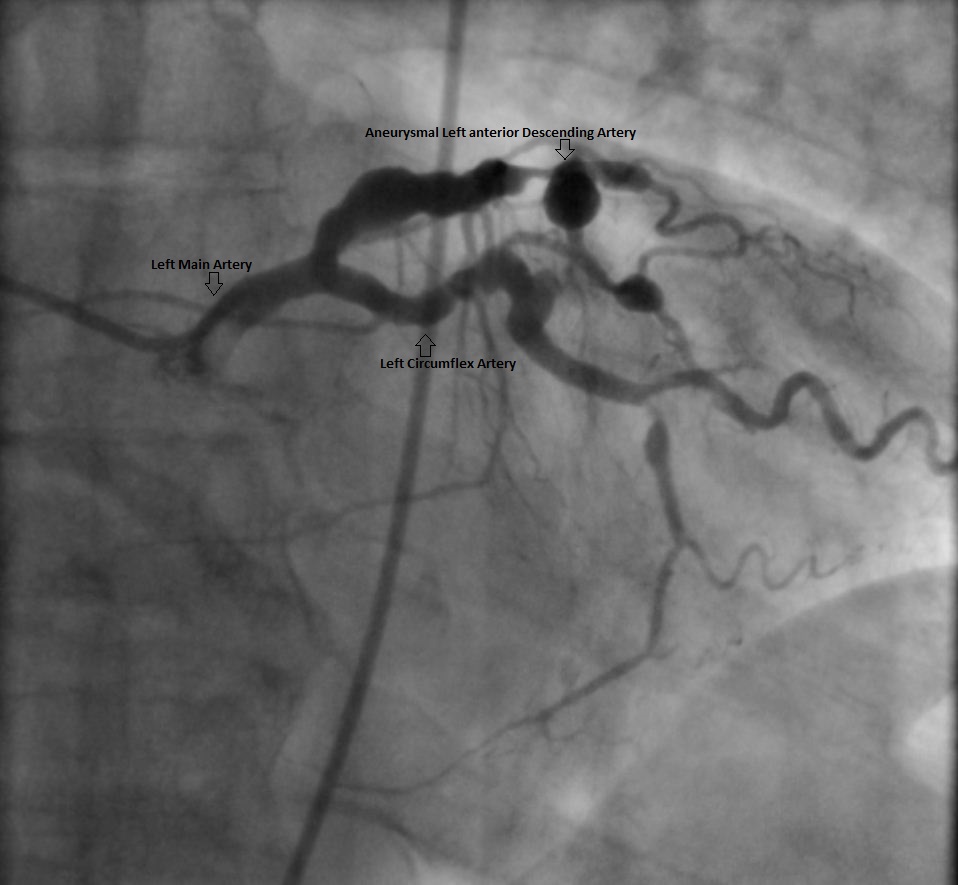

A 68-year-old man with previous history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia develops a sinus tachycardia after hip replacement. A computed tomography (CT) scan excludes pulmonary embolism; however, an incidental mass is detected near his right atrium. A testing cascade is launched, and echocardiography shows normal left ventricular size and function; however, the right atrium is small and is being compressed by an external mass. This is followed by a cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) scan, which identifies a 3.4 x 3.1 cm (diameter) x 5.5 cm (length) aneurysm of the proximal right coronary artery (RCA) (Figure 1). The distal vessel is partially visualized with some smaller aneurysms. The remainder of the study is unremarkable. As his management options are being considered, catheterization is recommended to evaluate his right heart pressures and left coronary system. The right heart pressures and cardiac output are normal without evidence of left to right shunting. His right coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) is of the same dimension as previously seen on CMR. His physicians hope to advance the angioplasty wire to the distal RCA and advance a small catheter to this segment to inject contrast, but are unable to do so. Of note, the injected contrast remains accumulated into the aneurysm for several minutes (Figure 2). The left main coronary is normal, however; there is ectasia in the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) followed by 70-80% stenosis in the mid LAD that ended in a large aneurysm at a bifurcation of a diagonal branch. This aneurysm is around 1.0 cm in diameter (Figure 3). The circumflex also has proximal ectasia but no angiographic evidence of significant stenosis.

The correct answer is: C. Surgical intervention.

