A 54-year-old woman with a past medical history of metastatic melanoma who started on immunotherapy 2 months prior presented with 3 weeks of shortness of breath.

At baseline, she had an excellent exercise tolerance. She initially presented to an outside hospital in August of 2017 with several months of non-productive cough, hoarseness, and drenching nightsweats. Computed tomography (CT) scan at that time revealed a 9.6 x 11.8 x 10.7 cm mass in the upper left chest, as well as hilar adenopathy, precarinal lymphadenopathy, multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules, and a small left-sided pleural effusion. A biopsy was consistent with BRAF wild-type melanoma. The pathology revealed nests of tumor cells elongated bundles, positive for S100, SOX10, TLE1, and PDL1. While awaiting the histology results, she began to experience dyspnea on exertion, limiting her exercise tolerance to less than 1 flight of stairs. Repeat scans showed the upper chest mass had increased to 10 x 14 x 12 cm, and her left pleural effusion had worsened. She received large volume thoracentesis with complete relief of her dyspnea of exertion. A catheter was placed. In early September 2017, she was started on ipilimumab 3 mg/kg and nivolumab 1 mg/kg with plans for infusions every 3 weeks. Radiation oncology was consulted and thought that the mass could not be safely irradiated.

Over the next 2 months, she again experienced worsening dyspnea on exertion. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) in October 2017 revealed a moderate-sized circumferential pericardial effusion without evidence of increased pericardial pressures, an ejection fraction of 70%, normal diastolic function, and a right ventricle that was normal in size and function. In November 2017, she presented to the cardio-oncology clinic at The Hospital of University of Pennsylvania. By that time, she was unable to ambulate across the room without severe shortness of breath. She had associated lower leg swelling up to her mid-thigh, orthopnea causing her to sleep upright in a chair, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. She denied palpitations or chest pain. On further review of systems, she noted ongoing nighttime fevers and sweats, decreased appetite, and fatigue. She denied diarrhea, new rashes, pruritis, or hair or nail changes. In addition to her immunotherapies, she was on oxycodone, acetaminophen, and ondansetron as needed. She had no other pertinent cardiac, surgical, or psychological past medical history. She had no allergies.

In cardiology clinic, her vitals were

- blood pressure of 102/70;

- pulse of 114;

- height of 5 ft and 6.5 in (1.689 m);

- weight of 140 lb (63.5 kg);

- blood oxygen saturation of 94%; and

- body mass index of 22.26 kg/m2.

