Feature Story | Palliative Care in Heart Failure

Despite evidence showing improved quality of life (QOL), palliative care is often overlooked in the treatment and care of patients with heart failure (HF). Unlike in oncology, there is a lag in research, as well as limited training for cardiovascular professionals when it comes to palliative care in HF.

While the focus of clinicians may tend towards drugs and devices, palliative care is complementary and addresses concerns of patients, families and caregivers about QOL and eventually end of life care. Notably, however, often these concerns are not voiced, because cardiovascular professionals don’t start the conversation. Read More >>>

The first randomized trial in HF of palliative care, PAL-HF, found that an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention in addition to usual care in patients with advanced HF improved QOL, anxiety, depression and spiritual well-being compared with usual care alone.1 Hospitalizations and mortality were not changed in PAL-HF. The interdisciplinary approach involved a nurse practitioner collaborating with a palliative medicine physician and hospice, in coordination with the clinical cardiology team. The nurse practitioner contacted patients in the intervention group every three months to provide ongoing support and clinical care.

The more recent SWAP-HF pilot randomized trial showed that a palliative care intervention led by a specially trained social worker resulted in a greater likelihood of physician-level documentation of care preferences in the electronic health record.2 Furthermore, patients’ estimation of life expectancy was better aligned with that of their physician, without worsening scores for depression, anxiety or QOL.

"The recent death of Barbara Bush, who suffered for many years with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is a reminder of the importance of caring for the complete patient, and understanding patient and family needs, as well as quality of life as a priority over quantity of life." — Christopher M. O’Connor, MD, MACC

An analysis by Dio Kavalieratos, PhD, et al., in a topic review found “there is generally consistent evidence that a palliative approach improves a variety of patient-centered outcomes, including symptom burden and QOL.” Stating the evidence base for palliative care in HF is nascent, they identified six palliative care intervention trials that met their inclusion criteria.3

The recent death of Barbara Bush, who suffered for many years with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is a reminder of “the importance of caring for the complete patient, and understanding patient and family needs, as well as quality of life as a priority over quantity of life,” says Christopher M. O’Connor, MD, MACC, in a new Editor’s Page in JACC: Heart Failure.4

Goals of care discussions and shared decision-making are key components of optimizing care for patients with heart failure. And aids with determining the transition from palliative to hospice care.

