Business of Medicine | New Year, New Opportunities For Cardiovascular Care Transformation

Embracing the Pandemic as a Disruptor and Innovation Catalyst

The world has experienced a year unlike any other in this generation, putting 2020 in the history books as the year of COVID. As 2021 begins, it's important to take time to consider the long-term impacts from the pandemic on the health care industry and patient care.

Although history books will focus on the pandemic of 2020, the health care industry could, and should, focus on the disruptor of 2020.

A disruptor is defined as something that interrupts an event, activity or process by causing a disturbance or problem. A disruptor can also be a force for good when it causes radical change in an existing industry or market by means of innovation, a concept often highlighted in the business industry but rarely used in conjunction with changes in the health care industry.

The current trajectory of health care in the U.S. is not economically sustainable and not maximally effective. Accordingly, health care leaders and society at large agree change is needed.

As opposed to small, incremental improvements, the health care industry needs a significant disruption. Viewed through the lens of disruption, innovation and care transformation, there is no opportunity for change like the present.

The pandemic has created economic instability for most health care organizations and providers. Other effects include less than desired patient outcomes from poor access; missed care opportunities; worsening of existing health disparities due to lack of resources and technology needed to seek health care; and a burned out health care workforce.

While these challenges aren't new, they've been amplified by the pandemic and there's an increased urgency to implement solutions.

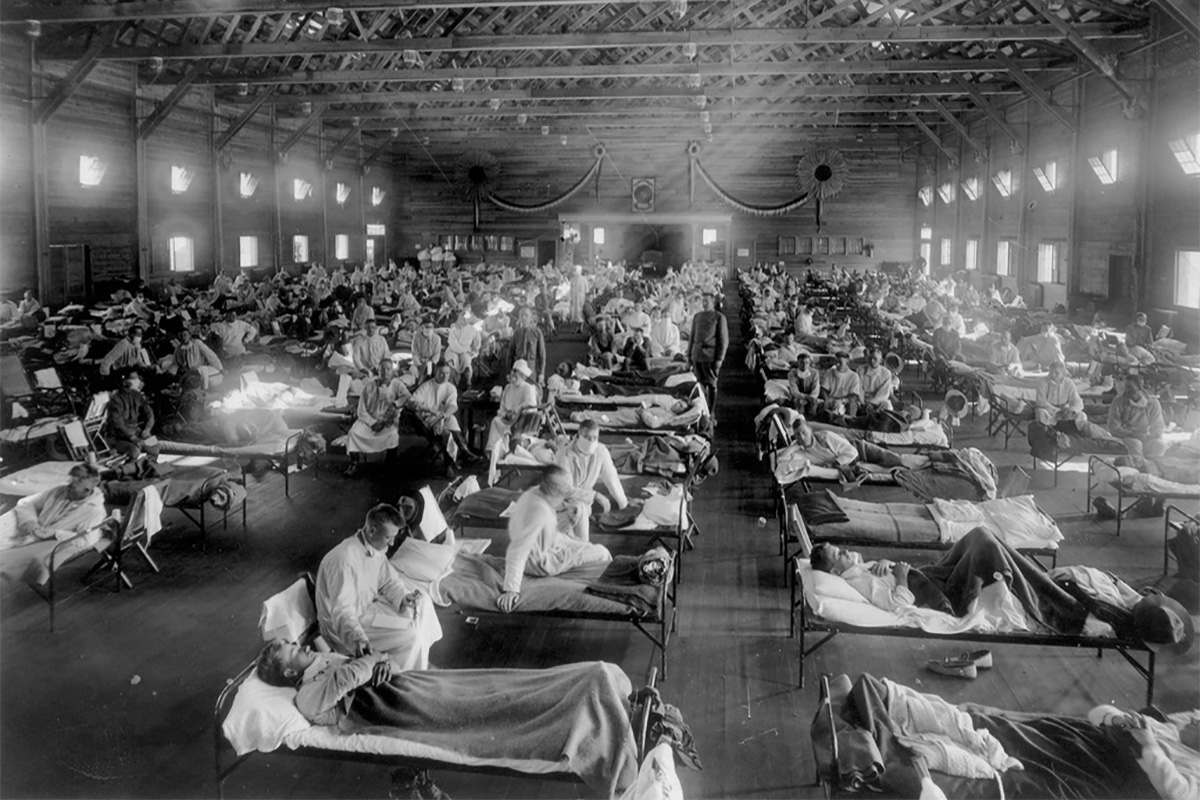

Historical events, such as the 1918 flu pandemic, have provided valuable insights into the effects of a public health emergency, both short- and long-term. From a health care delivery standpoint, many governments embraced new concepts of preventive medicine and socialized medicine after the 1918 flu pandemic.

