Cover Story | Global is Local: Rheumatic Heart Disease Around the World (Including Your Clinic)

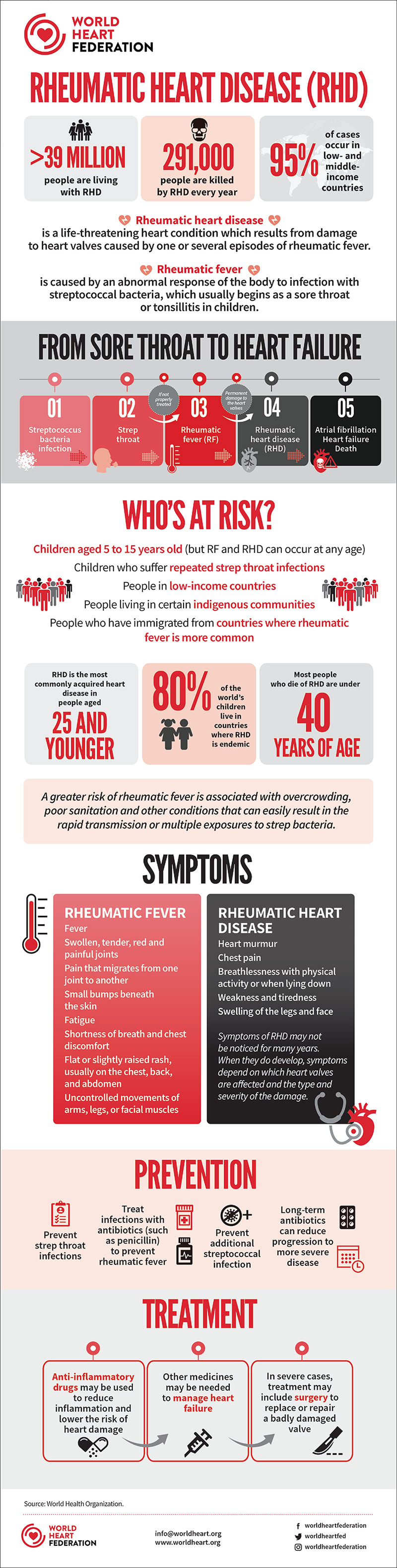

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is a preventable disease that affects 40.5 million people around the world and was responsible for more than 305,000 deaths in 2019.1 It is a sequela of rheumatic fever, which occurs subsequent to one or more bouts of infection with group A streptococci (GAS).

The bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes is ubiquitous and passes easily from person to person, most commonly affecting those between the ages of four and 15. Women are about 1.8-times more likely to be impacted than men, for a variety of reasons that include inherent genetic differences and greater exposure to GAS through child rearing.2

In some cases, repeated strep infections can lead to rheumatic fever, an autoimmune reaction that can cause inflammation and scarring of the heart valves. The attack rate, defined as the percentage of patients with untreated GAS pharyngitis who develop acute rheumatic fever, is relatively low (<6% in individuals living in GAS-endemic regions) but as many as one-third of patients who develop rheumatic fever do so after asymptomatic GAS infection.3 RHD is the most commonly acquired heart disease in people under the age of 25.

Not Gone, But Forgotten

RHD is a disease of deprivation in that it occurs almost exclusively in individuals who lack reliable primary health care. Socioeconomic conditions leading to increased GAS exposure include household crowding, poor hygiene and poor access to medical care.3 It is often referred to as a disease of poverty and, indeed, the majority of cases are found in low-income countries.

But while RHD, and its antecedent rheumatic fever, has largely disappeared from wealthy countries, it is far from unheard of. Nor is it only immigrant cases that present to North American clinics.

"In the U.S., RHD is rare. Sometimes we see immigrants who present with RHD. But for anyone living in the U.S. or elsewhere in a setting where primary health care is poor or not readily accessed and where there's any kind of crowding and lack of sanitation – which could just be school – there is the potential for untreated strep throat and rheumatic fever," says Jeremiah Mwangi, MA, director of Policy and Advocacy at the World Heart Federation (WHF).

A Vaccine For GAS?

"The person who develops a vaccine that targets group A strep could win a Nobel prize," says Taubert. "Even if only 20% or 30% of sore throats are caused by strep, worldwide that is a really large number of kids."

