Redefining Plant-Based Diets For CVD Primary Prevention

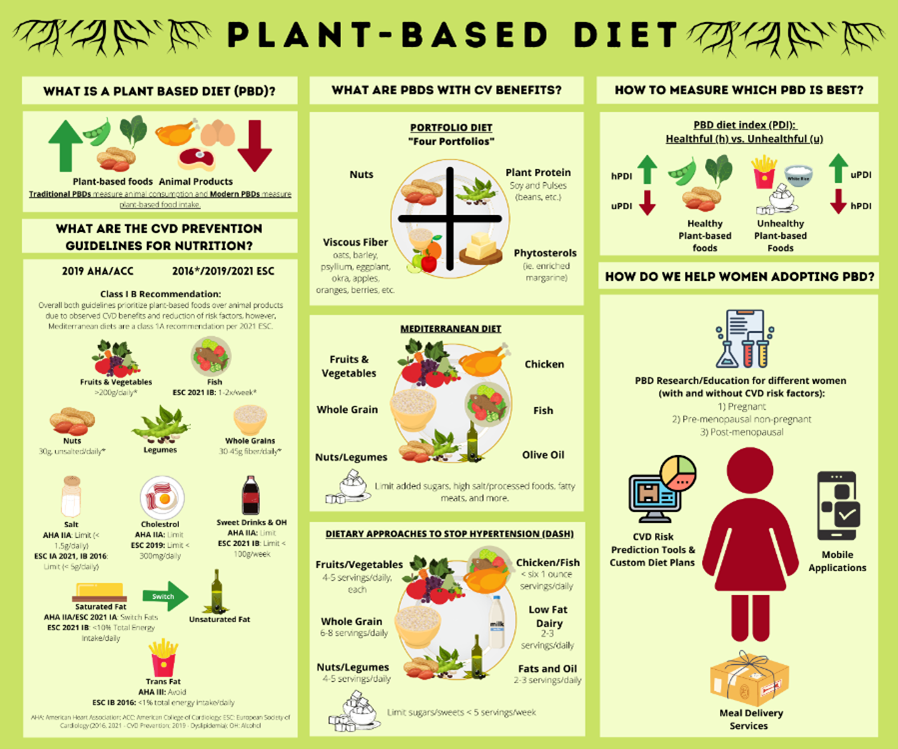

Nutrition is a cornerstone of cardiovascular disease (CVD) primary prevention. Both the 2019 American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) CVD primary prevention guidelines and recently updated 2021 ESC CVD Primary Prevention Guidelines recommend dietary patterns with higher plant-based food intake and lower animal product intake (Figure 1).1-2

Traditional plant-based diets (PBDs) are dietary patterns defined by animal consumption. For example, vegan diets exclude animal consumption while other modified vegetarian diets allow dairy, eggs, fish, and other combinations of animal product consumption.3 In contrast, newer PBDs measure plant-based food consumption rather than animal product limitation, positively reinforcing dietary adherence. For example, the "pro-vegetarian" diet evaluates plant-based foods positively and animal products negatively rather than including or excluding food groups.3

Benefits For General Population

Literature supports the cardiovascular (CV) health benefits of PBDs, including reductions in obesity, hypertension, Type 2 Diabetes mellitus, and ischemic heart disease4-8 (Figure 1) as well as all-cause and CV mortality risk.9-10 Per the AHA/ACC CVD Primary Prevention Guidelines, PBDs are recommended based on various studies including the PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial, with an approximately 30% reduction in MI, stroke, or CV mortality with the Mediterranean diet; a post-hoc analysis showed a 41% mortality rate reduction with more plant-based food intake over animal product intake.11 Furthermore, the Adventist Health Study-2, which showed a 61% increase in mortality with animal protein versus plant-based protein.12 The 2021 ESC CVD primary prevention guidelines cite a 26% stroke risk reduction with three to five daily servings of fruits and vegetables and a 4% CVD risk reduction with additional servings.13-15

Benefits For Women

While most PBD research applies to mixed-gender populations, its impact on women remains unclear. Sex differences in CV health between men and women, including vascular biology and hormonal influences, may result in sex-differences in CV outcomes when using a PBD. Most recently, a 2021 prospective cohort study in the Women's Health Initiative evaluated over 120,000 post-menopausal women on the Portfolio diet (seen in Figure 1). The Portfolio diet contains 4 cholesterol-lowering foods with known CVD benefits, including improvement in dyslipidemia. This study found an 11%, 14%, and 17% risk reduction in CVD, coronary heart disease, and heart failure, respectively,16 highlighting CV health benefits in post-menopausal women.

