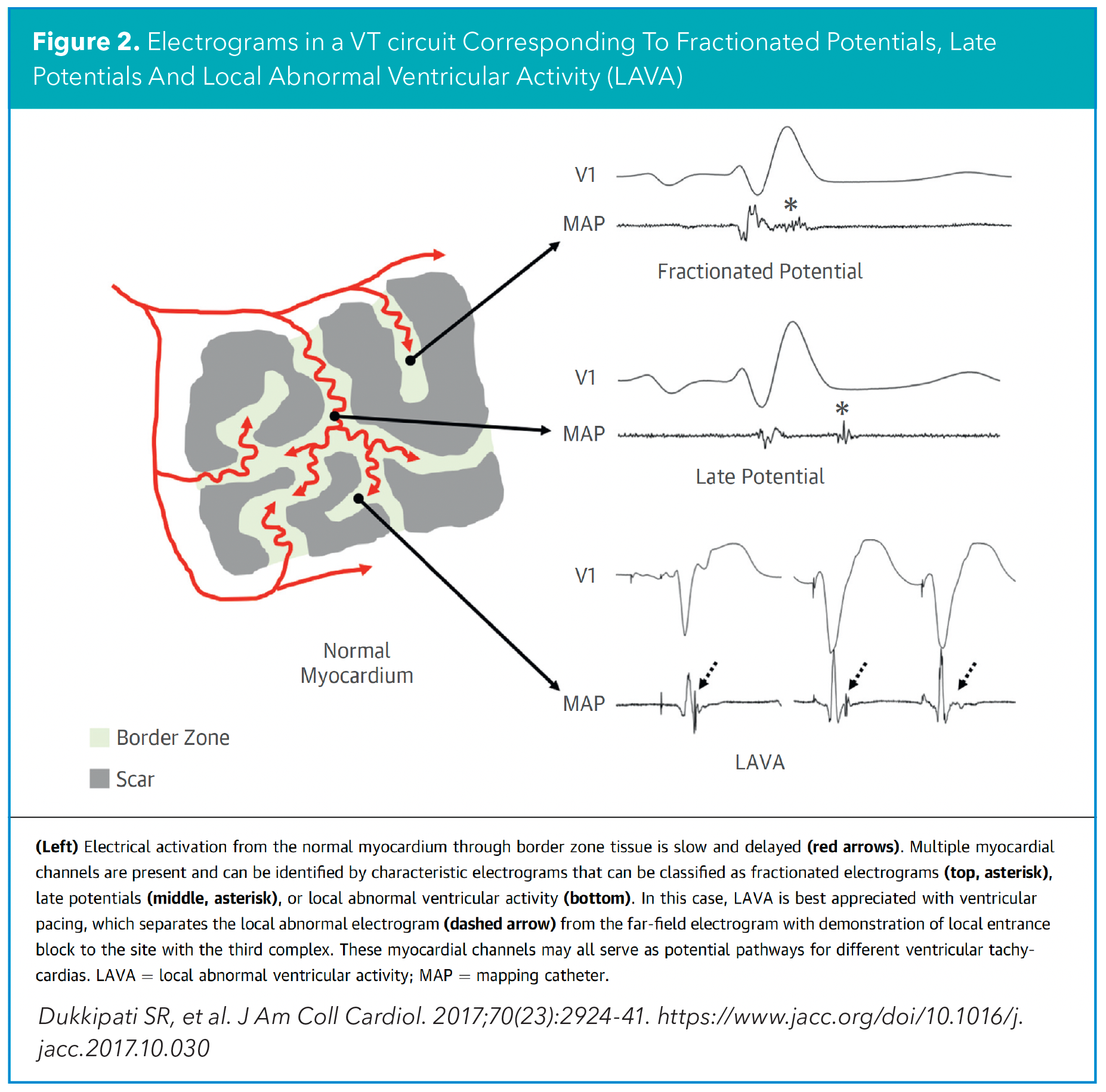

In patients with ischemic heart disease who undergo VT ablation, EAM is needed to pinpoint the focal area(s) hidden in the ventricular scar whose elimination would prevent further VT. The gold standard approach for EAM is activation mapping, which is performed during VT to delineate the course of the reentrant VT circuit, such as the entrance and exit, and most importantly localize the isthmus, a narrow channel within this circuit, that serves as the most effective site for ablation. Activation mapping can be challenging to perform as VT is often poorly tolerated from a hemodynamic perspective. As such, novel ways of identifying the isthmus during sinus rhythm or paced rhythm have been explored, through either a substrate mapping and/or functional mapping approach (Figure 1).1

Substrate mapping aims to identify the VT critical isthmus by detecting "static" electrical signals of the diseased myocardial tissue involved in the VT critical isthmus. This includes reduced voltages (bipolar voltage <1.5mV), late electrical potentials (electrograms that occur after the end of the QRS), fractionated potentials (multicomponent deflections within the local QRS electrogram) and other types of local abnormal ventricular activity (LAVA) (Figure 2).