An effective vaccine will prevent not only strep throat and impetigo but also more serious invasive disease (e.g., necrotizing fasciitis) and post-infectious complications like rheumatic fever.

It's estimated that 288.6 million episodes of strep A sore throat occur among children (five to 14 years) each year globally and that one in three children experience one or more episodes of sore throat over a 12-month period. Infection with Strep A causes 500,000 annual deaths, of which invasive Strep A infection, including sepsis, and skin and soft tissue infections, has an estimated annual mortality of 150,000.

The economic incentive is certainly there too. The total cost of GAS pharyngitis just in school-aged children in the U.S. is estimated at between $224 to $539 million per year, almost half of which is nonmedical.7 And that's just strep throat and just in the U.S.

"It would have an enormous impact," says Mwangi, "which is why there's so much interest, but depending on who you talk to in the community, it's still 10 to 15 years away," he notes.

Two recent studies amplify this point. A 2021 study led by pediatric cardiologists Sarah R. de Loizaga, MD, and Andrea Beaton, MD, the latter a leading figure in RHD research, showed that the majority of recent cases in the U.S. of acute rheumatic fever and RHD are homegrown, rather than the result of foreign exposure.4

In a 10-year review of 22 U.S. pediatric medical centers, data for 947 cases showed a median age at diagnosis of nine years. Of note, 89% of patients had health insurance and 82% were first diagnosed in the U.S. Only 13% reported travel to an endemic region before diagnosis, wrote de Loizaga and Beaton, both from the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

In a 2022 retrospective cohort study that used Society of Thoracic Surgeons data, Hawkins, et al., found that of 6,625 mitral valve procedures, 835 (12.6%) were due to rheumatic disease.5 This proportion increased by 0.39% per year from 2011 to 2019, with high variability among hospitals. Rheumatic patients were younger (62 vs. 65 years; p<0.0001), more often female (75% vs. 43%; p<0.001) and had a greater burden of heart failure, multivalve disease and lung disease, but less coronary artery disease.

Hawkins, et al., found that RHD patients required more frequent transfusions and longer hospital stays with more intensive care days. The presence of RHD was not associated with greater operative mortality or major morbidity.

"Anywhere kids congregate there tends to be strep. There are many reasons that strep throat is not diagnosed and the child (and typically it is a child) doesn't get an antibiotic. This can happen in wealthy countries like the U.S. as well as in low- and middle-income countries," says Kathryn Taubert, PhD, FACC.

Taubert, a cardiovascular pathophysiologist and adjunct professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center, lectures on rheumatic fever and heart disease globally and has served as vice president of International Science and Health Strategies at the American Heart Association and chief science officer at the WHF.

"For some 70% or 80% of kids who get a sore throat, it's viral, so an antibiotic is not given. In the developing world, for sure, but even in places like rural America, where the nearest doctor is 15 miles away and there's no transportation, there are many reasons that strep throat goes undiagnosed and untreated. And keep in mind that some cases are asymptomatic," she says in an interview with Cardiology.

"The treatment is simple, but the barriers and the sheer incidence and prevalence of strep throat make things more complicated," Taubert adds.

Global and Local Efforts in RHD Prevention

As the march of RHD continues in poorer countries and among vulnerable groups in rich ones, there is renewed interest in expanding the evidence base and finding new approaches to tackle its many facets.

ACC is partnering with the WHF for ACC.23/WCC in March in New Orleans, where global health topics like RHD will take center stage.

In 2018, the 71st World Health Assembly, the governing body of the World Health Organization, adopted a resolution on rheumatic fever/RHD emphasizing the need to treat RHD as a health priority. The resolution seeks to ensure access to primary and secondary prevention; timely and appropriate diagnosis and treatment of GAS infection, acute rheumatic fever and RHD; and strengthen data collection.

"When the WHO announces that something is high priority, it provides more of an impetus to get it on countrywide and local agendas," relates Taubert. "We were overjoyed with the resolution in 2018, but just as things were starting to take off, up pops COVID."

Still working to make progress, the WHO reported in its 2021 update on the resolution that they are developing a guideline on the prevention and management of rheumatic fever and RHD for use by Member States.