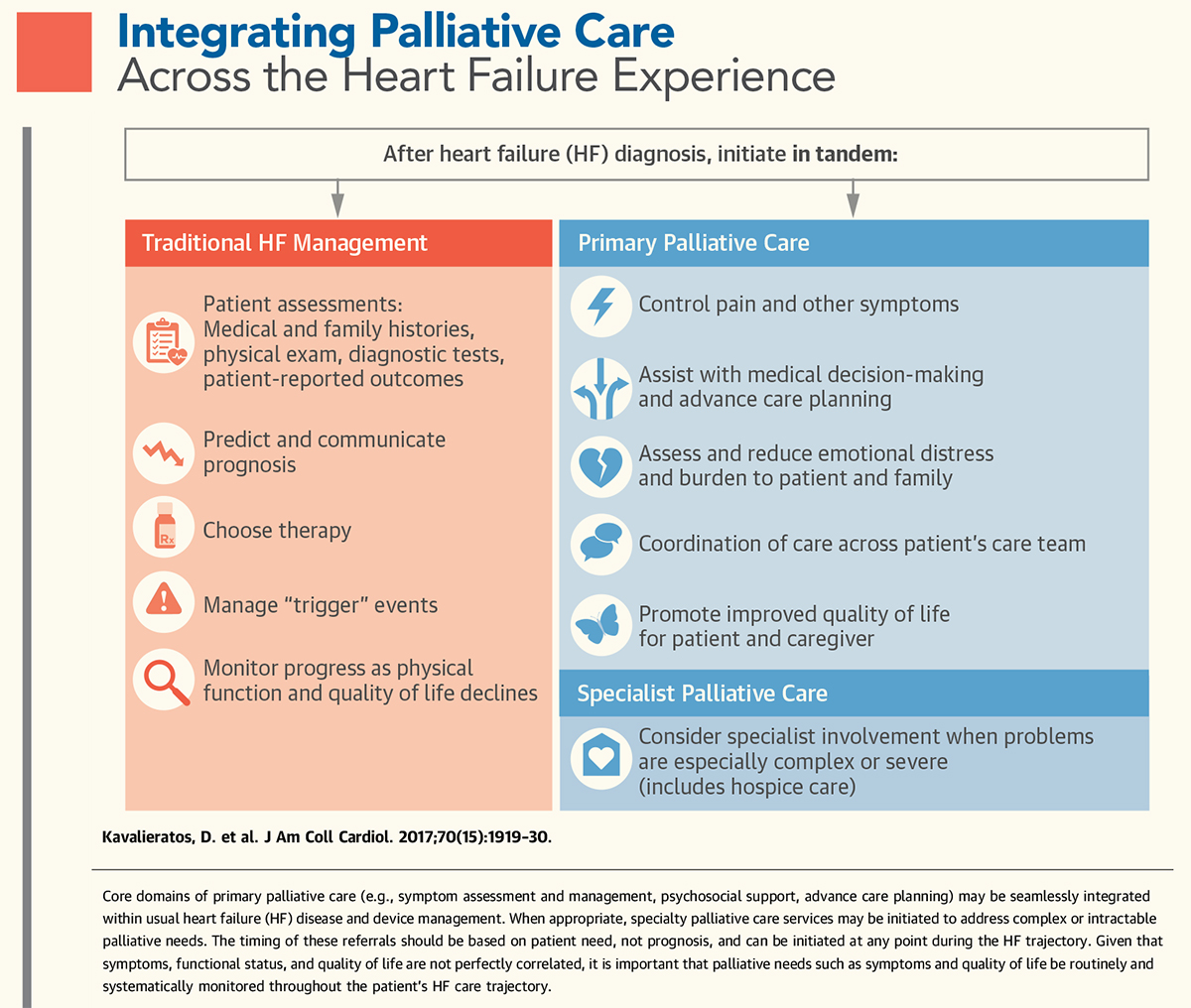

The seamless integration of palliative care principles throughout the heart failure management continuum is recommended — and should start early. Kavalieratos and colleagues point out this process should begin with the diagnosis of heart failure. Each hospital admission as well as instituting advanced therapies such as ventricular assist devices and cardiac transplantation represent natural trigger points to re-evaluate (or establish) goals of care and expand the conversation with the patient.

“Hospital discharge planning is an opportunity to discuss what is most important, what QOL means to the patient and family, and under what circumstances they would and would not want life-prolonging treatments,” they write. Regarding advanced therapies, the discussion with the patient should include palliative care and device deactivation during end of life care, and involving specialty palliative care is recommended by many guidelines.

Primary palliative care is mostly provided by the provider of the patient’s ongoing care, i.e., the cardiovascular professional and/or the primary care physician. The Cardiovascular Team is an invaluable asset and crucial for coordination of postdischarge care and ongoing support for patient, family and caregiver.

What are the tools to help you integrate palliative care into your practice? ACC’s tools and resources are highlighted below.

References

- Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:331-41.

- O’Donnell AE, Schaefer KG, Stevenson LW, et al. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:516-9.

- Kavalieratos D, Gelfman L, Tycon LE, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1919-30.O’Connor CM. JACC: Heart Fail 2018;6:536-7.

Principles to Guide Palliative Care, Transition to Hospice

The 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment, which focused on HF with reduced ejection fraction, provides seven principles and a corresponding action to guide palliative care and the transition to hospice.

Principle 1: Palliative care strives to reduce suffering through the relief of pain and other distressing symptoms while integrating psychological and spiritual aspects of care.