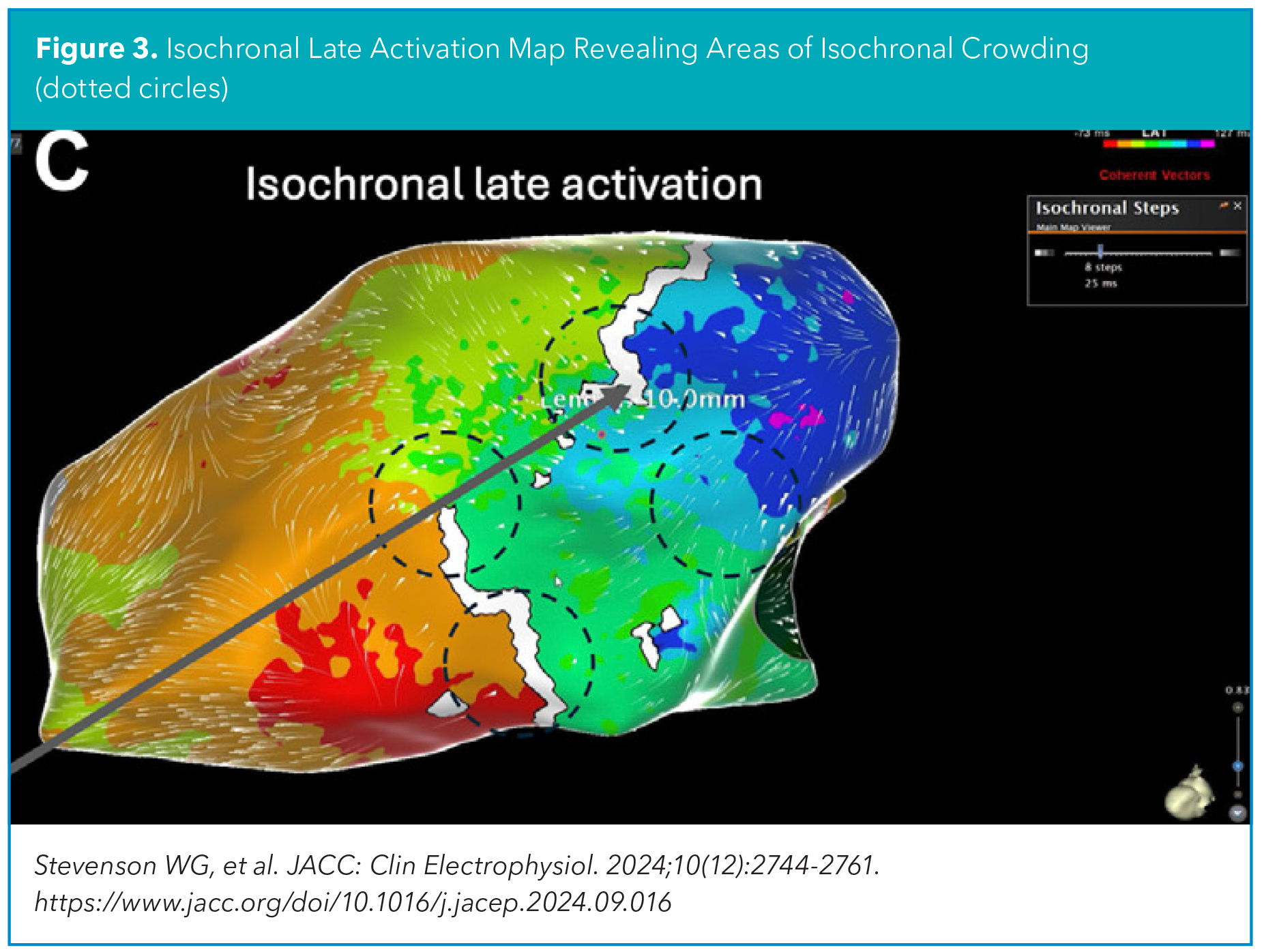

Functional mapping aims to identify the VT critical isthmus by detecting "dynamic" electrical properties of the diseased myocardial tissue involved in the VT critical isthmus. This includes reduced conduction velocity resulting in isochronal crowding (isochronal late activation mapping, ILAM), decremental conduction behavior to paced extrastimuli (deep evoked delayed potentials, DEEP mapping), and paced QRS morphology resembling the clinical VT (pace mapping) (Figure 3).

I encourage all clinicians to become more actively engaged in the care of their patients who go to the EP lab. Similar with how coronary angiograms can be understood by non-interventional cardiologists, EAM can also be understood by non-EPs. Instead of jumping ahead to just read the conclusion of an ablation report to determine if the outcome was successful, the description of the EAM can be reviewed to understand why the procedure was successful (or not). The next time you walk by the EP lab when your patient is undergoing ablation, feel free to ask: "So, what did the map show?"

This article was authored by Edward Chu, MD, FACC (@Ed_Chu_MD), an electrophysiology attending physician in Miami, FL.

Reference

- Stevenson, W, Richardson, T, Kanagasundram, A. et al. State of the Art: Mapping Strategies to Guide Ablation in Ischemic Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2024;10(12):2744-2761.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Pulmonary Veins, Models, Anatomic, Electrophysiology