An 11-year-old male presents to the office for an evaluation regarding recurrent pericarditis. He has left-sided chest pain, pleuritic, relieved on bending forward, worsened on laying down, and irradiates to both shoulders. He denies shortness of breath on exertion, orthopnea, significant weight gain, leg swelling or history of syncope.

In the last four years, he has had approximately 25 flares of chest pain. He reports two different types of chest pain: sharp, stabbing pain when he suspects there is no fluid around his heart and a "foggy, hard to breathe" feeling when he suspects there is fluid around his heart. His mother reports five to seven emergency department visits for chest pain, two of which included overnight admissions. His autoimmune serology workup was negative, including antinuclear and smooth muscle antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). He has been treated initially with ibuprofen and colchicine, then prednisone and canakinumab were added because of inadequate response to ibuprofen. His family history is relevant for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in his paternal aunt and rheumatoid arthritis in his paternal great uncle.

At the office, his blood pressure was 113/69 mmHg, his pulse was 70 beats per minute, and his oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On exam, his lungs were clear, and he had irregular S1 and S2 with no murmurs or pericardial knock, no jugular venous distention, no Kussmaul's sign, and no peripheral edema.

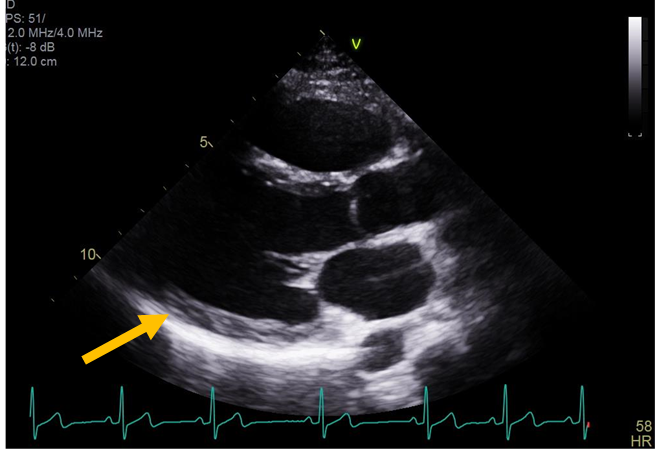

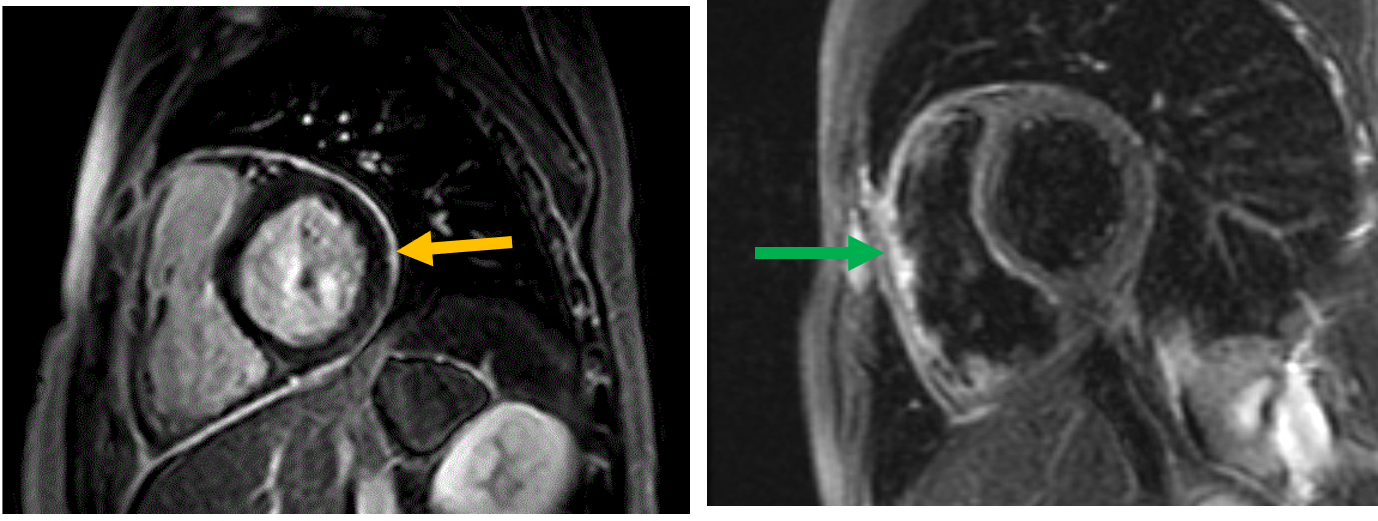

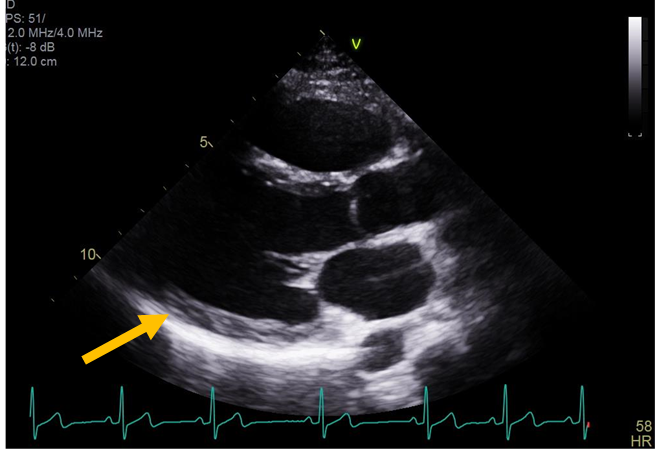

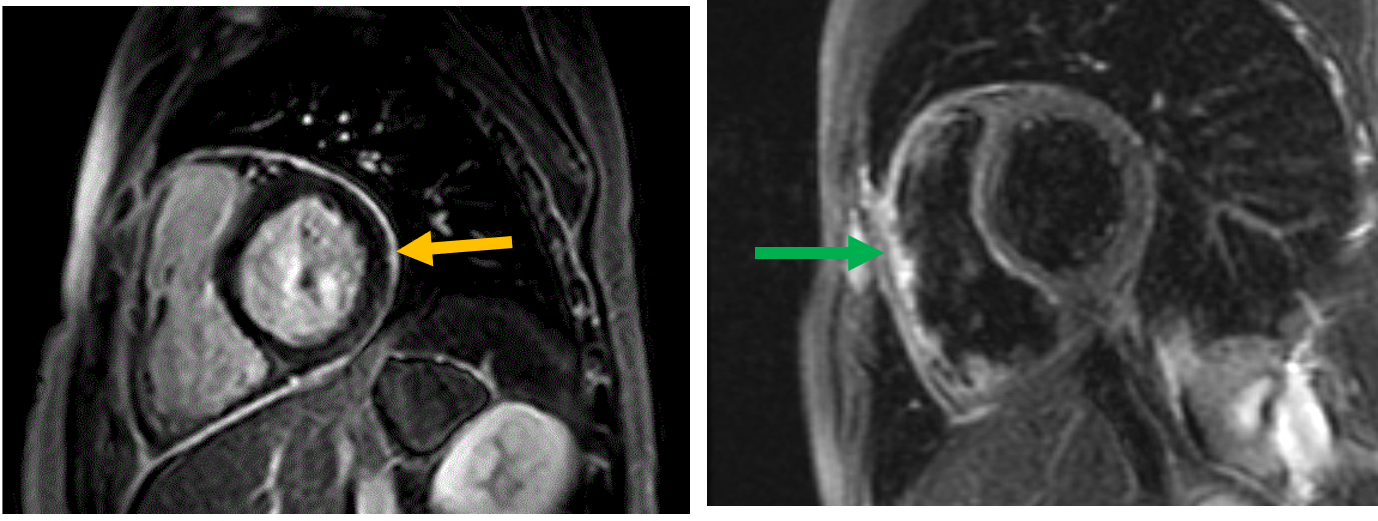

His ultrasensitive C-reactive protein was 0.5 mg/deciliter (normal less than 3.1 mg/dL), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 2 mm/hour (normal less than 15 mm/hour). Electrocardiogram showed sinus arrhythmia. Transthoracic echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 62% without any pericardial effusion or constriction (Figure 1). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed diffuse pericardial delayed enhancement, most prominent inferiorly and posteriorly, along with increased pericardial signal intensity on T2 short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) imaging (Figure 2). There was no pericardial effusion, pericardial thickening, or features of concomitant constrictive pericarditis.