Future Research Directions

Although current literature encourages PBDs for CVD primary prevention, further studies are needed to compare different PBDs. Recently, studies have adopted indices to evaluate PBD quality: the healthful plant-based index and unhealthful plant-based index2 (Figure 1). The healthful plant-based index weighs healthy plant-based foods positively and less healthy plant-based foods negatively. In contrast, unhealthful plant-based index weighs less healthy plant-based foods positively and healthy plant-based foods and animal products negatively. While these indices are useful for research studies, they are not patient friendly. Furthermore, it is necessary to determine ideal PBDs for different women: post-menopausal, pregnant, pre-menopausal non-pregnant, with and without CVD risk factors, etc.

Tools For Access and Adherence

In addition, interventions are needed to promote PBDs (seen in Figure 1). Clinicians and researchers will need to develop patient-friendly tools to create custom PBDs based on their CVD risk profile, including other cardiometabolic, psycho-social, and genomic risk factors. These tools may involve mobile applications for women to determine their CVD risk and ideal PBD; mobile applications are shown to improve CVD modifiable risk factors.17 Additionally, improving access to PBDs for women limited by time and resources is important (Figure 1). It is time nutrition went from a "one size fits all" approach to a personalized component of CVD primary prevention.

References

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e596-e646.

- Visseren FL, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. , ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies With the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J 2021;42:3227–3337.

- Satija A, Hu FB. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2018;28:437-441.

- Dinu M, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Sofi F. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(17):3640-3649. doi:10.1080/10408398.2016.1138447

- Kim H, Caulfield LE, Garcia-Larsen V, Steffen LM, Coresh J, Rebholz CM. Plant-Based Diets Are Associated With a Lower Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Disease Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality in a General Population of Middle-Aged Adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(16):e012865. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.012865

- Remde A, DeTurk SN, Almardini A, Steiner L, Wojda T. Plant-predominant eating patterns - how effective are they for treating obesity and related cardiometabolic health outcomes? - a systematic review [published online ahead of print, 2021 Sep 8]. Nutr Rev. 2021;nuab060. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuab060

- Gibbs J, Gaskin E, Ji C, Miller MA, Cappuccio FP. The effect of plant-based dietary patterns on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled intervention trials. J Hypertens. 2021;39(1):23-37. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000002604

- Johannesen CO, Dale HF, Jensen C, Lied GA. Effects of Plant-Based Diets on Outcomes Related to Glucose Metabolism: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:2811-2822. Published 2020 Aug 7. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S265982

- Quek J, Lim G, Lim WH, et al. The Association of Plant-Based Diet With Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Prospect Cohort Studies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:756810. Published 2021 Nov 5. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.756810

- Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Spiegelman D, et al. Healthful and Unhealthful Plant-Based Diets and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(4):411-422. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.047

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med 2018;378:e34.

- Tharrey M, Mariotti F, Mashchak A, et al. Patterns of plant and animal protein intake are strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality: the Adventist Health Study-2 cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2018; 47:1603–12.

- Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014;349:g4490.

- He FJ, Nowson CA, MacGregor GA. Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet 2006;367:320–326.

- Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Hercberg S, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Nutr 2006;136:2588–2593.

- Glenn AJ, Lo K, Jenkins DJ, et al. Relationship between a plant‐based dietary portfolio and risk of cardiovascular disease: Findings from the women's health initiative prospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e021515.

- Coorey GM, Neubeck L, Mulley J, Redfern J. Effectiveness, acceptability and usefulness of mobile applications for cardiovascular disease self-management: Systematic review with meta-synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018;25:505-521.

This article was authored by Najah Khan, MD, and edited by Bindu Chebrolu, MBBS, FACC.

This content was developed independently from the content developed for ACC.org. This content was not reviewed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) for medical accuracy and the content is provided on an "as is" basis. Inclusion on ACC.org does not constitute a guarantee or endorsement by the ACC and ACC makes no warranty that the content is accurate, complete or error-free. The content is not a substitute for personalized medical advice and is not intended to be used as the sole basis for making individualized medical or health-related decisions. Statements or opinions expressed in this content reflect the views of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of ACC.