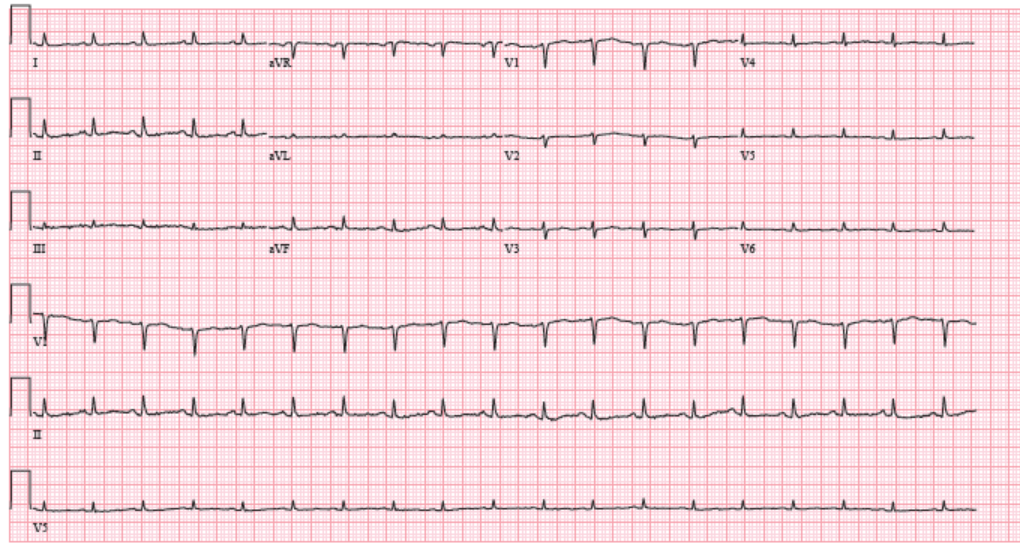

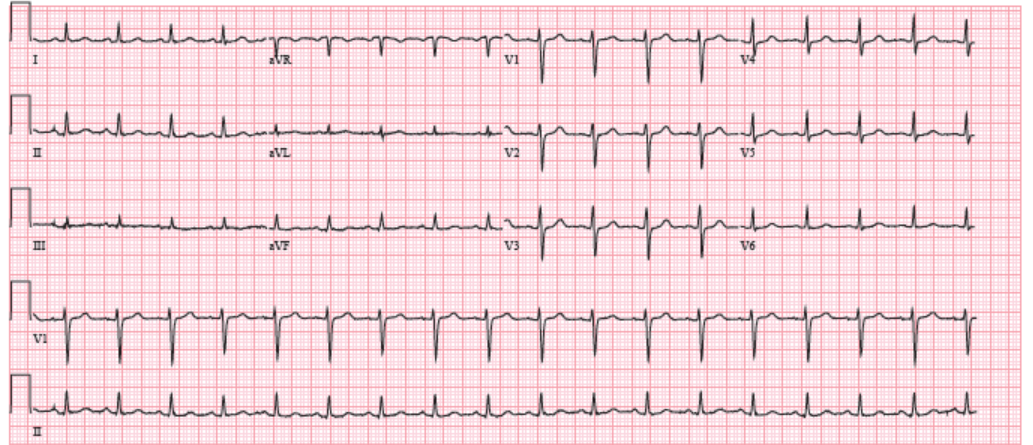

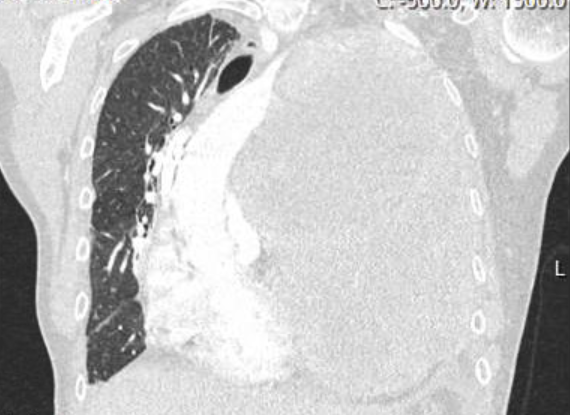

She was thin and uncomfortable but non-toxic appearing. She had a jugular venous pressure of 12 cm without Kussmaul sign and rightward deviation of her trachea. Her cardiac exam revealed a distinct point of maximal impulse in the midclavicular space, an S1 and an S2 but no S3, S4, murmur, or rub. The pulsus was 12 mmHg. Her lungs revealed slightly decreased respiratory sounds at the left base but no rales, rhonchi, or wheezing. She had 3+ pitting edema to the mid-thigh. Labs at that time were notable for normal liver function tests, a normal basic metabolic panel with a creatinine of 0.68, a normal thyroid stimulating hormone and thyroxine level, a normal complete blood count, and a troponin T <0.010. An electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) revealed sinus tachycardia and low voltages that were new compared to prior ECG in August 2017 (Figure 2). A chest CT with intravenous contrast had been ordered by her oncologist 2 days prior to the office visit (Figure 3), which was reviewed. The CT revealed increase in the left upper chest mass to 13 x 17 x 15 cm, with a new area of central necrosis. The pulmonary nodules, lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusion had all improved from prior visits.

