Pregnancy in Adult Congenital Heart Disease

Quick Takes

- The prevalence of pregnancy in congenital heart disease (CHD) is increasing.

- Maternal complications of pregnancy include stroke, heart failure, and arrhythmia.

- Maternal lesion complexity, unrepaired CHD, and socioeconomic status can predict complication rates.

- Provider awareness, risk stratification, and delivery planning can improve outcomes of pregnancy.

The prevalence of congenital heart disease (CHD) in pregnancy increased by >30% during the 2010s. CHD is now present in approximately 8:10,000 pregnant persons.1 Cardiovascular (CV) diseases such as CHD are major causes of maternal morbidity and mortality, and their increasing presence represents a public health challenge.

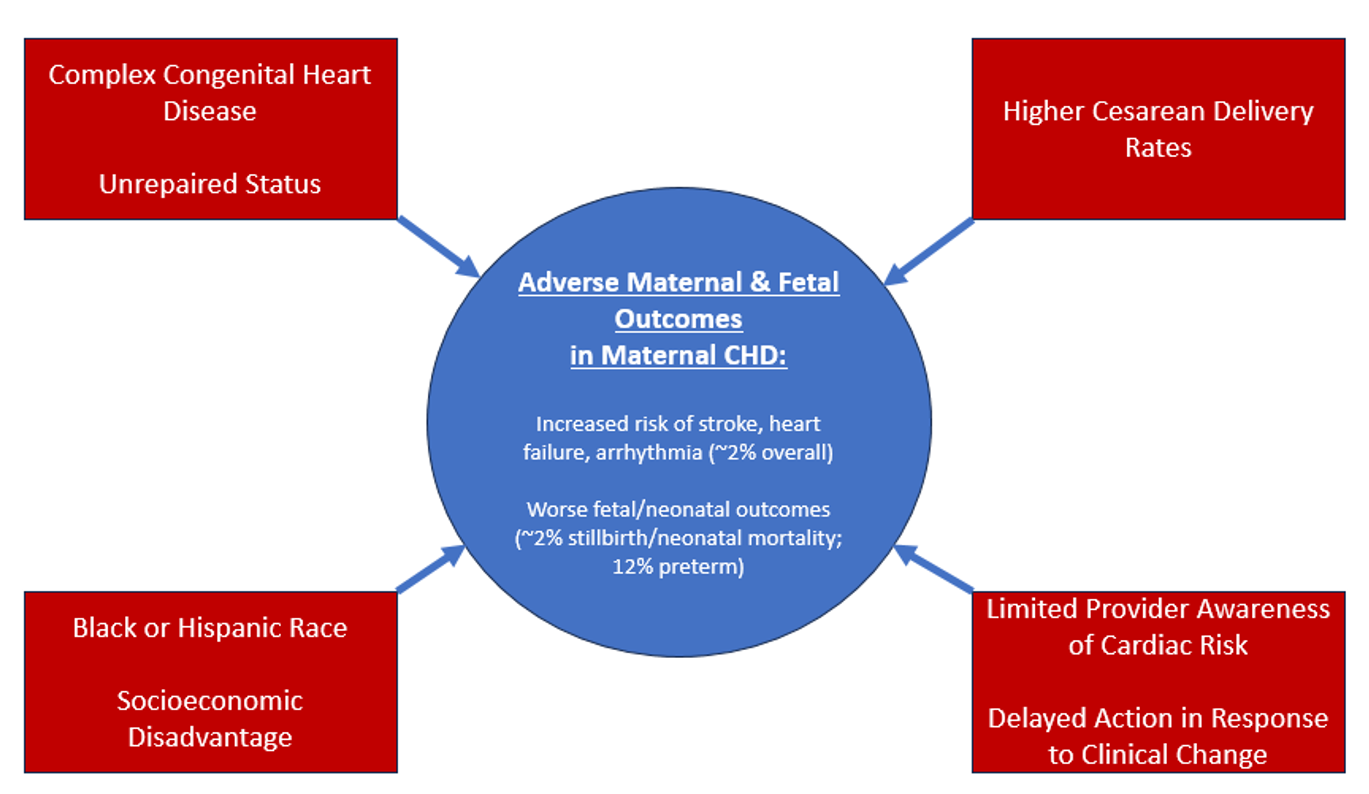

Maternal history of CHD increases the risk of stroke, heart failure (HF), and arrhythmia during pregnancy and the peripartum period.2,3 Although these risks may provoke alarm among providers, the absolute rate of severe cardiac complications in pregnancy complicated by CHD is low, approximately 2% overall. Of note, when care is delivered in an advanced health care system, there is no noted increase in maternal mortality, which remains at approximately 0.15% in the United States.2,3