The U.S. also adopted the employer-based insurance plans that expanded access to health care for the general population.1 Fast forward to the 2020 pandemic and there are many opportunities for innovation in cardiovascular care with hints at transformation, but no clear path to achieving true transformation.

If the 2020 pandemic is not seized as a disruptor and catalyst for innovation and care transformation, it will be a missed opportunity.

Disruption creates a need for action. For some, the action will be to look inward and make changes to do more with less. Others will look externally to see how the disruption has changed the industry and patient and provider needs, and look to innovate and transform to better meet those needs.

A review of this concept in the business industry suggests looking inward often leads to demise, while looking outward can lead to expansion into new services and markets, creating a trajectory otherwise unforeseen.2

Applying Disruption, Innovation to Cardiovascular Care

There is a significant body of literature about leadership in health care. Effective organizations bring the right people to the table with requisite skills in both management and leadership.3,4

Cardiovascular programs need an effective leadership and management structure to provide vision and foster an environment supportive of innovation and transformation. Applied to surviving during a time of disruption, management will tend to concentrate on preserving and improving the status quo, while leadership is about challenging the status quo and creating something different and more effective.5

Where does a program start? Here are three types of innovation described by Regina Herzlinger, Harvard Business school faculty,6 viewed through the lens of the COVID pandemic.

Change the Way Consumers Buy and Use Health Care

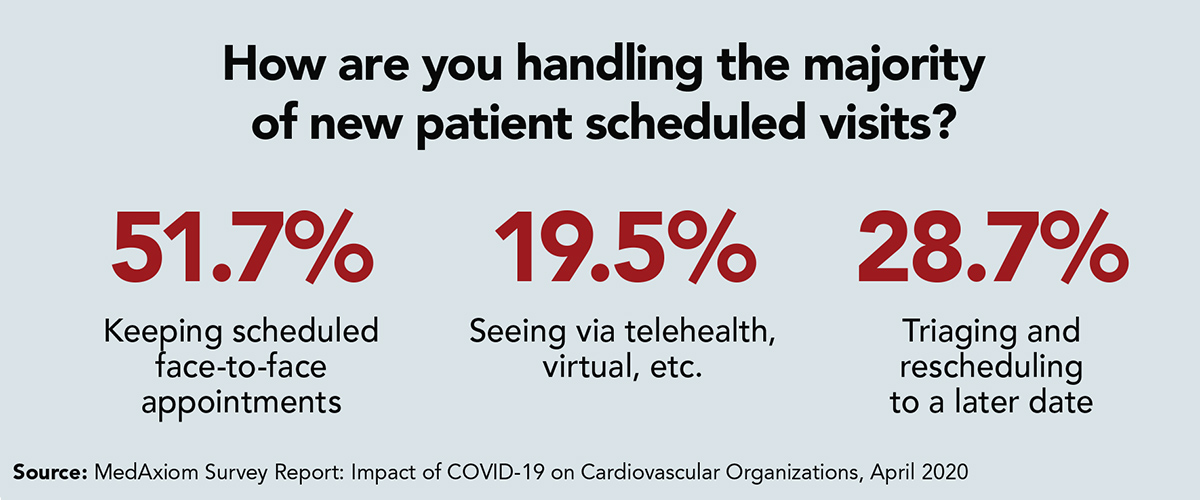

Early in the pandemic, MedAxiom described the rapid transition to virtual care through telehealth services in its "Survey Report: Impact of COVID-19 on Cardiovascular Organizations," published in April 2020.

The survey found most programs transitioned to a virtual delivery model in less than two weeks and changes in reimbursement and regulations that supported the transition closely followed.

Numerous learnings stemmed from the transition to virtual care delivery. The transition highlighted the capabilities and ability to do this work effectively while putting a spotlight on disparities in access to health care. Patients without access to technology had an even harder time receiving needed care.

Further, the early pandemic forced a shift from preventive, routine care to urgent-only care. Many stories have been shared about patients who waited too long to seek care or missed routine evaluations only to present with acute needs.

A shift in the health care delivery model needs to recognize these disparities and assure access to routine, preventive care, as well as urgent needs.

Virtual care worked, and needs to stay, but must evolve. A digital transformation must complement face-to-face care such that virtual care be embedded when and where it is most effective for communication, care coordination and care delivery.

Use Technology to Develop New Products and Treatments

Device therapies, pharmacologic therapies and procedural therapies have all progressed in recent years. Innovations are allowing clinicians to make earlier diagnoses and providing tools for effective primary and secondary prevention.