Figure 1: ECG at Cardiology Clinic in November 2017

Figure 2: ECG at Office Visit in August 2017

Figure 3: CT Scan With Contrast of the Chest From November 2017

The correct answer is: E. TTE

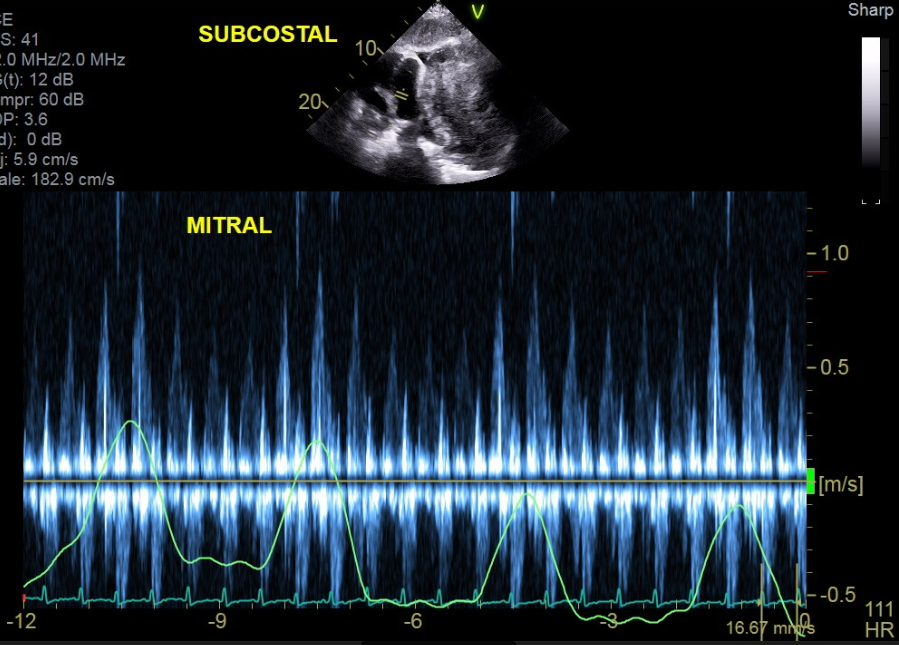

An echocardiogram (answer E) was ordered, which revealed the tumor was compressing the pericardium (Figure 4). The TTE revealed complete right atrial free wall collapse as well as exaggeration of mitral and tricuspid respiratory inflow variance (Figure 5). The moderate circumferential effusion was unchanged in size from prior visits. The patient was experiencing cardiac tamponade from direct compression of the pericardium from the increase in tumor size.

Figure 4: Still Frame of Subcostal 4-Chamber Views

Figure 5: Subcostal View With Pulse Wave Doppler of Mitral Valve Inflow

One possible explanation for the patient's symptoms could be ipilimumab- and/or nivolumab-related cardiotoxicity. Although immunotherapy cardiotoxicity is rare (likely occurring in <1% of patients), there are multiple manifestations of immunotherapy cardiotoxicity, including pericarditis, myopericarditis, myocardial fibrosis, cardiomyopathy, and ventricular tachycardia. Almost all adverse reactions occur within the first year of treatment and usually after the first few infusions. The treatment of choice is high-dose steroids (answer A). The clinician must have a high index of suspicion for these clinical entities, but ultimately they are diagnoses of exclusion. Thus, it is important to rule out other etiologies prior to initiating therapy. Other more common immune-related adverse events to immunotherapies include colitis, hepatitis, thyroiditis, rash, and hypophysitis.

Cardiac MRI (answer B) would have revealed tamponade physiology and may also have shown evidence of immune-mediated cardiotoxicities. That noted, at most institutions it is a less readily available test, and so echocardiography is both more time- and cost-efficient. Lastly, this patient was unable to lie flat for MRI due to her profound orthopnea.

Pericardiocentesis (answer C) is the treatment of choice for hemodynamically significant pericardial effusions. Although this patient had clinical and echocardiographic tamponade, it was caused by extrinsic compression of the pericardium by tumor and not from the pericardial effusion itself. Removing the pericardial fluid would have been unlikely to improve the patient's hemodynamic status. Additionally, most catheterization laboratories require prior echocardiography to assess for subcostal or apical clearance to safely perform the procedure.

Although a watch-and-wait approach (answer D) would not be appropriate for a patient who is increasingly ill, this answer choice allows a discussion of the concept of pseudoprogression. In roughly 10-15% of melanoma patients treated with immunotherapy, there is radiographic progression of the tumor in the first 6 weeks, which is thought to be mediated by necrosis and an influx of inflammatory cells. If imaging within the first 1-2 months on patients treated with immunotherapy reveals tumor enlargement, it becomes clinically challenging to separate pseudoprogression from true treatment failure. Pseudoprogression can also occur in the visceral spaces, and patients with pericardial effusions should be monitored closely for rapid accumulations of pericardial fluid resulting in tamponade.

Given that cardiac tamponade was high on the differential diagnosis, diuresis (answer F) would not be appropriate. Lowering intravascular volume would reduce right atrial filling pressures and could result in hemodynamic collapse.

Repeat CT imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed late November 2017 revealed new bulky lymphadenopathy in the retroperitoneum, groin, and peritoneum; involvement of the lung lymphatic system; increase in the left-sided effusion; and further increase in the left upper chest mass. She was advanced to hospice care and treated with diuretics, benzodiazepenes, opioids, and oxygen. She passed away in December 2017.

References

- Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant Myocarditis with Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1749-55.

- Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2542-52.

- Heinzerling L, Ott PA, Hodi FS, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with CTLA4 and PD1 blocking immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2016;4:50.

- Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, et al. Evaluation of Immune-Related Response Criteria and RECIST v1.1 in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Treated With Pembrolizumab. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1510-7.

- Kolla BC, Patel MR. Recurrent pleural effusions and cardiac tamponade as possible manifestations of pseudoprogression associated with nivolumab therapy- a report of two cases. J Immunother Cancer 2016;4:80.