Management of Coronary Artery Disease in High-Risk Occupations

Quick Takes

- Cardiovascular events can be associated with sudden incapacitation, which in high-risk occupations, could result in catastrophic consequences for the driver or pilot, passengers, and bystanders.

- Additional study of the impact of cardiovascular screening with aggressive risk factor modification on individuals in high-risk occupations is definitely needed.

- A greater emphasis should be placed on early detection of coronary atherosclerosis in these high-risk populations, rather than focusing on mitigating ischemia once it occurs through interventions that have not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with stable ischemic heart disease without high-risk anatomy.

Introduction

The prevention of and screening for coronary artery disease (CAD) is important for all adults. However, for those working in the transportation industry, the risk of sudden impairment due to a cardiac cause could have catastrophic consequences for many others. A recent review focused on two high-risk occupations, commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers and pilots, and discussed the current regulatory guidelines in the context of up-to-date clinical research.1

The review summarized current United States (US) guidelines, drew comparisons to European guidelines, and challenged some current regulatory agency recommendations. Further, the article provided additional recommendations that could be adopted in future guideline iterations.

CMV Drivers

In the US, CMV drivers must be certified by a medical examiner every 2 years for their license. Screening for CAD is an important aspect of these evaluations, as arrhythmias due to ischemia or myocardial infarction (MI) could result in abrupt driver incapacitation. Traditional risk factors for coronary heart disease include smoking, hyperlipidemia, high body mass index, diabetes, and hypertension, which are prevalent in CMV drivers. Coupled with occupational risks including stressful shift work, air pollution, carbon monoxide and hydrocarbon exposure, and sedentary habits, many CMV drivers have an elevated risk for cardiovascular events.

A medical examination includes a review of prior cardiac symptoms, a review of systems, and a urinalysis. Importantly, medical examiners rely on CMV drivers to self-report cardiac and other symptoms. Applicants for CMV licensure are categorized by the examiner as asymptomatic low risk, asymptomatic high risk, and symptomatic. Asymptomatic low risk individuals are not required to undergo further cardiac evaluation.

Evaluation of asymptomatic high-risk persons is at the discretion of the examiner. Symptomatic patients are always referred for further evaluation, typically to a cardiologist. The review debates this approach, suggesting that regulatory guidelines should emphasize lifestyle modification and medical therapy for risk factor modification rather than only including passive screening for symptomatic coronary heart disease.

Management of Known CAD in CMV Drivers

CMV drivers who have undergone a cardiac evaluation and deemed low enough risk to continue driving with a CMV license may continue driving. Drivers who experience stable angina require an annual CMV medical examiner as well as a cardiologist's evaluation, including periodic stress testing. CMV drivers who experience an MI cannot work until re-evaluation for licensure. Diabetes, lipid, and blood pressure control are goals during the initial and ongoing assessments.

Post-Revascularization Considerations in CMV Drivers

Drivers who undergo revascularization for angina without an MI must be re-evaluated after their procedure. Targeting risk factor control at the initial and annual follow-up medical examinations is important, given that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) does not reduce the future risk of MI or death in stable ischemic heart disease.2,3

Drivers who undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) must wait at least 3 months after their surgery before seeking re-certification, followed by re-evaluation by a certified CMV medical examiner, a cardiologist, and are followed up with periodic stress testing.1

Commercial Pilots

Commercial pilots require medical evaluation and examination to obtain a first-class certificate. Pilots at higher but still acceptable risk of sudden incapacitation may be granted special issuance, be restricted to co-pilot, or be denied certification. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause for pilots to be denied flying privileges.

Pilots are also categorized as asymptomatic low risk, asymptomatic high risk, and symptomatic. The review discusses that if the objective is to definitively rule out obstructive CAD, an anatomy-driven path, in which asymptomatic pilots could undergo screening coronary computed tomography (CT) angiograms at defined ages, would be very useful. This would allow identification of pilots with subclinical CAD and pilots with high-risk anatomy, with the objective of aggressively addressing modifiable risk factors with optimal medical therapy and lifestyle modification in those without high-risk anatomy. Detection of nonobstructive coronary atherosclerosis by coronary CT angiography has been associated with lower risk of MI in patients with stable chest pain, since that often leads to earlier implementation of more aggressive risk factor modification.3

Currently, coronary revascularization of ischemia-causing obstructive CAD is still the only treatment that is deemed sufficient to mitigate a pilot's risk, potentially allowing special issuance (the ability to continue to fly as a pilot, though possibly limited to co-pilot). Cardiologists may be asked to consider performing PCI in a manner that is not consistent with standard clinical practice, including revascularization of asymptomatic CAD with or without proven inducible ischemia.

MI in Pilots

Once a pilot has experienced an MI, they must provide evidence that they have no ischemia, no arrhythmias, have a low residual CAD burden, normal cardiopulmonary function off all anti-anginal medications, and must commit to long-term surveillance for disease progression and adherence to secondary prevention goals.

Post-revascularization Considerations for Pilots

Pilots who undergo PCI of vessels other than the left main coronary artery are required to recover for at least 3 months, followed by re-evaluation with stress testing, a medical examination by an aviation medical examiner, and a cardiologist. Pilots who undergo CABG or left main PCI are required to recover for at least 6 months before re-applying for a Class I license.

