Affecting the Landscape of Cardiology and Cardiac Imaging: An Interview With Rebecca T. Hahn, MD, FACC

How did you choose medicine and cardiology?

Internal medicine requires skills in both diagnostics and treatment, and allows direct interaction with patients.

Medicine requires an ability to not only follow algorithms but also think out of the box.

Cardiac physiology and pathophysiology were the most fascinating to me, and anatomy was my favorite preclinical subject in medical school. Echocardiography combined diagnostics, 3D cardiac anatomy and cardiac pathophysiology.

Which challenges did you go through as a woman in cardiology?

Having trained in the late 1980s, there were very few women as role models in cardiology. Luckily, one of those role models was an echocardiographer, and perhaps also influenced my choices.

At Cornell, I was the fourth woman in the program and the only woman to require "maternity leave" during the fellowship.

Since there was no maternity leave policy at that time, I depended on the understanding and support of my two male colleagues in the program – I was very fortunate to have their support, along with the support of my husband.

As a young attending, I had two separate interactions that epitomized the difficulties of those times. The first was when I requested to work part time to care for my young family. Many in academia believe this somehow shows a lack of commitment.

I am sure there are many who believe that in order to advance in the academic world, you have to: 1) decide on an area of research early in your career and stick to it, and 2) be willing to sacrifice time with your family to advance your career.

I was not able to go part time and keep my academic position, so I bought a professional workstation to allow me to work at home after the kids went to sleep. I also did not attend a national cardiology meeting for about 10 years.

It is not surprising that recent studies have shown that "adverse job conditions" and "interference with family life" are the top two medicine resident perceptions of the field of cardiology.

This statistic has to change if we want to not only attract women but also men into this field.

The second challenge I went through as a woman in cardiology was when I asked for a raise to make my salary comparable to my male colleagues. I was actually told, "You don't need the money, your husband works."

Nowadays, that statement would have significant repercussions. It was not only demeaning on so many levels but also irrelevant.

I made my arguments and got the raise.

Describe how you got started in interventional echo before there was "interventional echo."

It is truly a story of being at the right time, at the right place and with the right set of skills.

In 2007, I was the director of the echo lab at North Shore Hospital and realized that administration was not a skill set that I possessed. I was an echocardiographer, who loved to teach and wanted to be back at an academic institution. Linda D. Gillam, MD, MACC, recruited me to Columbia University just as the PARTNER trial began.