Figure 1

Figure 1: Echocardiogram parasternal long axis view shows no pericardial effusion (orange arrow).

Figure 1: Echocardiogram parasternal long axis view shows no pericardial effusion (orange arrow).

Figure 1: Echocardiogram parasternal long axis view shows no pericardial effusion (orange arrow).

Figure 2

Figure 2: Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing delayed enhancement of the pericardium (orange arrow) and pericardial edema on T2 short-tau inversion recovery (green arrow).

Figure 2: Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing delayed enhancement of the pericardium (orange arrow) and pericardial edema on T2 short-tau inversion recovery (green arrow).

Figure 2: Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing delayed enhancement of the pericardium (orange arrow) and pericardial edema on T2 short-tau inversion recovery (green arrow).

He was switched to anakinra (since canakinumab was deemed ineffective), colchicine, prednisone and meloxicam. He had a right forearm biopsy of a skin nodule which showed histologic features of middle vessel vasculitis suggestive of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa.

Despite quadruple anti-inflammatory therapy, his pericarditis symptoms remained very debilitating; he is now unable to play baseball and has difficulty ambulating around the house. The decision was made to undergo a radical pericardiectomy. Pathology of the excised pericardium exhibited diffuse fibrous adhesions with minimal chronic inflammation. After the surgery, his chest pain resolved; however, he continued to have left-sided abdominal pain, diarrhea, and elevated liver enzymes. Magnetic resonance enterography showed wall thickening and mucosal enhancement of the rectum and sigmoid colon that may be secondary to inflammatory colitis.

The correct answer is: A. Pericarditis is more commonly seen in middle and small-vessel vasculitis than in large-vessel vasculitis.