In coronary artery disease, noninvasive imaging technologies are emerging that provide both anatomic and functional data to better define risk and can guide management strategies. The anticipated result is a shift toward health maintenance with reduced need for, and more effective use of, invasive treatment options.

A recent article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology by Ferraro, et al, provides a disruptive example using the evaluation and treatment of patients with stable angina with a CT-guided algorithm.7

There are many other examples that will have an impact on workforce needs, skillsets, operational processes and changes in both provider and patient expectations. Team-based, multidisciplinary care will promote effective and efficient care.

The pandemic has caused programs to redeploy providers, develop new care pathways and redefine relationships with hospitalists, emergency departments, intensivists and with each other.

This redeployment of providers, which utilizes skillsets in unique ways, was an innovation and proved the cardiovascular industry's ability to adapt. Barriers that were economic and related to "turf" were broken down with ease and grace.

However, solutions to support long-term transitions are required and reimbursement changes and physician compensation models must adjust to support/encourage team-based care delivery.

The work must happen at a pace that will support innovation and a true transformation of care.

Generate New Business Models that May Involve Horizontal or Vertical Integration of Separate Health Care Organizations or Activities

The traditional fee-for-service model is at a tipping point. The pandemic has shown that a reactive care delivery model in a fee-for-service funded environment is ineffective. Limitations to elective procedures, ambulatory care services and overall reluctance to seek health care has created an economic perfect storm for health care organizations.

In addition, nonacute services that utilize acute care hospitals as their site of service came to a halt. This created both economic struggles and more importantly missed care opportunities.

The cardiovascular industry recognizes the opportunity to transition many services to ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) and office/outpatient departments. The pandemic has highlighted that having nonacute care sites of service is important.

An example of a recent delivery innovation in the cardiovascular space is the transition of PCI to an ASC. A position statement from SCAI in May 2020 stated: "the ability to perform PCI in an ASC has been made possible" and is happening effectively when structured appropriately.8

However, full adoption will require multiple changes including health policy, economic alignment, facility planning, integration models and operational structures.

Looking Forward

As tragic as the last year has been, there is an opportunity to use the disruption to create positive, lasting change. Dyad leadership, a vision for innovation and embracing lessons learned will allow true cardiovascular care transformation. Vision and leadership are the key ingredients in the innovations that will transform care.

The ACC and MedAxiom have a joint mission: "To transform cardiovascular care and improve heart health." We are in the business of care transformation and will work tirelessly to lead members with vision, education, organizational resources and advocacy. Let's transform cardiovascular care, together.

Visit MedAxiom.com to learn more about cardiovascular care transformation efforts.

References

- Spinney L. Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed The World. 2017. Public Affairs/Hachette Book Group; New York City.

- Kim WC, Mauborgne R. Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make Competition Irrelevant. 2007. Gildan Media; Prince Frederick, MD.

- Chazal RA, Montgomery MJ. The dyad model and value-based care. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1353-4.

- Fry ETA, Walsh MN. (2018). Cardiovascular health system leadership. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;1: 575-6.

- O'Reilly CA III, Tushman ML. Lead and Disrupt: How to Solve the Innovator's Dilemma. 2016. Stanford University Press; Palo Alto, CA.

- Herzlinger RE. Why innovation in health care is so hard. Harvard Business Review 2006;84:58.

- Ferraro R., Latina JM, Alfaddagh A, et al. Evaluation and management of patients with stable angina: Beyond the ischemia paradigm. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2252-66.

- Box LC, Blankenship JC, Henry TD, et al. SCAI Position Statement on the Performance of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Ambulatory Surgical Centers. Catheterization Cardiovasc Interv 2020;96:862-70.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, COVID-19 Hub, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Interventions and Coronary Artery Disease, Interventions and Imaging, Computed Tomography, Nuclear Imaging, Chronic Angina

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Algorithms, Ambulatory Care, Angina, Stable, Biological Evolution, Cardiology, Communication, COVID-19, Coronary Artery Disease, Creativity, Delivery of Health Care, Emergency Service, Hospital, Family Characteristics, Fee-for-Service Plans, Government, Faculty, Health Care Sector, Health Policy, Health Services Accessibility, Health Services Accessibility, Hospitalists, Insurance, Hospitals, Leadership, Maintenance, Motivation, Organizations, Outpatients, Pandemics, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Patient Care, Public Health, State Medicine, State Medicine, Secondary Prevention, Technology, Telemedicine, Tomography, X-Ray Computed, Health Workforce

< Back to Listings