Neonatal complication rates reflect maternal health status. The incidence of neonatal complications is higher among pregnant persons with CHD than among those without, including increased rates of infant deaths and stillbirths, as well as prematurity and low birth weight.3,4 An analysis of pregnancies with CHD from a German administrative database revealed a 2% combined rate of stillbirths and neonatal deaths, as well as a nearly 12% preterm birth rate.3

Several factors predict complication rates among pregnant persons with CHD and their offspring. Maternal CHD complexity is one such factor; those with more complex lesions experience higher complication rates.3 Unrepaired CHD, compared with surgically palliated CHD, is also associated with worse maternal CV outcomes, particularly if there is history of pulmonary hypertension or HF.4 Data from a multinational registry showed a 0.7% maternal mortality rate and 8.7% incidence of HF in pregnant persons with unrepaired CHD.

Some contributors to poor maternal and fetal outcomes in CHD are modifiable. In a multicenter cohort of patients with heart disease in pregnancy recruited as part of the CARPREG (Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy Study), Pfaller et al. found that approximately one-half of severe cardiac events were preventable. Provider factors accounted for almost three-quarters of the preventable events. These factors included identification and appropriate risk stratification of cardiac conditions, as well as identification and prompt action in response to deteriorating clinical status.5 This result suggests that better education about cardiac risk stratification in pregnancy can reduce adverse events.

Cesarean delivery rates represent another area for practice improvement. Pregnant persons with CHD are more likely to undergo cesarean delivery than are those without CHD.3,6 This delivery method subjects them to higher rates of infection and hemorrhage, among other complications. A group in Boston reported results from a practice in which vaginal birth is planned in all cases of maternal cardiac disease without an obstetric indication for cesarean delivery. Operative vaginal delivery was offered for those experiencing adverse CV symptoms during labor. In that cohort, which included a 66% prevalence of maternal CHD, adverse cardiac outcomes were similar between the two modes of delivery, with lower rates of postpartum hemorrhage in the vaginal delivery group. In this report, vaginal delivery with assisted second stage was undertaken successfully for patients with the well-described higher-risk conditions of severe aortic stenosis and high-risk aortopathy.7 These results provide encouragement for obstetricians and their collaborators to reduce cesarean delivery rates for patients with CHD.

Finally, socioeconomic factors contribute to poor maternal outcomes. In the United States, Black and Hispanic pregnant persons fare worse than others.2 Coming from an emerging country or having public health insurance also correlate with worse maternal outcomes.2,4 These health care disparities warrant corrective action. The health care system in the United States and its providers would benefit from both awareness and specific policies to improve health in these vulnerable groups.

Although maternal CHD increases the risks of maternal and fetal adverse events (Figure 1), appropriate risk stratification, clinical monitoring, and delivery planning—as well as thoughtful public health initiatives—have the potential to improve outcomes for this population.

Figure 1: Contributors to Adverse Outcomes in Pregnant Patients With CHD

References

- Majmundar M, Doshi R, Patel KN, Zala H, Kumar A, Kalra A. Prevalence, trends, and outcomes of cardiovascular diseases in pregnant patients in the USA: 2010-19. Eur Heart J 2023;44:726-37.

- Malhamé I, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Abenhaim HA. Cardiovascular severe maternal morbidity and mortality at delivery in the United States: a population-based study. JACC Adv 2022;1:[ePub ahead of print].

- Lammers AE, Diller GP, Lober R, et al. Maternal and neonatal complications in women with congenital heart disease: a nationwide analysis. Eur Heart J 2021;42:4252-60.

- Sliwa K, Baris L, Sinning C, et al. Pregnant women with uncorrected congenital heart disease: heart failure and mortality. JACC Heart Fail 2020;8:100-10.

- Pfaller B, Sathananthan G, Grewal J, et al. Preventing complications in pregnant women with cardiac disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:1443-52.

- Baris L, Ladouceur M, Johnson MR, et al.; ROPAC Investigators Group. Pregnancy in tetralogy of Fallot data from the ESC EORP ROPAC registry. IJC Congenital Heart Disease 2021;2:[ePub ahead of print].

- Easter SR, Rouse CE, Duarte V, et al. Planned vaginal delivery and cardiovascular morbidity in pregnant women with heart disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;222:77.e1-77e11.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: Cardio-Obstetrics, Heart Defects, Congenital, Pregnancy, Heart Failure, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Cardiac Arrhythmias