Cover Story | Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy: Helping Patients Help Themselves

Vaccine hesitancy – the reluctance or refusal to receive a vaccine despite its availability – is nothing new. Hesitation and even opposition to vaccines began shortly after the introduction of the smallpox vaccination in the 1800s and have continued ever since. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) listed vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to global health back in 2019.

The reasons for vaccine hesitancy are varied. For some, a fear of needles, concerns about missing work, or anxiety regarding side effects are behind decisions to delay or avoid a vaccine. For others, the reasons can be more complex and tied to deep-seated spiritual, religious, philosophical and/or political beliefs of individuals, thus making conversations about vaccines all the more difficult.

While the debate over vaccines hasn't waned over the last two centuries, the COVID-19 pandemic has definitely brought it to the forefront as death tolls from the virus continue to rise and countries around the world continue to roll out the vaccine. According to Our World in Data, only about 44% of the world population had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of September, with the vast majority of vaccinated individuals living in higher-income countries. Only 2% of people living in low-income countries have had at least one dose of the vaccine. Meanwhile, the global death toll has reached more than 4.5 million and counting.

Outside of access to the vaccine – which is clearly one of the top reasons for low vaccination numbers, particularly in low-income countries – vaccine hesitancy is another major contributor. Concerns about the safety of the vaccine, given the lack of long-term data and the speed of development and authorization for use, are often cited. For example, more than one-third of unvaccinated individuals in the U.S. believe risks from the vaccine are greater than the risk of COVID-19, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Similarly, a recent poll conducted by the de Beaumont Foundation found that one-third of nearly a thousand unvaccinated adults said full approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would address all or most of their concerns about the vaccines' safety, while another 20% said it would address some of their concerns.

Religious beliefs, concerns about government mandates on health care decisions and civil liberties, and lack of public trust in government and research, especially among certain racial and ethnic groups, are also playing a role in the vaccine debate. Layer on complacency with the status quo and all the misinformation and disinformation (i.e., alteration of DNA myths and microchip and 5G conspiracy theories) that are easily propagated and spread through social media platforms and the internet, and there's a powerful vortex that continues to keep too many individuals on the sidelines, not getting vaccinated.

