Integrating Care Solutions For the Patient Receiving Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

What is Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy?

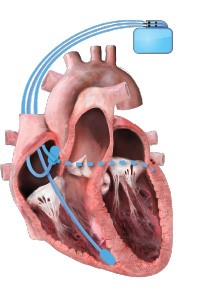

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is a pacing therapy for patients with heart failure (HF), which is prescribed to improve symptoms, promote favorable ventricular remodeling, and reduce the risk of HF hospitalization. CRT is unique among cardiovascular therapeutics in that it also improves mortality in select patients, particularly those whose HF is driven by dyssynchrony from conduction delays that manifest as wide QRS interval, especially in the setting of a left bundle branch block (LBBB). CRT is traditionally delivered via a three-lead pacing system to perform biventricular pacing (BVP), with wires placed into the right atrium, right ventricle, and a branch of the coronary sinus, with the goal of achieving >99% pacing.1

Indications for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

The society guidelines for CRT can be reviewed for nuances regarding the indications for CRT. Still, a broad overview of the indications is listed below for the purposes of this article.2,3

- CRT is indicated in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) who have been optimized on guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) (i.e., doses have been titrated to either target doses or maximally tolerated doses of GDMT as per clinical guidelines) and have a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%, remain symptomatic (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class II-IV symptoms), and are in sinus rhythm with a QRS >150 msec in an LBBB pattern.

- CRT should be considered in symptomatic patients with HFrEF who have been optimized on GDMT, have an LVEF ≤35%, and are in sinus rhythm with a QRS of 130-149 msec in an LBBB pattern.

- CRT should be considered in symptomatic patients with HFrEF who have been optimized on GDMT, have an LVEF ≤35%, and are in sinus rhythm with a QRS ≥150 msec and non-LBBB pattern.

- CRT should be considered in patients with HFrEF and an LVEF ≤35% in NYHA class III or IV if they are in atrial fibrillation and have an intrinsic QRS ≥130 msec. A strategy for BVP is needed, and this may require atrioventricular nodal ablation if pacing is incomplete (<90-95%).

Management of Nonresponse to CRT

A patient who is not responding to CRT is defined as an individual who experiences disease progression from HF despite the attempted application of BVP.4 A myriad of etiologies should be investigated to address nonresponse.5 These may potentially include but are not limited to the following:

- Patient selection (non-LBBB pattern, QRS not very wide, etc.).

- Lack of 99% manifest BVP (check pacing thresholds).

- Competing atrial or ventricular rhythms reducing BVP proportion.

- Inadequate atrioventricular or ventricular-ventricular intervals.

- Poor lead positioning (i.e., left ventricular lead is apically paced or near a large scar).

Novel Methods to Better Optimize CRT

Concerns about patient nonresponse to CRT have spurred an investigation into new approaches to deliver CRT, including using CRT via conduction system pacing, which may be achieved with His bundle pacing or left bundle branch area pacing, using new device-based algorithms to improve fusion of pacing with intrinsic conduction, and leveraging data from device-based sensors as part of remote monitoring.6 These and other efforts require the integration and collaboration of multiple care clinicians, including HF cardiologists, electrophysiologists, and advanced practitioners, to work in concert to titrate GDMT and adjust device parameters to improve CRT and maximize response.7

Patient Care Disparities in CRT Application

As with every area in medicine, disparities exist regarding CRT. A study from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry showed that Black and Hispanic patients with an indication for CRT are less likely to receive CRT than their White counterparts.8 Black patients have a higher burden of HF; they present earlier and sicker and have a higher rate of hospitalizations for HF. Even with adjustments for HF hospitalizations, fewer Black patients receive CRT.9 Even though women have been shown to derive more benefits from CRT, they are less likely to receive CRT.10 CRT use is low in older adults as well as in Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.11,12

Mechanisms for disparities are complex and beyond the scope of this article, but it is acknowledged that disparities are rooted in structural racism and clinician biases. Reducing and ideally eliminating these disparities must get at the root of their existence. Improving access in underserved areas, addressing clinician biases, creating protocols for procedures and electronic medical record alerts for when CRT or remote monitoring may be indicated, forming multidisciplinary teams to address modifiable risk factors, and implementing policies to improve reimbursement for CRT for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries are strategies to consider.13

Integrating Care Solutions by Bringing Disciplines Together with the Patient

Patients are asked to trust clinicians with implanting a device that comes with very real risks, economic burden, and sometimes less-than-ideal benefits. This means it is incumbent on care team clinicians to work together to assess response to CRT therapy, augmenting the impact with appropriate GDMT while also responding to remote monitoring alerts, including those related to arrhythmias and HF disease progression.14 Clinical workflows must reflect appropriate stakeholder accountability identifying the responsible clinician who should address alerts related to multivariable risk prediction models incorporating variables including, but not limited to, arrhythmia burden, sleep incline, activity, heart rate variability, and intrathoracic impedance to determine if a patient should have therapies addressed and potentially revised.15 Finally, innovation must continue into the realm of patients becoming more empowered owners of their own data related to HF disease progression and/or response to therapies. CRT is an excellent treatment modality when used appropriately and to its utmost capacity.

Educational grant support provided by: Medtronic

To visit the course page for the Integrated Care Solutions for the Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) Patient project, click here!

References

- Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2019;140:e382-e482.

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:e6-75.

- Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3427-520.

- Varma N, Boehmer J, Bhargava K, et al. Evaluation, management, and outcomes of patients poorly responsive to cardiac resynchronization device therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2588-603.

- Curtis AB, Poole JE. The right response to nonresponse to cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2604-6.

- Scheetz SD, Upadhyay GA. Physiologic pacing targeting the His bundle and left bundle branch: a review of the literature. Curr Cardiol Rep 2022;24:959-78.

- Altman RK, Parks KA, Schlett CL, et al. Multidisciplinary care of patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2181-8.

- Farmer SA, Kirkpatrick JN, Heidenreich PA, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Groeneveld PW. Ethnic and racial disparities in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm 2009;6:325-31.

- Sridhar AR, Yarlagadda V, Parasa S, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: US trends and disparities in utilization and outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016;9:e003108.

- Dewidar O, Dawit H, Barbeau V, Birnie D, Welch V, Wells GA. Sex differences in implantation and outcomes of cardiac resynchronization therapy in real-world settings: a systematic review of cohort studies. CJC Open 2022;4:75-84.

- Heidenreich PA, Tsai V, Bao H, et al. Does age influence cardiac resynchronization therapy use and outcome? JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:497-504.

- Marzec LN, Peterson PN, Bao H, et al. Use of cardiac resynchronization therapy among eligible patients receiving an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Registry. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:561-5.

- Mastoris I, DeFilippis EM, Martyn T, Morris AA, Van Spall HGC, Sauer AJ. Remote patient monitoring for patients with heart failure: sex-and race-based disparities and opportunities. Card Fail Rev 2023;9:e02.

- Health Quality Ontario. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, cardiac resynchronization therapy and permanent pacemakers: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2018;18:1-199.

- Mastoris I, Spall H, Sheldon SH, et al. Emerging implantable-device technology for patients at the intersection of electrophysiology and heart failure interdisciplinary care. J Card Fail 2022;28:991-1015.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Implantable Devices, EP Basic Science, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy, Heart Failure, Stroke Volume, Bundle-Branch Block, Ventricular Function, Left, Cicatrix, Electric Impedance, Maximum Tolerated Dose, Bundle of His, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Hospitalization, Disease Progression, Patient Care Team, Registries

< Back to Listings