Psychosocial Care in Cardiovascular Medicine: A Necessary Paradigm Change in Training and Practice

Quick Takes

- Behavioral cardiology awareness and practices lead to better cardiovascular outcomes and improved patient care.

- Training programs should incorporate the importance of psychosocial risk factors and their impacts on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and equip trainees with effective strategies to manage them.

- Multidisciplinary psychosocial care teams can play a central role in managing CVD from a biopsychosocial perspective, with unified goals and complementary teams.

In chronic disease, the impact of mental health is underappreciated by both those caring for the chronic disease and those caring for the mental health disorder.1 Mental health and substance use disorders represent 7.4% of the total burden of disease worldwide, surpassing HIV, tuberculosis, and diabetes mellitus.2 Depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder, among others, have been shown to exacerbate cardiovascular disease (CVD), possibly with additive risk.3 However, the training of cardiologists, vascular specialists, and behavioral health practitioners often fails to emphasize the importance and bidirectionality of psychosocial risk factors and CVD. Additionally, patient care is frequently fragmented and lacks connection between specialists. In the following perspective, the lack of integration and awareness of mental health in the management of CVD is discussed.

Terms such as "behavioral cardiology," "cardiac psychology," and "cardiovascular psychology" are used interchangeably and defined as the study and implementation of psychological and social factors to evaluate and mitigate the risk of cardiovascular (CV) disease.4 Psychosocial risk factors, such as depression, stress, and socioeconomic status,3,5 not only affect outcomes but also affect patient adherence, modifiable risk factors, and quality of life.4,5 For instance, the INTERHEART (A Study of Risk Factors for First Myocardial Infarction in 52 Countries and Over 27,000 Subjects) reported an attributable risk of psychosocial risk factors in the primary prevention of myocardial infarction of 25.2% in older patients (men >55 years of age, women >65 years of age) and of 43.5% in younger patients.6 A more recent metanalysis also revealed that depression or depressive symptoms are associated with a 24% increased risk of all-cause mortality in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD).7 Cardiology fellowship and behavioral practitioners often lack awareness of and exposure to these crucial determinants of health. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach involving behavioral health practitioners and cardiovascular (CV) specialists may lead to improved care delivery for these patients.

Psychosocial risk factors play a significant role in CVD, with increasing attention being given to their impact on PAD, as discussed in detail by Smolderen et al.8 PAD is highly prevalent, affecting 8.5 million patients in the United States, particularly among younger individuals and underrepresented populations. Even with optimal medical therapy, the risk of major adverse CV and limb events remains high, at 5-10% per year.9 There is a pressing need to improve the management of these patients, as a substantial proportion of patients with PAD have risk factors associated with psychosocial care, such as smoking, obesity, mental health conditions (especially among young women), and high opioid use.8