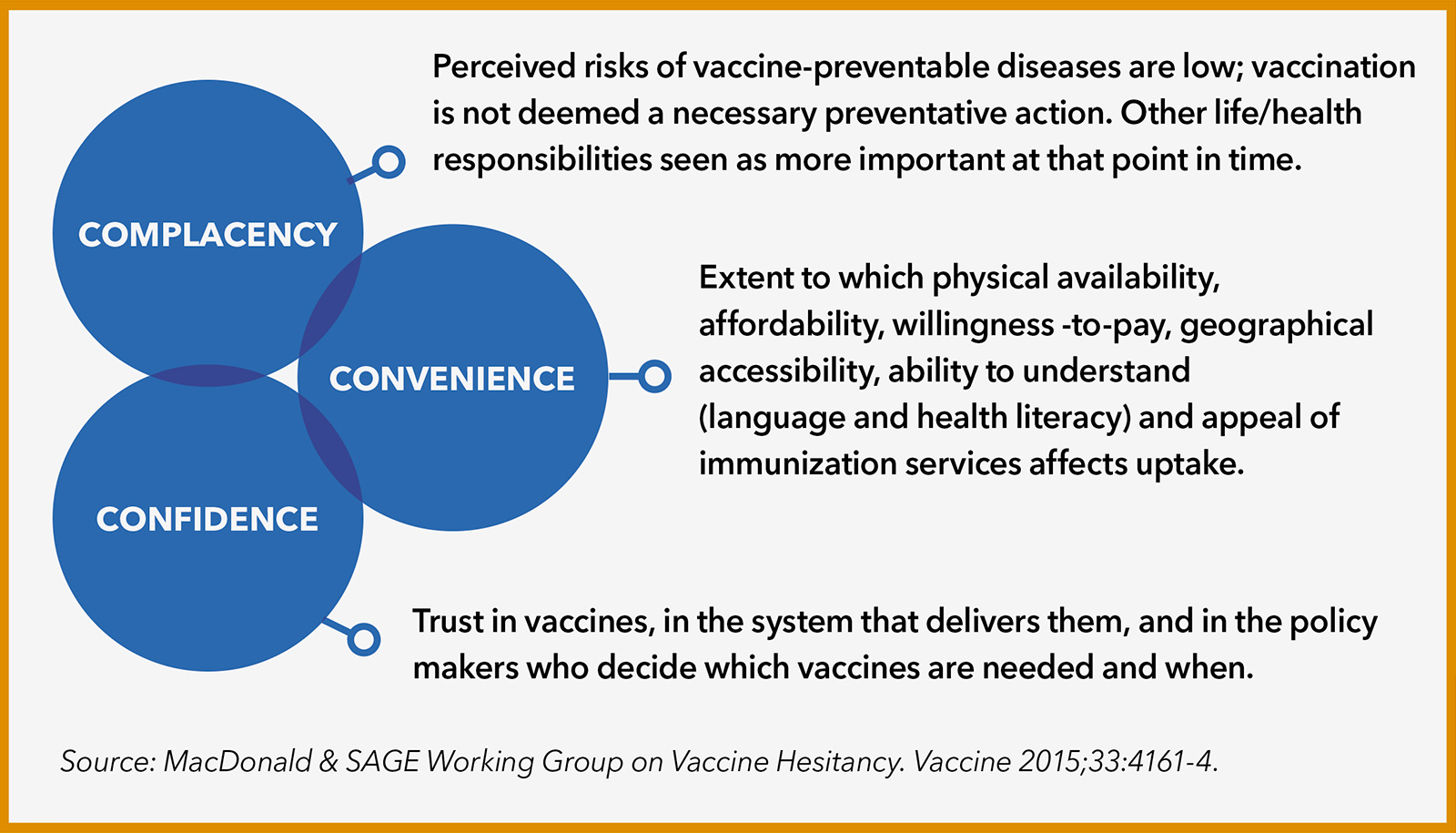

Understanding the "3 Cs" Model of Vaccine Hesitancy

The "3 Cs" model outlines how complacency, confidence and convenience play into vaccine hesitancy. Addressing concerns within these domains can help with moving patients along the spectrum from resistance or hesitancy to accepting a vaccine.

Who Do You Trust?

How do we solve for this dilemma, given the very real scientific evidence showing the ability of the vaccine to save lives, reduce hospitalizations and slow the spread of the virus? Enter the role of health care providers, who are viewed as trusted sources of information when it comes to decisions about vaccines, disease management and overall health.

Vaccine Education Resources For Patients

ACC's CardioSmart initiative includes infographics and other patient tools in multiple languages to help educate heart patients about COVID-19 and the importance of vaccines. Find out more.

Greater Than COVID is a public information initiative led by the Kaiser Family Foundation that provides Vaccine FAQ videos featuring a diverse range of physicians, nurses, community health workers and trusted leaders answering questions about the COVID-19 vaccine, including new variants, safety and why young healthy people need it too. Videos are also available in Spanish. Find out more. Find out more.

FDA Vaccine Information is available on the FDA website in a number of languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Korean, Tagalog and Somali. Find out more.

The Vaccine Confidence Project started a decade ago to monitor public confidence in immunization programs and provide analysis and guidance for early response and engagement with the public. Scan the QR code for polling and resources. Find out more.

"The government and the media have tried to encourage people to get a vaccine. Yet, many times patients want to hear directly from their own caregivers about the risks and benefits of having a vaccine," says Ami Bhatt, MD, FACC, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital's Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program in Boston. "Having the discussion with somebody in the medical field who knows them and who recommends the shot was more than enough to convince many of my patients to get a vaccine," she says.

This trust in health care providers hasn't been lost on groups like the WHO, which have made it a priority to help increase public trust in health care clinicians and health systems to combat misinformation and improve patient outcomes – whether it's combatting COVID-19 or dramatically reducing noncommunicable diseases like cardiovascular disease and cancer, which account for 71% of all deaths globally.