A CAA is defined as a dilation of the coronary arteries with a diameter of 1.5 times or greater than that of the adjacent normal coronary vessel.1-4 These aneurysms can vary in size from a few millimeters to greater than 50 mm. Although small CAAs are occasionally encountered during coronary angiography, aneurysms greater than 50 mm are quite rare with an estimated prevalence of around 0.02%.5

Most coronary aneurysms are asymptomatic; however, they may present with angina, myocardial infarction, or sudden death. Complications such as acute rupture into a cardiac chamber or pericardium may occur.1,2,6 Coronary-cameral fistulae have also been reported rarely.5 Other complications include thromboembolic phenomena and compression of surrounding structures.1

CAA may be detected by noninvasive tools like echocardiography, CT angiography, and CMR imaging.2,3,7 However, coronary angiography can still provide valuable information about size, shape, location, and coexisting abnormalities, such as narrowing of the coronary arteries.2

The most common cause of CAA is atherosclerosis. However, connective tissue disorders (like Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome), autoimmune disorders (like Kawasaki disease),6 Systemic lupus erythematosus, Polyarteritis nodosa, Takayasu's arteritis), iatrogenic causes (after percutanuous coronary intervention2), congenital malformation and inflammation due to infections (like syphilis, septic emboli) can also lead to CAA.2,3 Blunt chest trauma, idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, and coronary artery angiodysplasia can also contribute to CAA. A literature review shows that the incidence of coronary aneurysm is highest in the RCA, followed by the LAD and left circumflex arteries.8

Clinical presentation, course, prognosis, and management of CAA are not well defined due to limited experience.1,2 CAAs that are small and thick-walled have a relatively low risk of rupture. They are usually not associated with myocardial ischemia and can be observed without surgical intervention. Giant CAAs (CAA with a diameter more than 20 mm), on the other hand, have a tendency for complications, including rupture, and may present as a mediastinal or intracardiac mass.2 There are reports of superior vena cava syndrome, as well.1,2 Ischemic symptoms may be related to the accompanying narrowing in atherosclerotic aneurysms or from thromboembolism. The major factors playing a role in thrombus formation are platelet (especially in Kawasaki disease) as well as endothelial activation due to flow disturbance from stagnation of blood and turbulence, creating a milieu for thrombus formation. Therefore, low-dose aspirin can be used in patients with mild, stable disease. In other cases, a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel is found to be more effective in preventing vascular events.9 For CAAs that get thrombosed or calcified without evidence of ischemia on noninvasive testing, medical therapy alone may be needed, such as in in cases with mild, stable disease. However, there have been no randomized trials and most of the recommendations are based on short case series, retrospective studies, or anecdotal evidence, primarily in aneurysms associated with KD. In patients with concomitant atherosclerotic narrowing or in those who develop thrombus with distal embolization leading to myocardial ischemia or infarction, treatment as well as prognosis is the same as for patients with atherosclerosis with ischemia or infarction.10,11

The literature suggests that surgery is the preferred approach for giant CAA. Proximal and/or distal ligation, resection with end-to-end anastomosis, or the use of an interposition vein graft have all been used, usually in conjunction with coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).2 However, a combination of low-dose aspirin with warfarin (internationalized normalized ration [INR] goal of 2.0 to 2.5) has also been used in giant aneurysms to prevent thrombosis.9

In this case, the patient is referred for cardiothoracic surgery after all of the above-mentioned options were presented. The patient undergoes CABG with a left internal mammary artery graft to the LAD, and separate saphenous vein grafts to the obtuse marginal and the distal RCA, along with RCA aneurysmectomy. At one month after the surgery, the patient is doing quite well and is able to carry on with activities of daily living.

References

- Banerjee P, Houghton T, Walters M, Kaye GC. Giant right coronary artery aneurysm presenting as a mediastinal mass. Heart 2004;90:e50.

- Jha NK, Ouda HZ, Khan JA, Eising GP, Augustin N. Giant right coronary artery aneurysm- case report and literature review. J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;4:18.

- Rios Gomez E, Martin M, Lozano I, Luyando LH. A giant right coronary artery aneurysm as an incidental finding. Eur J Echocardiogr 2011;12:371.

- Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation 1983;67:134-8.

- Ipek G, Omeroglu SN, Goksedef D, Balkanay OO, Basar I, Ayan F. Giant right coronary artery aneurysm associated with coronary-cameral fistula. Texas Heart Inst J 2012;39:442-3.

- Marcy PY, Civaia F, Poudenx M, Thariat J, Dor V. An 11-cm right coronary aneurysm causing heart compression. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:e99.

- Alomar-Melero E, Martin TD, Janelle GM, Peng YG. An unusual giant right coronary artery aneurysm resembles an intracardiac mass. Anesth Analg 2008;107:1161-2.

- Ozaydin M, Gedikli O, Dogan A, Altinbas A, Varol E. Right coronary artery aneurysm mimicking aortic root dissection. Texas Heart Inst J 2004;31:196-7.

- Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation 2004;110:2747-71.

- Crawley PD, Mahlow WJ, Huntsinger DR, Afiniwala S, Wortham DC. Giant coronary artery aneurysms: review and update. Texas Heart Inst J 2014;41:603-8.

- Mavrogeni S. Coronary artery ectasia: from diagnosis to treatment. Hellenic J Cardiol 2010;51:158-63.