"With this WHO resolution, the role of the WHF is to monitor its implementation and try to bring players together, gain political and financial support, and see where we can offer support and help move the needle," says Mwangi.

One pillar of the WHF's efforts in stemming RHD includes awareness campaigns to prevent and treat symptoms such as sore throat, joint pain and fever. They include programs advocating for antibiotics to be widely available and affordable, as well as for cardiac care for advanced cases.

A campaign called Colours to Save Hearts is a partnership the WHF developed and launched in Mozambique, a country with an estimated 3% incidence of RHD among school-aged children, one of the highest rates in sub-Saharan Africa. Coloring books and crayons are distributed in schools around the country to children aged six to 13 years to help them learn about RHD and how to prevent it.

In conjunction with this, teachers are being trained to administer strep A tests and local health professionals are being trained in early screening. WHF has allocated a portion of the campaign's funds for capacity building and for surgeries to repair or replace damaged heart valves in patients.

The Colours to Save Hearts program has a goal of educating 60,000 children over two years and thereby indirectly reaching their families such that they impact an estimated 200,000 people.

They are also training up to 25 health care professionals each year in the screening, diagnosis, management and monitoring of sore throat, rheumatic fever and RHD.

RHD Treatment Considerations

The cornerstone of rheumatic fever recurrence and RHD prevention is penicillin. Secondary prevention with benzathine penicillin G (BPG), a long-acting penicillin salt administered as a deep intramuscular injection, has a class I indication and should be given for a prolonged period to prevent recurrent GAS infection and worsening of RHD.

"BPG is quite challenging," says Mwangi. "It's not an injection that people like to give because it's extremely painful to receive, and it must be given every three or four weeks into the backside of children." WHF and other organizations have advocated for reformulation of the drug because reluctance is so high.

"Ten years of prophylaxis is recommended or until age 40 years. But there are situations where even as people get older, say, they're taking care of grandchildren or teaching, where they are at risk for repeated exposure to Strep A and need to stay on BPG or go back on prophylaxis for life," says Taubert.

Individuals with mild or asymptomatic RHD have the most to gain from secondary prophylaxis because, in the absence of acute rheumatic fever recurrence, the majority will have no detectable disease within five to 10 years.6

Rheumatic valve disease is the primary cause of mitral stenosis, with anatomic features reflecting this disease process. This makes echocardiography screening to detect asymptomatic cases an attractive strategy, which was the impetus behind the 2012 WHF criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of RHD. These guidelines are being updated.

Given that RHD is the most common cause of mitral valve stenosis worldwide, the echo criteria are also important for determining which patients are most likely to benefit from balloon mitral valvotomy.

A Classic Case: A Woman Walks Into an ED

In the U.S., pregnancy can be the event that triggers the unmasking of a history of RHD and send a woman, often an immigrant, to the emergency department (ED) in distress. Cardiology talked with a leading expert in cardio-obstetrics, Yonatan Buber, MD, FACC, about the presentation and management of such a case. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and the associate program director of the Seattle Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program, Cardio-Obstetrics Program.

The Case

A 27-year-old woman presented to the ED in Seattle with gradually worsening dyspnea on very mild exertion. She recently learned she is pregnant.

The patient is from Nigeria and immigrated with her family six months ago. She is generally healthy and her history is unremarkable other than for a "heart murmur" that she was told about by a primary care practitioner during her teenage years. This is her first pregnancy. On questioning, she recalls a bout of illness when she was younger, with symptoms consistent with rheumatic fever (fever, joint pain, fatigue). She has never seen a cardiologist, nor had an echocardiogram.

On examination, she was found to be in pulmonary congestion. On cardiac auscultation there was a diastolic murmur and an opening snap heard early after the second heart sound. The labs showed only mild anemia, in proportion with her stage of pregnancy. There was moderate pulmonary congestion on chest x-ray.

The echocardiogram showed classic findings of severe rheumatic mitral valve disease, with a mean diastolic gradient across the mitral valve of 16 mm Hg, and a dilated left atrium. Ventricular function was normal and she had moderately elevated pulmonary artery (PA) systolic pressures estimated at 40 to 45 mm Hg. Her ECG showed she was in sinus tachycardia at 110 beats per minute, with signs of left atrial dilation.

Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) was consulted, and a fetal ultrasound showed the baby to be in the 50th percentile of growth.

The Discussion

How would you treat this woman?

Buber: We would start by slowing down her heart rate with a beta-blocker and diuresing her with a loop diuretic, typically furosemide. Sometimes, digoxin can be added if needed if a patient is in atrial fibrillation (AFib) and cannot be cardioverted until a left atrial thrombus is excluded or in the presence of one. But if possible we prefer to just use beta-blockers. The goal resting heart rate is <90 beats per minute, sufficient to allow adequate diastolic filling of the left atrium and prolonged ejection time into the left ventricle to decrease mean diastolic gradients.

While our goal is to keep the patient euvolemic, we prefer slight hypovolemia over hypervolemia. However, it's important to balance the reduction of volume overload against the reduction in placental blood flow associated with diuretic medications. Usually, with just those two medications, we see good initial symptomatic control and a meaningful decrease in the diastolic gradients and left atrial pressure.

If the patient is not sufficiently responsive to these medications, what's the next step?

Buber: If we don't see an improvement in symptoms and a reduction in diastolic gradients, our next step is to consider a percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy (PBMV) to increase mitral valve area and reduce transmitral gradients, thereby helping the patient be more resilient to the hemodynamic load of pregnancy. In the 2020 ACC/AHA Valvular Heart Disease Management Guideline, PBMV has a class I indication for a mitral valve area <1.5 cm2 and symptoms in pregnant women (and in asymptomatic women before pregnancy).1

During pregnancy, we try avoid a PBMV procedure before the second trimester. During the second trimester, most of the fetal organs are formed and the baby's thyroid gland has not started to function yet, so there's low risk of fetal thyroid toxicity. The other reason the second trimester can be sort of an ideal time to intervene is the lower chance that the mother might go into active labor and smaller uterine volume, so there is a greater distance between the fetus and the chest than in later months.

Let's say she's controlled on beta-blockers and diuretics, what happens as the pregnancy progresses and the hemodynamic stress on the heart worsens?

Buber: If the patient responds well to medical treatment, we usually have her go home and return for regular echocardiographic follow-up, about every four weeks, or less frequently if the gradients are lower. MFM will also monitor the baby with regular fetal ultrasound.

As the hemodynamic stress on the heart increases, the heart rate often starts to creep back up. If this happens, or if the symptoms or echocardiographic findings worsen, we'll increase the beta-blocker dose. Pregnancy is notorious for being a time when beta-blockers are incredibly well metabolized, so we expect to need to go to very high doses to get good heart rate control. We sometimes get to mega doses, like 100 mg of metoprolol TID, which is unheard of for someone who is not pregnant.

Are there risks to the fetus?

Buber: Beta-blockade and diuretic use are both associated with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm birth especially when given at high doses, which of course we have to weigh against the risks to both mother and fetus associated with severe valve disease. Atenolol has been shown to be associated with more IUGR, so it's contraindicated in this setting. It is the only beta-blocker that is given a risk class "D" by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, meaning there is demonstrated human fetal risk.2 But IUGR pretty much happens in all cases to some extent, which is why we also monitor the baby with fetal ultrasound.

Would you recommend this patient carry to term or deliver early? What kind of delivery is optimal?

Buber: It's very individual. If the mother continues to tolerate pregnancy well and we're able to control her heart rate, the pregnancy can go to term. We generally don't like these patients to go into spontaneous delivery, especially if the family lives far from the hospital. We allow for induction if it's needed at around 39 or 40 weeks.

We now know that Cesarean deliveries put more strain on the heart. The outcomes for women with heart disease who undergo Cesarean delivery are worse than with a vaginal birth. Therefore, we rarely opt for a Cesarean delivery. We ensure there is good pain control during delivery and the approach is an assisted second-stage delivery, in which either forceps or a vacuum delivery is used to avoid too much Valsalva maneuvering and contractions with the associated autotransfusion.

What are the worries during delivery?