"At times it can seem like a daunting task to even ask a patient if they have been vaccinated or to test the waters about their willingness to discuss why not and engage them in a conversation that may help them make a different choice," says Bhatt, "but with the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines stalling, and the numbers of people infected and dying, it's falling to individual conversations between clinicians and patients to move the needle, one at a time."

Gladys Velarde, MD, FACC, professor and medical director of the Women's Cardiovascular Heart Program at the University of Florida in Jacksonville, agrees. "It's critical that cardiologists talk with their patients about vaccine hesitancy," says Velarde, noting the need to treat the whole patient, not just one condition. "When I speak with patients, I make it very clear their chronic conditions could lead to a worse outcome if they get infected."

Diverse Populations, Diverse Concerns

COVID-19 and Asian Americans

The high morbidity and mortality rate associated with Asians and COVID-19 is probably a combination of many different factors," according to Yang, who is also a member of the global faculty of the Stanford Center for Asian Health Research and Education.

He notes that some comorbidities like hypertension or high cholesterol are more prevalent in certain Asian subgroups, which could put those specific groups at higher risk for death or hospitalization from COVID-19. He also points out that Asian Americans, similar with Latinx communities, are likely to have increased COVID-19 exposure because many live in crowded multigenerational housing. Unique to the Asian American population, 20% of individuals live in a household with at least one health care worker, which also means greater exposure to the virus.

While the good news is that Asian Americans broadly have a relatively high vaccination rate – they make up 6% of the population and they have received 6% of vaccines – poor quality data and a lack of disaggregated race/ethnicity data are obscuring COVID-19-related disparities.

"The key problem is that Asians are lumped together in one group, and the impact of COVID-19 and vaccination rates are much more subtle than that," says Yang. He hopes that future data collection can be expanded to better understand the subtleties across Asian populations and better target and manage care and vaccination efforts.

In both the Latinx and Black communities, the rates of risk factors, comorbidities and cardiovascular disease are higher compared with Whites. "While COVID-19 didn't cause these underlying disparities, it unmasked and revealed them because it placed these patient populations at higher risk," says Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, FACC. Death rates from COVID-19 were ninefold higher in Blacks than Whites in March 2021, while they were fourfold higher for American Indians and Alaska Natives and threefold higher for Latinx Americans.1

Meanwhile, vaccination uptake for COVID-19 in these communities continues to be lower, compared with Whites. While there are some signs of a recent uptick in vaccination rates across all racial and ethnic groups, the rates of vaccination still fall far short in relation to the share of COVID-19 infection in most of these communities.

What are some of the reasons behind these trends? Within the African American/Black community, a long-standing mistrust of orthodox medicine is a major barrier to accepting vaccinations, says Ferdinand. The Tuskegee syphilis study, where Black men were deliberately not treated for syphilis for research purposes, and the infamous case of Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells were used by scientists without her knowledge, are two prominent drivers of this mistrust.

Velarde notes a similar widespread mistrust of the government and the medical system within the Latinx community, in addition to frequent language barriers and often limited access to regular care. "The Latinx community uses a lot of social media, which has been inundated with misinformation that creates mistrust and fear," she says. For example, misinformation about proof of citizenship requirements has held undocumented workers back from vaccination, while rumors about fertility impacts, DNA alteration and microchips are also adding to vaccine hesitancy in this patient population.

Language barriers and lack of information about the vaccine, rather than misinformation, is a common problem in Asian communities that are also disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, says Eugene Yang, MD, FACC, professor of medicine and Carl and Renée Behnke Endowed Professor for Asian Health at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. More recently, concerns about hate-related violence have also meant many Asian Americans are afraid of leaving their homes or communities out of fear of being attacked. Research from the Pew Research Center published this past March said 26% of Asian Americans surveyed feared being threatened or attacked in the last year.

Personalizing Solutions

When Ferdinand met recently with a younger, Black immunocompromised patient the first question to the patient was whether he'd been vaccinated for COVID-19. Because the patient was at high risk, addressing an immediate barrier to his ongoing health came before the usual cardiac evaluation, Ferdinand says.

