Current State of Point-of-Care Ultrasound Curricula

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), and more specifically focused cardiac ultrasound, is leading the diagnostic forefront of bedside clinical cardiovascular assessment. The ears through which we previously relied on for cardiac auscultation are now being complemented by direct visual assessment ultrasonography.

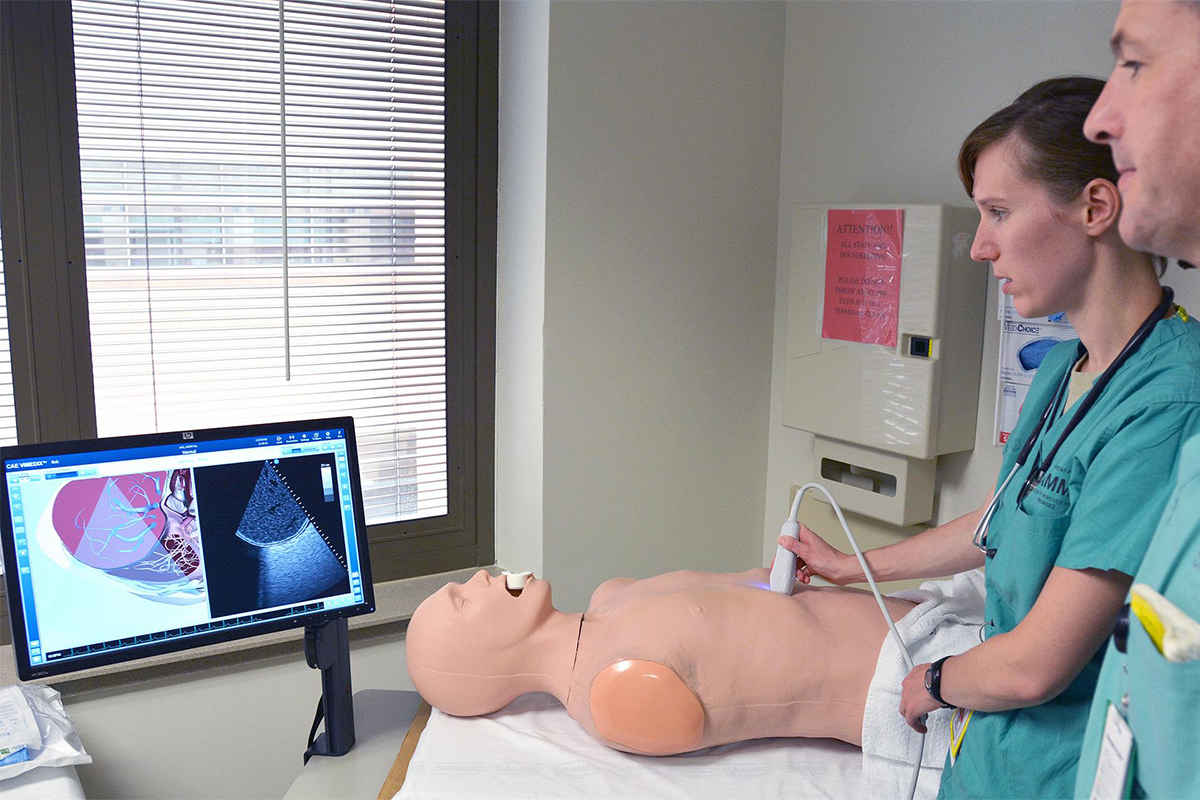

Whereas previously this would require a cumbersome machine and specialized sonographic expertise to acquire images, as well as rigorous years of training for accurate clinical interpretation, it is now commonplace for medical professions in various capacities and specialties to be acquiring and interpreting ultrasound images and incorporating them in their minute-by-minute decision making.

Thus, there has been a significant push to include bedside ultrasound in medical school and postgraduate training. Before making new suggestions on how best to teach POCUS, it is worthwhile to take a step back and review what has previously been published.

A majority of the literature has focused on curricula for internal medicine, emergency medicine residents or hospitalists. Along this line, Mira T. Keddis, MD, et al., studied the effect of a simulation-based training module during intern orientation on POCUS image acquisition confidence.

They found improvement in confidence in the use of ultrasound to identify various organ structures, including the inferior vena cava, internal jugular vein, pleural effusion and ascites.

Like many other curriculums that have been published, the metric of improvement in learner skill was a self-reported confidence scale which has inherent bias.

In another study, Christopher J. Smith, MD, et al., described a six-month curriculum comprised of sequential organ focused workshops with longitudinal peer group and individual practice, as well as didactic lectures given to clinician-educators with the goal of creating a faculty focus group that can educate future residents.

Images obtained by study participants were scored and compared with images obtained by cardiology fellows who had completed level I echocardiography training.

They showed that although hospitalists were as efficient as cardiology fellows in image acquisition, the quality of the images was inferior. Notably, this study did not assess interpretation of the acquired images, let alone integration of the clinical information.

These studies are just two examples of many published curricula that are self-credentialed and without multicenter validation or standardization.

Likely the most rigorous curriculum published was developed by Bruce J. Kimura, MD, FACC, and his team at Scripps Mercy Hospital in San Diego, CA. By using evidenced-based protocols, teaching to proficiency goals and testing learner performance, they were able to successfully implement a sustainable training program in focused cardiac ultrasound.

They developed a "quick look" ultrasound protocol assessing the carotid bulb, LV/RV function, pleural and pericardial space, inferior vena cava, and abdominal aortic called the CLUE criteria.

The material was taught in a multidisciplinary and longitudinal manner consisting of twelve monthly lectures with hands on scanning practice. The skill of acquiring images was initially taught by sonographers and reinforced by educators on cardiology rotations.

This curriculum persisted for the entire three years of residency by which time many residents had performed more than 100 studies. Residents were rigorously evaluated with a clinical examination testing technical skills in acquiring images, diagnostic criteria knowledge and discussing clinical findings in an oral question-answer format.

The curriculum just described represents the most sustainable and integrated curriculum published in the literature thus far.

The question remains, however, can this be replicated in other programs and what would be required in order to implement that?

The authors of the CLUE protocol curriculum reflected on the process of developing the program and came up with four questions that are vital to answer before setting up a curriculum:

- How will ultrasound be used in the program? As a physical examination technique or "limited ultrasound" study?

- How will the curriculum be structured? A vertical structure in which a foundation is built upon with repetition or a horizontal structure involving teaching techniques at separate unrelated points in time over the course of the program?

- What resources are available? Will there be resources available for mandatory participation or only elective participation?

- What learning considerations are specific to ultrasound? Physical skill or didactic knowledge or both?

As many medical educators are studying how to incorporate POCUS into existing ultrasound curricula, the aforementioned guiding considerations are crucial to reflect upon.

POCUS is now the cornerstone of bedside diagnostic cardiac assessment and we as the cardiology community should take responsibility of shaping the education of future learners.