Buber: There are two concerns during delivery. One is the onset of pulmonary edema and the other is onset of AFib, because of the repeated Valsalva maneuvers and the autotransfusion of blood from the placenta during each contraction. Pulmonary edema and AFib may occur almost simultaneously by triggering one another. So, once the patient loses the atrial kick because they go into AFib, that also facilitates them going into pulmonary congestion and edema. Either or both of these may mean that we need to intubate the patient and perform cardioversion during delivery. Cardioversion is relatively safe for the mother and the baby, but it's not an ideal scenario.

What happens after delivery?

Buber: We often see hemodynamic derangements and arrhythmias in the first few days after delivery, as blood volume returns to normal and there are acute hormonal changes. For example, with each uterine contraction, we can see 400 to 500 ccs of autotransfusion back to the heart. A healthy, normal heart is able to deal with the changes. However, for a woman with valvular disease, we can see volume overload and arrhythmias that require treatment. We now recommend women with valvular heart disease of moderate severity or higher to stay in the hospital for four or five days after delivery.

How many pregnant women with RHD do you tend to see a year?

Buber: Last year we cared for 12 women who were pregnant and had RHD. Two of them underwent a catheterization procedure during their pregnancy because their gradients were extremely high. The others were managed medically.

As per guidelines, these women should ideally be treated in a tertiary care center with a specialized cardio-obstetrics service, like mine in Seattle, which includes a dedicated multidisciplinary team of cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and maternal-fetal medicine obstetricians with expertise in the management of high-risk cardiac conditions during pregnancy.

What are the other notable presentations of RHD in pregnancy?

Buber: The ROPAC Registry of pregnancy and cardiac disease offers important information from the largest prospective cohort of pregnant women with RHD to date.3 This registry with 390 women with RHD and no valve replacement before pregnancy revealed a few things: mitral stenosis with or without mitral regurgitation (MR) was seen in 273 women and isolated MR in 117. Women with mild (20.9%) or asymptomatic mitral valve disease tended to tolerate pregnancy fairly well, but in those with moderate (39.2%) or severe (19.8%) mitral stenosis, heart failure was seen in 23.1%. Maternal death during pregnancy was seen in only one patient with severe mitral stenosis.

The other presentation we see fairly often is women with RHD who had their mitral valve replaced. We prefer to see a bioprosthetic valve over a mechanical valve in these women, because it is associated with a lower risk of valve thrombosis, bleeding, and fetal or maternal death. As per the guidelines, women with mechanical heart valves considering pregnancy should be counselled that pregnancy is high risk and no anticoagulation strategy has been shown to be consistently safe for both the mother and baby.

Yet, we do see women in our clinic who have a mechanical mitral valve; often they have immigrated to the U.S. The main issue is that warfarin is teratogenic in the first trimester of pregnancy if given at anything higher than a very low dose, such as 5 mg a day. But it's rare that such a low dose is sufficient to manage these patients. Often, we need to switch them to enoxaparin and teach them how to inject it. In 2021, we had three such patients with mechanical mitral valves who were successfully treated.

We had one very sad case of a woman who came from Kazakhstan who had been managed in her home country with warfarin for a previous pregnancy. We tried to switch her to enoxaparin, but neither she nor her husband was comfortable with giving the injection and she continued on high-dose warfarin. The fetus had a brain bleed and the pregnancy had to be terminated.

Shifting to severe mitral stenosis in RHD in general, not specific to pregnancy, what is the duration of a balloon valvotomy and can it be redone?

PBMV is recommended in symptomatic patients with severe rheumatic mitral stenosis and a mitral valve area ≤1.5 cm2 (Stage D) and favorable valve morphology with less than moderate (2+) MR. Contraindications are a left atrial thrombus on transesophageal echo or more than moderate MR and we would not do the procedure.

There's a direct correlation between how favorable the valve is for intervention and its duration. There have been two larger studies on this. One from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute showed freedom from death, mitral valve surgery and repeat valvuloplasty of about 80% at one year, dropping down to 60% at four years. In a second study, rates of reintervention were about 40% at 12 years.

In terms of a repeat procedure, the same rules apply as doing it the first time. The Wilkins score as well as contraindications would be determined. Depending on these, it is possible. Generally, acute and long-term survival from a second procedure are a little bit lower than with a first procedure.