As with all his vaccine-hesitant patients, Ferdinand, a cardiologist and professor of clinical medicine at the Tulane University Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans, listened without judgment to the man's fears and then was able to engage in a conversation and provide important resources on the vaccine's safety, as well as the very real risks of death should the patient remain unvaccinated and be diagnosed with COVID-19. "I think understanding the potential impacts on his life and his family helped him to recognize the need to protect himself and get vaccinated," he says.

Ferdinand, who is also a member of the National Institutes of Health's Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) Against COVID-19 Disparities and the Louisiana COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force, also shares with patients the South African concept of Ubuntu, which recognizes that everyone within a community is connected. "Although there seems to be a concept afloat that whether or not to get vaccinated is one's personal choice, in reality, with infectious diseases, it's everyone's business. This is especially true for coronavirus infections that are spread through droplets and aerosols and prolonged contact." According to Ferdinand, when individuals are able to recognize that the disproportionate rate of hospitalization and death are real, not imagined, they are more willing to see the value and the role they can play in helping themselves, their families and their community.

Health care providers working in tandem with community leaders and organizations have also proven to be successful tactics in reaching Black, Latinx and Asian communities. Yang notes that community events to book appointments have been successful in overcoming technology and language barriers and reaching specific Asian communities across the country, such as Hmong communities in Minnesota or Korean communities in Seattle.

Community partnerships can also help provide translating services and/or distribute information where people live, work, worship and play. Yang notes that when he sees vaccine-hesitant patients who don't speak fluent English, he makes sure to rely on translators and to hand out information sheets in their native language.

Velarde uses similar tactics with her Latinx patients. She was one of the first in Florida in line for the COVID-19 vaccine and shares that photo of herself in the newspaper with her patients and during Spanish-speaking community vaccination events where she's a volunteer. She takes the time to listen to and address the concerns of those who are hesitant about vaccination and has handouts ready to give them to take home.

If a patient agrees to get a COVID-19 vaccine, Velarde arranges for a medical assistant to take the patient to the hospital's vaccination clinic directly after the visit. Encouraging patients to get vaccinated is a team effort, she says, and she reminds staff that accompanying someone to the clinic is just as important as taking the patient's vitals.

"Education, education, education, verbal and written, is needed to reach specific populations about the benefit of COVID-19 vaccination," says Velarde. She also urges clinicians not to underestimate the value of community volunteering. "Volunteering shouldn't stop in medical school," she says. "It's important for clinicians to have a wider breadth of knowledge of what it means to take care of our citizens."