Similar to patients who undergo non-left main PCI, these patients must undergo re-evaluation by an aviation medical examiner and a cardiologist and demonstrate no residual ischemia or symptoms prior to resuming flying. The review recommends that greater emphasis should be placed on mitigation of risk of future cardiovascular events through aggressive modifiable risk factor modification and screening for progression in CAD with anatomic evaluation, rather than functional testing.

Conclusions

Cardiovascular events can be associated with sudden incapacitation, which in high-risk occupations, could result in catastrophic consequences for the driver or pilot, passengers, and bystanders. Additional study of the impact of cardiovascular screening with aggressive risk factor modification on individuals in high-risk occupations is definitely needed. There is also a great need for increased regulatory agency transparency to allow for a better understanding of how screening and treatment recommendations impact a given patient's ability to gain and maintain employment.

The authors strongly argue that greater emphasis should be placed on early detection of coronary atherosclerosis in these high-risk populations, rather than focusing on mitigating ischemia once it occurs through interventions that have not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with stable ischemic heart disease without high-risk anatomy. This review highlights the need for updates to commercial motor vehicle and aviation medical examiner guidelines, urging the regulatory agencies to consider the screening and treatment recommendations in the context of the most up-to-date clinical literature.

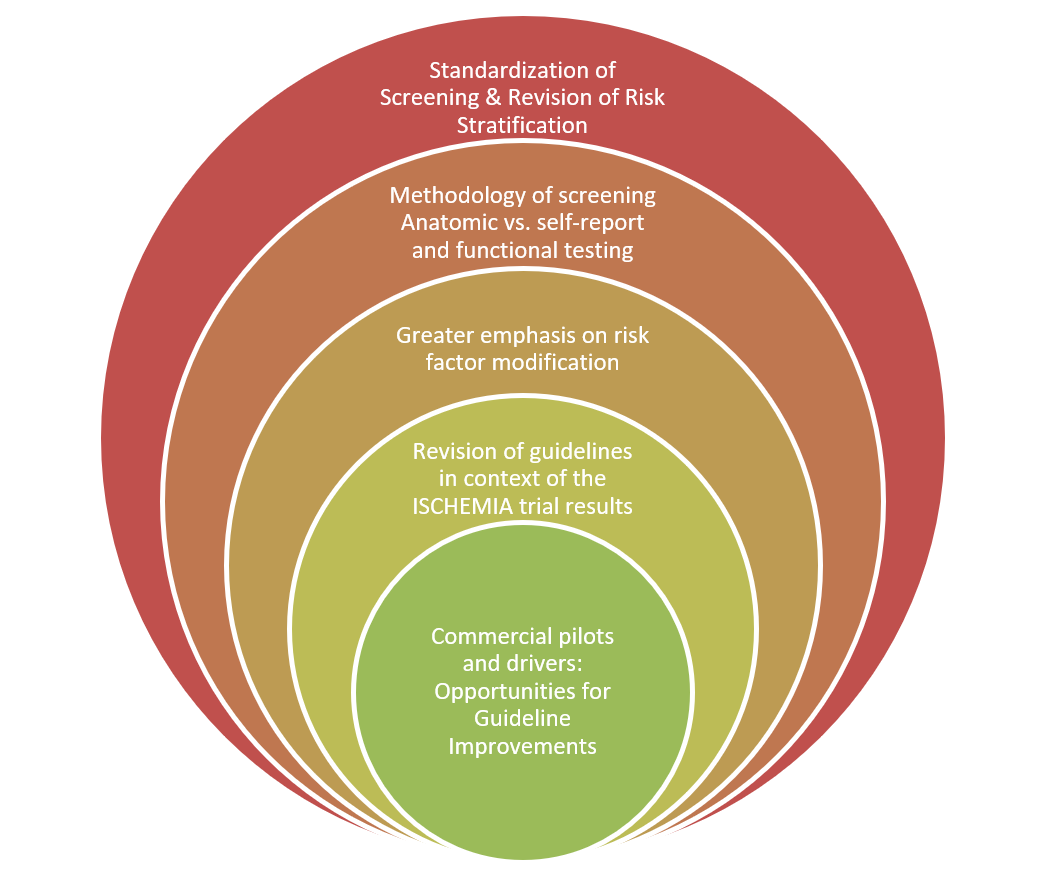

Figure 1

References

- Sutton NR, Banerjee S, Cooper MM, et al. Coronary artery disease evaluation and management considerations for high-risk occupations: commercial vehicle drivers and pilots. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:e009950.

- Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. New Engl J Med 2020;382:1395-1407.

- Ferraro R, Latina JM, Alfaddagh A, et al. Evaluation and management of patients with stable angina: beyond the ischemia paradigm: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2252-66.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Prevention, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and SIHD, Lipid Metabolism, Interventions and Coronary Artery Disease, Hypertension, Chronic Angina, Vascular Medicine

Keywords: Dyslipidemias, Coronary Artery Disease, Coroners and Medical Examiners, Angina, Stable, Cardiovascular Diseases, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Blood Pressure, Secondary Prevention, Body Mass Index, Hyperlipidemias, Follow-Up Studies, Coronary Artery Bypass, Hypertension, Myocardial Infarction, Risk Factors, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Diabetes Mellitus, Life Style, Occupations, Ischemia, Lipids, Disease Progression, Employment, Hydrocarbons, Aviation, Cytomegalovirus Infections, Motor Vehicles, Reference Standards, Automobile Driving, Primary Prevention

< Back to Listings