Feature | Will it Ever End? Update on Smoking and Cardiovascular Disease

November 15 is the Great American Smokeout. Be prepared to help your patients make it the first day in their journey to a smokefree life. Download and share the Quit Smoking infographic from CardioSmart.org and use these resources – start today!

November 15 is the Great American Smokeout. Be prepared to help your patients make it the first day in their journey to a smokefree life. Download and share the Quit Smoking infographic from CardioSmart.org and use these resources – start today! The good news about cigarette smoking? Its prevalence among adults in the U.S. plummeted from 42.5 percent in 1965 to 15.5 percent in 2015 and fewer adolescents now smoke than ever before.1-3

The bad news? Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S., responsible for an estimated 14 million medical conditions a year, a third of cancer deaths and 150,000 deaths from cardiovascular disease, figures that would be higher if other types of tobacco (cigars, pipes, smokeless tobacco) and secondhand smoke were included.4-6

By now, the connection between smoking and cardiovascular disease is well known. Put simply, smoking significantly increases the risk of and mortality from nearly every cardiovascular disease, often by two- or threefold. Even exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk of stroke and coronary heart disease.7

Yet one study of 737 active smokers found that more than 60 percent did not believe they were at an increased risk for a myocardial infarction.8

In addition to medical repercussions of smoking, the economic effects are staggering. In the U.S.:9

States spend between 6 and 18 percent of their health care budgets on smoking-related conditions.

Smoking accounts for about 1 percent of the nation's gross domestic product. The indirect cost of smoking is responsible for an estimated $151 billion loss in productivity. One analysis estimated that just a 10 percent relative drop in smoking in the U.S. would save an estimated $63 billion (2012 dollars) in related health care costs.10

Quitting: Never as Easy as it Looks

In 2015:

- 68 percent of adult smokers wanted to stop smoking

- 55.4 percent of adults had tried to quit in the past year

- 7.4 percent of adults had recently quit smoking

- 57.2 percent of adults had been advised by a health professional to quit

- 31.2 percent of adults used smoking cessation counseling and/or medication when trying to quit.11

When barely half of adults have been told to quit smoking, and just a third used evidence-based approaches, it's clear that health care professionals can do more to reduce smoking rates.

The most effective approaches for quitting smoking are multifactorial, combining medication (bupropion or varenicline) with counseling or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) plus counseling/support groups.12

Medication is most effective if patients quit smoking within a week of starting bupropion or immediately upon starting NRT. In addition, combining different forms of NRT, such as patch and gum, is more effective than using a single form.13

Nonmedical approaches include smoking cessation phone lines, available in most states; support groups; and cognitive behavioral counseling, among others, according to a JACC Focus Seminar article on the prevention and treatment of tobacco use.7

There's also some evidence that varenicline is more effective than other approaches in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), while a meta-analysis of smoking cessation trials in patients with cardiovascular disease concluded that varenicline and bupropion, as well as individual and telephone counseling, were most effective.14

Cardiovascular professionals are on the front lines when it comes to smoking cessation. More than a third of patients hospitalized for an ACS are smokers, and two-thirds of those who try to quit after their ACS start smoking again within a year.15