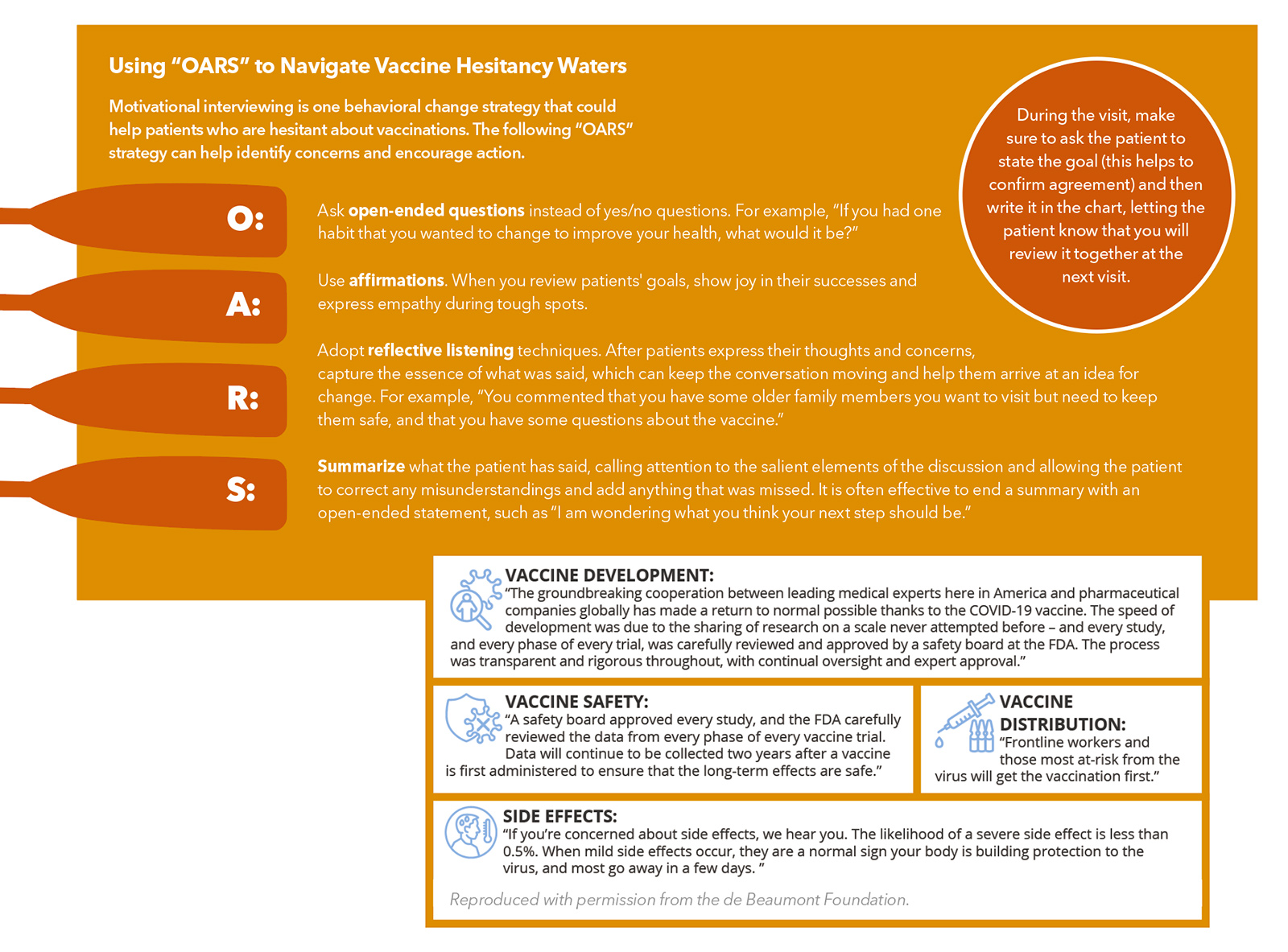

Reproduced with permission from the de Beaumont Foundation. Find this and more at debeaumont.org/changing-the-covid-conversation.Toolkit For Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy: Helping Patients Help Themselves

Tips to Address Vaccine Hesitancy

- Listen patiently, without judgement, and let patients know it's legitimate to have concerns and questions.

- Converse, don't lecture, to debunk misinformation with respect, facts.

- Help the patient understand the facts on their terms. Use plain language, not medical or scientific jargon, and leave pauses to allow for follow-up questions by the patient. Remember, health and scientific literacy varies, and help may be needed to put the daily barrage of information into context.

- Talk about the people behind the vaccine, the scientists and researchers, rather than the science of the vaccine and pharmaceutical companies.

- Personalize the conversation to their concerns and what's important in their lives.

- Understand cultural concerns, including perception of risk, low confidence in vaccines, distrust/mistrust of public services, access barriers, sociodemograhics, language. Engage trusted community leaders.

- Talk about protecting their family and community and ending the pandemic for a true return to normal. and returning to normal.

- Help them evaluate the balance between the limited risk with a vaccine against the risk of contracting COVID-19 and the impact of Long COVID Syndrome.

- Share your vaccination story with your patients. Explain the reasons why you decided to get vaccinated and the considerations you weighed to make the decision.

- Assess the need for help with making an appointment for a vaccine or finding a vaccine location (technology, access issues)

- Assess whether concern of proof of citizenship is a concern (Fact: It's not required.)

- Post information in the clinic and on the clinic website and social media platforms and provide handouts in their language to take home.

- It's not one and done. An ongoing dialogue may be needed to move a patient from being hesitant to vaccinated.

- Avoid assumptions. Ask the patient directly about their concerns and motivations and then then tailor the conversation accordingly to share the information that will help them make the right decision for themselves.

- Involve the entire team, including pharmacists.