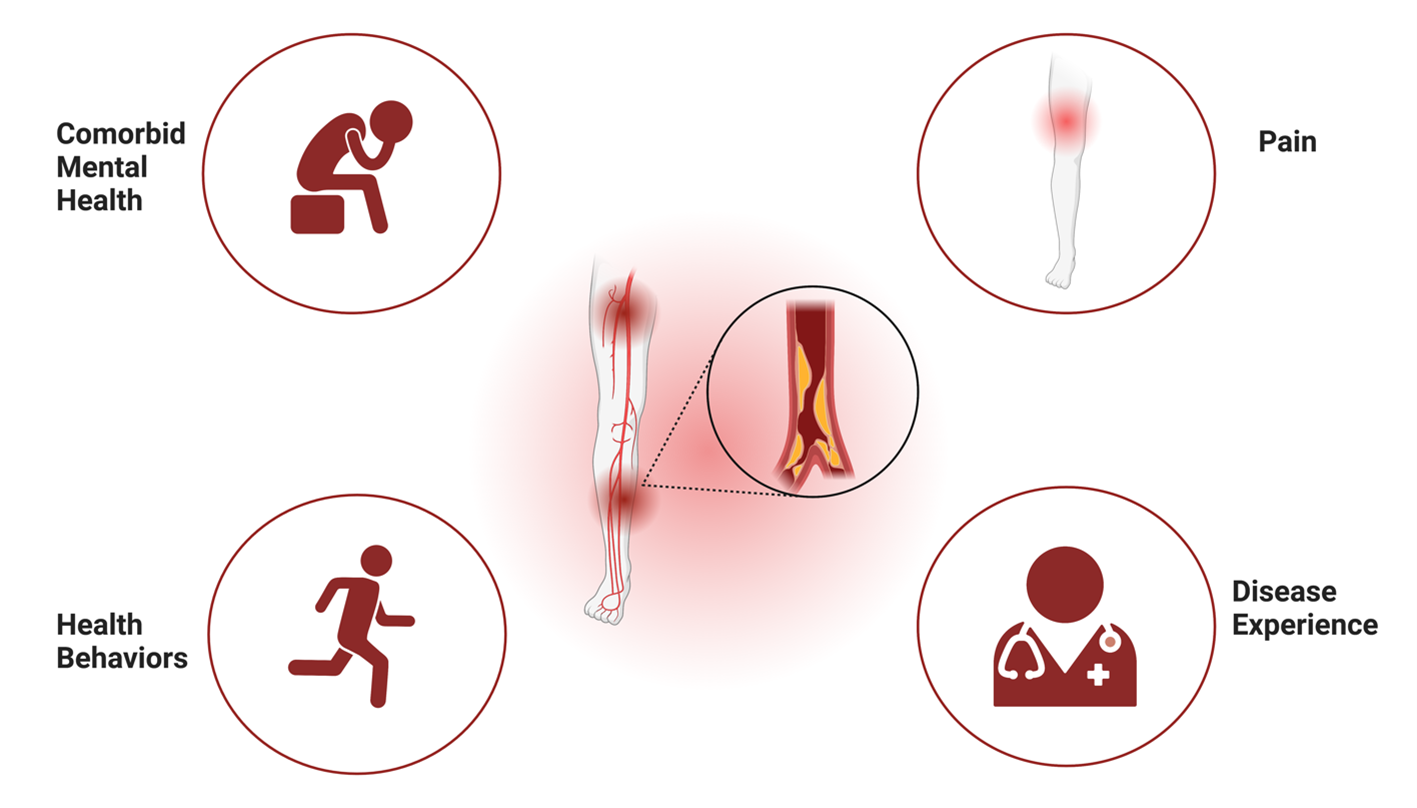

The authors emphasize the importance of the integration of health care systems to address mental health conditions, health behaviors, the multidimensional experience of pain, and the effects of PAD experience as a biopsychosocial phenomenon.8 Although the disease impacts various physical and mental domains, current systems tend to be reactionary and to have isolated goals, limiting the effectiveness of therapies and diminishing quality of life.8 A multidisciplinary integrated team can effectively improve patient care not only in PAD but also in other CVD.

Despite the growing awareness, there is a lack of tools to address psychological comorbidities.10 Advancements in reducing stigma combined with curriculum updates within training programs across specialties could facilitate a more holistic therapeutic approach to care. Codisciplinary training could enable better care from vascular and mental health specialists.

The implementation of psychocardiological care has proven to be effective in a wide array of settings, ranging from outpatient and primary care encounters to screening and short yet impactful interventions in inpatient care.6,8,10 Therefore, behavioral cardiology practices are necessary across the entire spectrum of patient care.

Finally, solutions and adaptations in curricula should receive support from state and national policies.8 The current reimbursement system for health care services has shifted to prioritize stronger financial compensation for procedural and technological care while undervaluing the importance of preventive and psychosocial care.8 Incorporating reimbursement options for behavioral interventions reinforces the significance of addressing psychological risk factors in diverse patient populations. This reimbursement shift will also help raise health administrators' and care teams' awareness of the importance of psychosocial care in cardiology.8

Presently, cardiology fellows receive limited exposure to addressing the multidimensional impacts of the CVD they encounter. Similarly, behavioral practitioners may not be exposed to the nuances of specialized CV assessment and treatment experiences during their training. These nuances shape and interact with the experiences and outcomes of patients undergoing treatment for CVD.8

Multidisciplinary health care teams and training programs integrating specialty care and behavioral health care teams create awareness and will lead to better CV outcomes and patient care (Figure 1).

Figure 1

References

- Goldfarb M, De Hert M, Detraux J, et al. Severe mental illness and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:918-33.

- Sporinova B, Manns B, Tonelli M, et al. Association of mental health disorders with health care utilization and costs among adults with chronic disease. JAMA Netw Open 2019;Aug 2:[ePub ahead of print].

- Kubzansky LD, Huffman JC, Boehm JK, et al. Positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular disease: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1382-96.

- Astin F, Lucock M, Jennings CS. Heart and mind: behavioural cardiology demystified for the clinician. Heart 2019;105:881-8.

- Meng R, Yu C, Liu N, et al.; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Association of depression with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among adults in China. JAMA Netw Open 2020;Feb 5:[ePub ahead of print].

- Albus C, Waller C, Fritzsche K, et al. Significance of psychosocial factors in cardiology: update 2018: position paper of the German Cardiac Society. Clin Res Cardiol 2019;108:1175-96.

- Scierka LE, Mena-Hurtado C, Ahmed ZV, et al. The association of depression with mortality and major adverse limb event outcomes in patients with peripheral artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2023;320:169-77.

- Smolderen KG, Samaan Z, Ward-Zimmerman B, et al. Integrating psychosocial care in the management of patients with vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1201-4.

- Smolderen KG, Alabi O, Collins TC, et al.; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Advancing peripheral artery disease quality of care and outcomes through patient-reported health status assessment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022;146:e286-e297.

- Ludmir J, Small AJ. The challenge of identifying and addressing psychological comorbidities. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1590-3.

Clinical Topics: Vascular Medicine, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Cardiovascular Care Team, Prevention

Keywords: Cardiovascular Diseases, Depression, Quality of Life, Outpatients, Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Social Factors, Inpatients, Risk Factors, Myocardial Infarction, Chronic Disease, Peripheral Arterial Disease, Anxiety

< Back to Listings