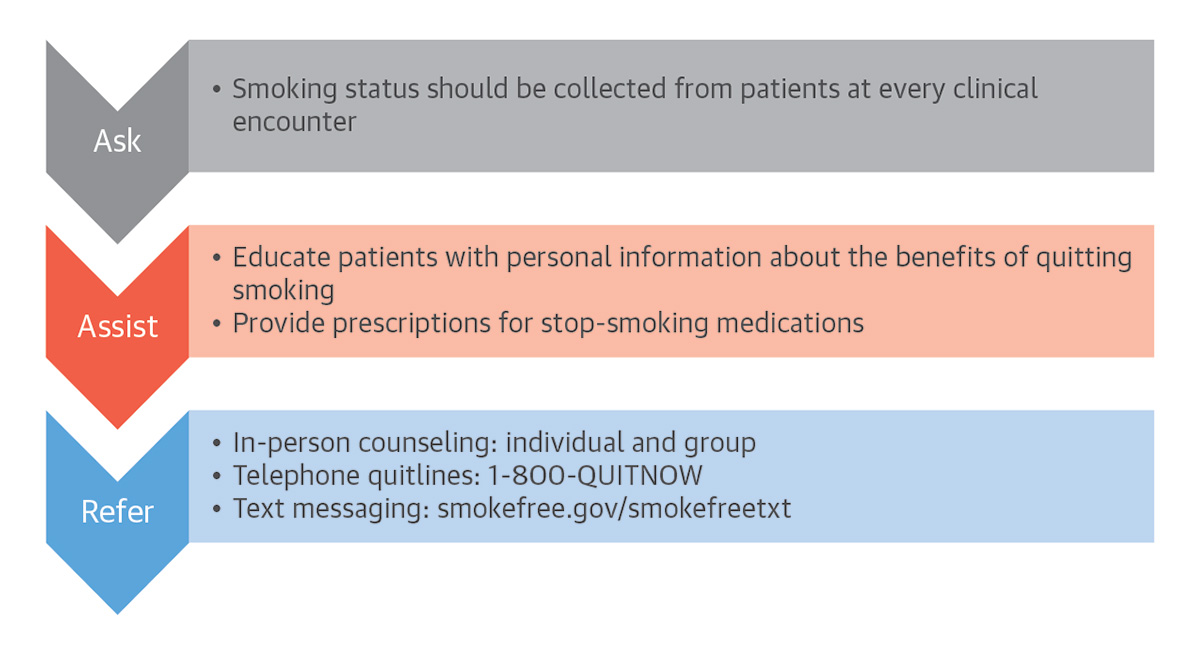

Figure 1: Ask, Assist, Refer

Source: Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1030-45.

Source: Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1030-45.

Given that even a few minutes of advice from a physician can substantially increase the likelihood that someone will successfully quit, it's important that cardiovascular professionals take the time to identify patients who smoke and discuss the potential ramifications and opportunities for cessation. Figure 1 provides a guide that takes just a few minutes to implement during the typical office visit.16

What About e-Cigarettes?

The use of e-cigarettes, which heat a liquid containing nicotine and flavoring to create an aerosol for inhalation, has skyrocketed in the U.S., particularly among adolescents. The most recent government figures find that nearly 11 million youth ages 12 to 17 have used e-cigarettes and similar products which are, in essence, simply nicotine delivery systems.17

In 2017, 2.1 million middle and high school students had used e-cigarettes within the past 30 days, nearly twice the number who smoked cigarettes. Many used two or more tobacco products, which increases their risk of nicotine addiction.17 Their risk is already high given the effects of nicotine on the developing brain.

"While there is debate and uncertainty about the physiologic effects and harms of e-cigarettes, their potential as a "gateway" to cigarette smoking is alarming," says Eric Stecker, MD, FACC, chair of the Smoking Cessation and Prevention Work Group of ACC's Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Section.

Take on Tobacco 21

Almost all smokers begin smoking by age 21. Raising the age at which youth can buy cigarettes and other tobacco/nicotine-related products from 18 to 21, however, can substantially reduce smoking rates22 – and impact a population of nearly 86,783,000 youth.

Thus, ACC supports Tobacco 21 – an effort to raise the legal age to purchase nicotine products to age 21. To date, legislation has passed in more than 340 localities and statewide in California, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Oregon. To become involved:

- Learn more at ACC.org/Tobacco21

- Connect with your state's ACC Chapter

- Contact your state legislators

- Familiarize yourself with Tobacco 21 efforts in your state

- Write a letter to the editor of your local news publications

"I'm proud that the ACC is supporting this effort," says Stecker.

He also praises the efforts of the ACC and the FDA to potentially regulate nicotine levels in cigarettes, with a goal to reduce them to nonaddictive levels. "This could have a profound effect by dramatically reducing the likelihood of children becoming addicted and making it easier for adults to quit," he says.

Indeed, youth who smoke e-cigarettes are six to 10 times more likely to begin smoking tobacco.18

To combat what the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers an epidemic among youth, the agency recently launched a public awareness campaign targeted at this age group, called the Youth Tobacco Prevention Plan. Its three focus areas are preventing youth access to tobacco products; curbing marketing aimed at youth; educating teens about the dangers of any tobacco products including e-cigarettes and retailers about their role in protecting youth.

The FDA is also investigating manufacturers who are accused of illegally marketing to the under-18 age group – and recently took the historic step of issuing warning letters and fines to more than 1,300 retailers and five major manufacturers for their roles in perpetuating youth access to e-cigarettes; they have 60 days to respond with mitigation plans.19

Warning letters were also sent to 12 online retailers targeting youth with e-liquids labeled in a misleading manner and/or advertised as kid-friendly food products such as candy and cookies.