Resources To Learn More About Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy

Greater Than COVID. A public information initiative led by the Kaiser Family Foundation that provides Vaccine FAQ videos with a diverse range of physicians, nurses, community health workers and trusted leaders answering questions about the COVID-19 vaccine, including vaccines and new variants, safety, and why young healthy people need the vaccine. Videos are also available in Spanish. Learn more here. Access their COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor Dashboard with detailed information by demographics, a daily tracker, and a section on tailoring the conversation to different groups.

Changing the COVID Conversation. A collection of resources, polling and focus groups on overcoming vaccine hesitancy from the de Beaumont Foundation. Access it here.

The Vaccine Confidence Project. Started a decade ago to monitor public confidence in immunization programs and provide analysis and guidance for early response and engagement with the public to ensure sustained confidence in vaccines and immunization. Learn more here about polling and resources.

FDA Vaccine Information. Available in a number of languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Korean, Tagalog and Somali. Get started here.

CDC Myths and Facts about COVID-19 Vaccines. An easy-to-understand listing of common myths – counterbalanced with the facts – that is updated regularly. Start reading here.

WHO Mythbusters. An online compendium of COVID-19 myths and responses for patients, most with downloadable infographics of the facts. Access it here. A wide range of COVID-19 topics are addressed in a number of short videos, available here.

Tip Sheet For Communicating About the FDA Approval to Build Confidence in the Vaccine. Download it here.

CardioSmart COVID-19 Patient Education. Download the infographics here.

Additional Reading

Murdan S, Ali N, Ashiru-Oredope D. How to Address Vaccine Hesitancy The Pharmaceutical Journal 2021;April 13.

Quinn SC, Andrasik MP. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in BIPOC communities – Towards trustworthiness, partnership, and reciprocity. New Engl J Med 2021;385:97-100. [Editor's Note: Included a questions and answers table for train-the-trainer and community education.]

CDC. Talking With Patients About COVID-19 Vaccination. An Introduction to Motivational Interviewing For Healthcare Professionals. Available here.

Stewart E, Fox C. Encouraging Patients to Change Unhealthy Behaviors With Motivational Interview Family Practice Management 2011;18:21-25.

CDC. Vaccinate With Confidence. CDC's Strategy to Reinforce Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines. Available here.

Trust-Building Tips

- Use storytelling. "It's more impactful when a doctor shares what they have witnessed as opposed to talking about what they read in a medical journal or the latest CDC recommendations," says Mark Miller, vice president of communications at the de Beaumont Foundation, which focuses on public health. "It's not about statistics, it's about making it real." It's also not about trying to convert a patient. "If you come across as judgmental or condescending or frustrated then they're going to dig in deeper," he says. Also, choose your words carefully, framing things positively, for example in terms of benefit rather than consequences. Sometimes a single word can make a difference.

- Provide credible resources. For some patients, local sources are trusted more than national ones. And local trusted leaders may be one of the most important partners for overcoming vaccine hesitancy. Steer patients to recognized sources, like the ACC and American Heart Association, and have handouts prepared for them in their language they can take home. Remind patients not all health information on the internet is fact-based, and some is opinion-based dressed up as medically based (for example, an osteopathic physician considered the number one spreader of misinformation on this topic has published over 600 articles that cast doubt on COVID-19 vaccines.)

- Focus on the Middle. Some 10% of people are in the "wait and see" category when it comes to making their decision about getting vaccinated against COVID-19, according to a poll conducted in July by the Kaiser Family Foundation. It's this watchful waiter group that is most open to talking about the vaccine and most likely moveable.

- Know When to Concede. At times, says Bhatt, it's necessary to concede a patient is unlikely to be moved. "Forcing people to see your way is never a way to have that conversation," she says. "Try to understand why they are hesitant and answer their questions to the best of your scientific ability, and then use your rapport to help them come to a place where they are willing to think about it more."

The Power of Real Conversations in a Social Media World

Medical misinformation has long found a home on the internet. Misleading stories on statins are almost as old as the internet itself. Still, the advent of social media materially changed the game. Instead of needing to proactively search for information, networks and algorithms often now push dubious and sometimes downright dangerous information into feeds. Like it or not, we're all part of what social scientists call the information wars, a strange and shadowy entanglement of culture, politics and power, all fought online through information and disinformation. Often the first victim of this virtual fracas is what was once regarded as commonly held truths, an especially grave concern when it comes to scientific or medical facts. How are cardiologists supposed to navigate this larger social phenomenon without getting drawn into the scuffle?