Action: Soliciting goals of care and focusing on quality of life are appropriate throughout the clinical course of heart failure (HF), and become increasingly important as disease progresses. Read More >>>

Principle 2: Good HF management is the cornerstone of symptom palliation.

Action: Meticulous management of HF therapies — particularly diuretics — is a critical component of symptom management and should continue through end of life.

Principle 3: Palliative care consultation and complementary approaches to care may further ameliorate refractory HF symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, and pain, although study results have been mixed.

Action: Targeted specialty palliative care consultation can be helpful for especially complex decisions, refractory symptoms, and end of life.

Principle 4: Patients with HF often face major treatment decisions over time and should be provided with support when thinking through the benefits and burdens of each treatment option.

Action: Decision support tools (patient decision aids) help frame options, which should then be followed by dynamic and personalized conversations.

Principle 5: Proactive shared decision-making discussions simplify difficult decisions in the future.

Action: Preparedness planning discussions should occur at least annually between patients and clinicians leading to review of clinical status and current therapies, estimates of prognosis, clarification of patient values and beliefs, anticipation of treatment decisions, and advanced care directives that identify surrogate decision-makers (healthcare proxies). Resources to assist patients in these difficult discussions may be useful. Similar preparedness-planning discussions should occur at the time of major procedural interventions (e.g., left ventricular assist device implantation, heart transplantation).

Principle 6: Attention to clinical trajectory is required to calibrate expectations and guide timely decisions, but prognostic uncertainty is inevitable and should be included in discussions with patients and caregivers.

Action: Worsening disease and “milestone events” (e.g., recurrent hospitalization or progressive intolerance of medications due to hypotension and kidney dysfunction) should trigger heightened preparation with patients and families, but without specific estimates of how much time remains due to high levels of unpredictability in the clinical course of HF.

Principle 7: The transition from “do everything” to “comfort only/hospice” is often bridged through a phase of “quality survival,” during which time patients increasingly weigh the benefits, risks, and burdens of initiating or continuing life-sustaining treatments.

Action: Revising the medical regimen for symptom relief and quality of life may involve discontinuation of some recommended therapies (e.g., reducing neurohormonal antagonists in the setting of symptomatic hypotension, deactivation of defibrillator therapy) and the addition of therapies not usually recommended (e.g., opioids for refractory dyspnea).

CardioSmart Resources for Patients and Physicians

Visit CardioSmart.org for a range of tools, decision aids and infographics to help your patient understand their condition and palliative care, and to guide discussions with the patient, family and caregivers.

Click here for “Planning Your Care,” a list of open-ended questions to help patients define goals of care and a list of resources to assist the process.

Don’t miss the infographic on shared decision-making and on heart failure. Look for the four-page decision aid to help patients understand their options for drugs to inhibit the renin-angiotensin system.

ACC’s Advance Care Planning Toolkit

This quality improvement toolkit is designed to equip providers to understand, integrate and document advanced care planning (ACP) into their routine practice. Available online, 15 ACP success metrics and the strategies gathered to support clinicians’ efforts are provided for self-paced learning. Click here to learn more (login required).

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Acute Heart Failure, Heart Transplant, Mechanical Circulatory Support

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Advance Care Planning, Advance Directives, Analgesics, Opioid, Anxiety, Caregivers, Consensus, Decision Making, Decision Support Techniques, Defibrillators, Depression, Diuretics, Documentation, Dyspnea, Electronic Health Records, Heart Failure, Heart Transplantation, Heart-Assist Devices, Hospice Care, Hospices, Hypotension, Life Expectancy, Life Support Care, Nurse Practitioners, Pain, Palliative Care, Palliative Care, Patient Care Planning, Patient Discharge, Patient Transfer, Physicians, Primary Care, Prognosis, Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive, Quality Improvement, Quality of Life, Referral and Consultation, Renin-Angiotensin System, Social Work, Stroke Volume, Terminal Care, Trigger Points

< Back to Listings