References

- Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:e25-e197.

- Halpern DG, Weinberg CR, Pinnelas R, et al. Use of medication for cardiovascular disease during pregnancy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:457-76. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.075.

- van Hagen IM, Thorne SA, Taha N, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with rheumatic mitral valve disease: Results from the registry of pregnancy and cardiac disease. Circulation 2018;137:806-16.

Predicting Outcomes of Balloon Mitral Valvotomy: Which Patients Benefit Most?

Balloon mitral valvotomy (BMV) using transcatheter techniques was developed in the early/mid-1980s and rapidly became first-line intervention for patients with symptomatic mitral stenosis. But which patients are the best candidates? To predict the outcome of BMV, Wilkins and colleagues reported that the appearance of the mitral valve on the pre-BMV echocardiogram predicted immediate outcomes.1 The valve is "scored" from 1 (best) to 4 (worst) based on four factors: leaflet mobility, leaflet thickening, subvalvar disease and calcification – for a total of 4 to 16.

Mitral valve area, left atrial volume, transmitral pressure gradient, pulmonary artery pressure, cardiac output, cardiac rhythm, NYHA functional class, age and sex were also studied. Because there was some increase in valve area in almost all patients, the results were classified as optimal or suboptimal.

Suboptimal outcomes were defined as a final valve area <1.0 cm2, final left atrial pressure >10 mm Hg, or a final valve area <25% greater than the initial area. The best multiple logistic regression fit was found using the total echocardiographic score alone. Patients with total valve "scores" <8 are the best candidates for BMV and can expect good long-term results. Those with "scores" >11 have worse outcomes. Patients with intermediate scores may also have good outcomes depending on the distribution of the "score."

In general, severe calcification of the mitral leaflets and restrictive, thickened subvalvar disease do not respond well to BMV. Not surprisingly long-term outcomes are predicted by age and post-BMV variables such as mitral regurgitation, mean final gradient and pulmonary pressure.

Multiple other "scores" have been proposed and can be used successfully. Most use additional quantitative variables such as maximal leaflet excursion from the annulus in diastole or commissural area measurements. However, the appeal of the so-called "Wilkins Score" and its widespread use lies in its simplicity and ease of completion.

Remember that all "scores" are somewhat objective and may overlook factors in individual patients. Take, for example, a patient with isolated severe calcification of the mitral commissures, or irregular calcification of the anterior leaflet. The former may respond minimally to BMV since commissural "splitting" is the mechanism of successful BMV; the latter may end up with severe mitral regurgitation through a torn segment of the anterior leaflet. In such patients, careful sequential balloon up-sizing often produces a good result. Although many patients with high valve scores may benefit from BMV, overall, long-term outcomes are not as good. For most patients with high scores >11, a surgical approach should be considered by the Heart Team. But for patients with serious comorbidities or other risks for surgery who have high echo scores, BMV may still provide hemodynamic benefit and symptom relief for a time.

Reference

- Wilkins GT, Weyman AF, Abascal VM, Block PC, Palacios IF. Percutaneous balloon dilatation of the mitral valve: An analysis of echocardiographic variables related to outcome and the mechanism of dilatation. Br Heart J 1988;60:299-308.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global Burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2982-3021.

- Zühlke LJ, Beaton A, Engel ME, et al. Group A streptococcus, acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: Epidemiology and clinical considerations. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2017;19:15.

- Watkins DA, Beaton AZ, Carapetis JR, et al. Rheumatic heart disease worldwide: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1397-1416.

- de Loizaga SR, Arthur L, Arya B, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in the united states: Forgotten but not gone: Results of a 10 year multicenter review. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e020992.

- Hawkins RB, Strobel RJ, Mehaffey JH, et al. Contemporary prevalence and outcomes of rheumatic mitral valve surgery. J Card Surg 2022;37:1868-74.

- Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297-309.

- Pfoh E, Wessels MR, Goldmann D, Lee GM. Burden and economic cost of group a streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics 2008;121:229-234.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Valvular Heart Disease, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Quality Improvement, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Heart Valve Diseases, Heart Failure, Social Determinants of Health, Health Equity, Heart Defects, Congenital, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Pregnancy, ACC International

< Back to Listings