Eric Stecker, MD, FACC, chair of ACC's Science and Quality Committee and a cardiologist at Oregon Health and Science University, has thought long and hard about this problem, likening it to his career-long efforts to encourage his patients to quit smoking. "I start by asking every patient at every visit about their COVID-19 vaccine status, regardless of their personal risk, and take it from there," he says. "Just like smoking, this is something so important to cardiovascular and overall health that it is the responsibility of all of us. We can't just leave it to our primary care colleagues."

If a patient isn't vaccinated, Stecker assesses their level of readiness or resistance. I often raise the issue of social media myself, asking if they've read or heard anything online that worries them," he says. Stecker emphasizes the importance of getting the conversation going and avoiding politicizing the discussion. He's learned to use less-loaded terms like "rumors," "inaccuracies," or "confusion," to help make space for the vaccine-hesitant to modify their thinking.

Sometimes Stecker can tell it's a lost cause. "I know that if I keep pushing I might jeopardize my whole relationship with the patient. Or I spend too much time fruitlessly addressing vaccination to the detriment of other important aspects of their care.

But just as often, acknowledging all the confusion out there makes space for a genuine conversation. Stecker always steers the conversation back to the scientific facts but in a way that humanizes the discussion and leverages the trust he has earned with his patients. "I tell them that I have looked into the issue personally and studied the data. I tell them I believe the vaccine is safe, for myself, for my family and for my patients. I tell them I think it will help keep them safe and healthy," he says. It doesn't work every time, but Stecker is proud to recall when his vaccine-hesitant patients have ultimately gone on to receive the shot. "I know it's more than my effort, but hopefully my effort has made a difference.

Reference

- Quinn SC, Andrasik MP. N Engl J Med 2021;385:97-100.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Anticoagulation Management, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, COVID-19 Hub, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Geriatric Cardiology, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Pericardial Disease, Prevention, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Valvular Heart Disease, Vascular Medicine, Anticoagulation Management and ACS, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Cardiac Surgery and SIHD, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Interventions, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, CHD and Pediatrics and Quality Improvement, Acute Heart Failure, Pulmonary Hypertension, Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Angiography, Nuclear Imaging, Hypertension, Sleep Apnea, Sports and Exercise and Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Sports and Exercise and ECG and Stress Testing, Sports and Exercise and Imaging, Chronic Angina

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Anticoagulants, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Cardiac Surgical Procedures, Metabolic Syndrome, Angina, Stable, Heart Defects, Congenital, Dyslipidemias, Geriatrics, Heart Failure, Angiography, Diagnostic Imaging, Pericarditis, Secondary Prevention, Hypertension, Pulmonary, Sleep Apnea Syndromes, Sports, Exercise Test, Heart Valve Diseases, Aneurysm, Accidental Falls, Aerosols, African Americans, Alaska, American Heart Association, American Natives, Anxiety, Anxiety Disorders, Asian Americans, Attention, Books, Boston, Cardiologists, Cardiovascular Diseases, Caregivers, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S., Clinical Medicine, Communicable Diseases, Communication, Communication Barriers, Community Health Services, COVID-19, COVID-19 Vaccines, Data Collection, Delivery of Health Care, Disease Management, DNA, Empathy, Ethnic Groups, Faculty, Family, Fear, Fertility, Florida, Goals, Government, Habits, Hate, Health Equity, Hospitalization, Hospitals, Hospitals, General, Housing, Hypertension, Immunocompromised Host, Internet, Judgment, Language, Medicine, Minnesota, Morbidity, Needles, Neoplasms, New Orleans, Noncommunicable Diseases, Osteopathic Physicians, Physician Executives, Public Health, Religion, Risk Assessment, Risk Factors, Schools, Medical, Smallpox, Social Media, Technology, Trust, Undocumented Immigrants, United States Food and Drug Administration, Universities, Vaccination, Vaccines, Violence, Volunteers, World Health Organization

< Back to Listings