The evidence is still mixed about the safety of e-cigarettes and its efficacy as a smoking cessation tool. A cross-population study of 5,863 adults who had smoked in the past 12 months and tried to quit at least once with an e-cigarette, over-the-counter NRT or no aid at all, found those who used e-cigarettes were 63 percent more likely to be successful compared with those using NRT and 61 percent more successful than those trying to quit with no help.20

"If used for smoking cessation, patients should avoid dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes, and the goal should be complete discontinuation of both products," says Pamela B. Morris, MD, FACC, chair of ACC's Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Section.

Because e-cigarettes contain few if any of the 7,000 chemicals found in regular cigarettes, they are generally believed to be safer. While a recent report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) on the public health effects of e-cigarettes identified cellular damage from e-cigarette use, including endothelial cell dysfunction and reactive oxygen species/oxidative stress formation that could lead to tissue damage and disease, the report noted there is no available evidence as to whether e-cigarettes are associated with clinical cardiovascular outcomes or cancer in humans.21

The IOM also concluded, however, there was "substantial evidence" the use of e-cigarettes results in nicotine dependence, although the risk and severity appear lower than for cigarettes.

Nonetheless, e-cigarettes are increasingly being viewed as a harm reduction approach to reduce the use of tobacco products in adults who smoke.7

Practical Tools

Given that smoking is one of the leading preventable causes of cardiovascular disease, it is critical that cardiovascular professionals assess the smoking status of their patients and implement evidence-based interventions to help them quit. This should be considered just as important as prescribing medication for hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

"It's imperative that clinicians assess the use of tobacco products with all patients and support efforts for complete cessation," says Morris. Measuring and tracking is a key step and the PINNACLE Registry helps practices with this for each 'ABCS:' aspirin when appropriate, blood pressure control, cholesterol management and smoking cessation.

"Effective treatment of tobacco dependence is best achieved and managed by a team approach utilizing all members of the cardiovascular care team," adds Morris. The Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Member Section at ACC.org is a community and resource for the entire team for addressing all risk factors.

References

- Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu SS, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:597-603.

- Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:53-9.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1513-9.

- Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Carter BD, et al. Ann Epidemiol 2015;25:179-182.e1.

- Surgeon General Report. The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Available here.

- Rostron BL, Chang CM, Pechacek TF. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1922-8.

- Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1030-45.

- Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD. JAMA 1999;281:1019-21.

- Ekpu VU, Brown AK. Tob Use Insights 2015;8:1-35.

- Lightwood J, Glantz SA. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002020.

- Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;65:1457-64.

- Chehab OM, Dakik HA. Postgrad Med J 2018;94:116-20.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation for Adults and Mature Adolescents. 2004. Available here.

- Suissa K, Lariviere J, Eisenberg MJ, et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10(1). pii:e002458.

- Eisenberg MJ, Grandi SM, Gervais A, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:524-32.

- Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann‐Boyce J, Lancaster T. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(5):CD000165.

- Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:629-33.

- Miech RA, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Patrick ME. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:654-59.

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA launches new, comprehensive campaign to warn kids about the dangers of e-cigarette use as part of agency's Youth Tobacco Prevention Plan, amid evidence of sharply rising use among kids. Available here.

- Brown J, Beard E, Kotz D, Michie S, West R. Addiction 2014;109:1531-40.

- Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Insitute of Medicine 2018. Available here.

- Winickoff JP, Hartman L, Chen ML, et al. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e18-e21.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Cardiovascular Care Team, Dyslipidemia, Prevention, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Hypertension, Smoking, Stress

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Aerosols, Aspirin, Blood Pressure, Bupropion, Cardiovascular Diseases, Cholesterol, Smoking, Coronary Disease, Counseling, Endothelial Cells, Harm Reduction, Health Care Costs, Hyperlipidemias, Hypertension, Marketing, Myocardial Infarction, Neoplasms, Nicotine, Office Visits, Oxidative Stress, Prevalence, Public Health, Reactive Oxygen Species, Registries, Risk Factors, Self-Help Groups, Smoking, Smoking Cessation, Stroke, Tobacco Use, Tobacco, Tobacco Use Cessation, Tobacco, Smokeless, Tobacco Products, United States Food and Drug Administration

< Back to Listings