The etiology of pericarditis can be very diverse: idiopathic, viral, autoimmune or autoinflammatory, postoperative or postprocedural, post-myocardial infarction, radiation-induced, and others. The incidence of systemic diseases as the etiology of acute pericarditis is estimated to be around 3-4%.1,2 Those include connective tissue diseases (like rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, Sjogren's syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease, myositis and rheumatoid arthritis), sarcoidosis, autoinflammatory diseases (like familial Mediterranean fever and tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS)) and vasculitides.3 Regarding vasculitis as the etiology of pericarditis, scarce data are available in the literature. The limited studies available show that medium and small-vessel vasculitis, like Kawasaki and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, more commonly affect the pericardium than large-vessel vasculitis like giant cell and Takayasu arteritis.4-10 In our patient, although, pericardial biopsy did not show early onset of pericarditis, and pathologic evidence of cutaneous medium vessel vasculitis suggest a possible relationship between the two entities.

Pericardiectomy is always used as a last resort after all medical treatment, including biologics, have been tried and failed in patients with debilitating symptoms. The outcomes of pericardiectomy for recurrent pericarditis are still uncertain. It has been reported that pericardiectomy decreased recurrences compared to medical treatment alone; however, other studies indicate persistence of chest pain after the surgery that was postulated to be due to inflammation of a remnant of the pericardium below the phrenic nerve or inflammation of the parietal pleura now covering the pericardium.11,12 Pericardiectomy should only be done in centers with high expertise who are familiar with the procedure and its complications,13 preferably after minimizing active inflammation medically prior to the surgery.

In children, like in adults, prednisone is generally not a first-line treatment for acute pericarditis and should be even more restricted than in adults because of its significant side effect on development and growth.13

The 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases define a recurrent pericarditis episode the same way a first-time acute pericarditis episode is diagnosed, based on the fulfillment of two of the following: typical chest pain, presence of pericardial rub, diffuse ST elevation and PR depression on electrocardiogram, and new or worsening pericardial effusion. There should be around 6 weeks of the absence of symptoms to quality as a recurrent episode.13 Elevated inflammatory markers are considered a supporting finding, and normal markers would not completely rule out a recurrent flare. However, Kumar et al. showed that quantitative measurement of delayed enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is a valuable tool to diagnose pericarditis in the setting of typical chest pain and elevated markers, even if the criteria above are not fulfilled.14

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors are emerging to be a cornerstone in the treatment of steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory recurrent pericarditis. Anakinra is an antagonist of the IL-1 receptor, canakinumab binds to IL-1 beta (not the receptor), and rilonacept binds to IL-1 beta and IL-1 alpha and is an antagonist of the IL-1 receptor.15-17

References

- Gouriet F, Levy PY, Casalta JP, et al. Etiology of pericarditis in a prospective cohort of 1162 cases. Am J Med 2015;128:784.e1-8.

- Zayas R, Anguia M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:378–82.

- Generali E, Folci M, Selmi C, Riboldi P. Immune-mediated heart disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017;1003:145–71.

- Li JJ, Fang CH, Chen MZ, Chen X. Takayasu's arteritis accompanied with pericarditis: a case report. Cardiology 2004;102:106–7.

- Guillaume MP, Vachiery F, Cogan E. Pericarditis: An unusual manifestation of giant cell arteritis. Am J Med 1991;91:662–64.

- Blot M, Guépet H, Aubriot-Lorton MH, Pfitzenmeyer P, Manckoundia P. An atypical case of giant cell arteritis (Horton's disease) associated with facial swelling, confusion, and pericarditis in an elderly woman. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:2040–41.

- Agard C, Rendu E, Leguern V, et al. Churg-Strauss syndrome revealed by granulomatous acute pericarditis: two case reports and a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007;36:386–91.

- Korantzopoulos P, Papaioannides D, Siogas K. The heart in Wegener's granulomatosis. Cardiology 2004;102:7–10.

- Baldini C, Talarico R, Della Rossa A, Bombardieri S. Clinical manifestations and treatment of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2010;36:527–43.

- Cullen S, Duff DF, Denham B, Ward OC. Cardiovascular manifestations in kawasaki disease. Ir J Med Sci 1989;158:253–56.

- Khandaker MH, Schaff HV, Greason KL, et al. Pericardiectomy vs medical management in patients with relapsing pericarditis. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:1062-70.

- Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of acute andrecurrent pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:76-92.

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2921–64.

- Kumar A, Sato K, Verma BR, et al. Quantitative assessment of pericardial delayed hyperenhancement helps identify patients with ongoing recurrences of pericarditis. Open Heart 2018;5:e000944.

- Klein A, Lin D, Cremer P, et al. Rilonacept in recurrent pericarditis: first efficacy and safety data from an ongoing phase 2 pilot clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1261.

- Emmi G, Urban ML, Imazio M, et al. Use of interleukin-1 blockers in pericardial and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Cardiol Rep 2018;20:61.

- Kougkas N, Fanouriakis A, Papalopoulos I. et al. Canakinumab for recurrent rheumatic disease associated-pericarditis: a case series with long-term follow-up. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:1494–95.