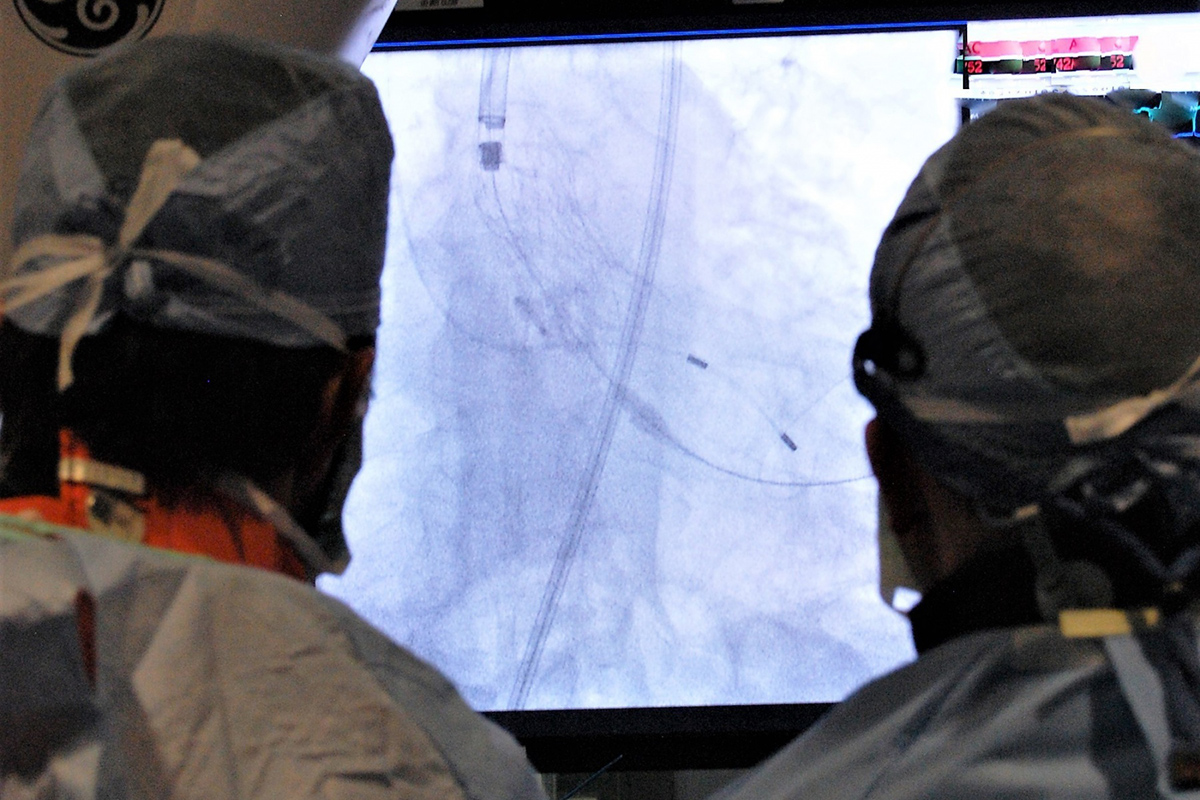

After a few short months of experiencing the innovation and comradery of the interventionalists – led by Martin B. Leon, MD, FACC – I was hooked. Leon rapidly acknowledged the need for imaging specialists early on, and by late 2009, I was taken out of the echo lab and worked entirely in the Center for Interventional and Vascular Therapy – the Structural Heart and Valve Center was formalized a few years later.

Leon gave me my new title and in doing so, coined a term for a new subspecialty: interventional echocardiography. As one international colleague astutely said, "You are Marty's eyes."

Tell us the story of the first TAVR you were ever involved in.

I do not remember the very first TAVR, but one of the first cases I was involved in transformed the way I look at every structural case – with an open mind! It is not a good story because I think of the mistake I made in that case every day.

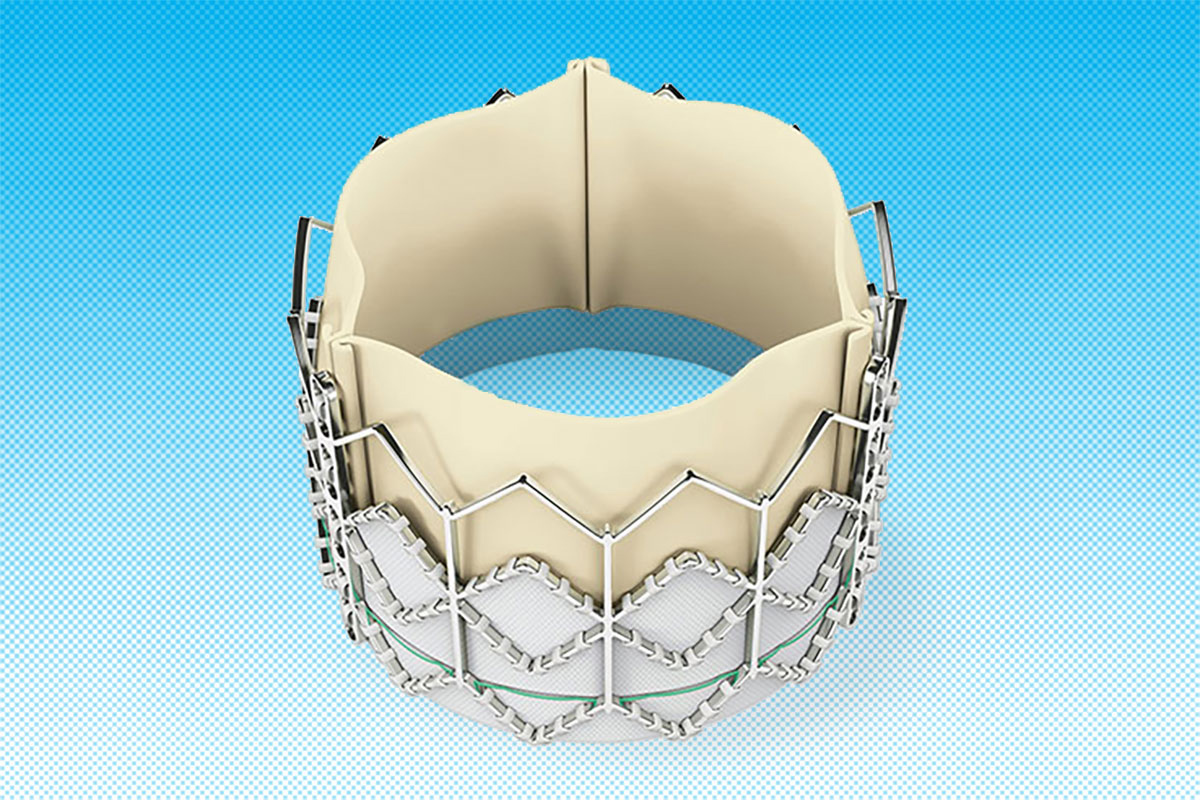

In 2007, we actually sized the transcatheter valves using a sagittal plane annular dimension. We had to oversize by up to 10 percent because little did we know, we were accommodating for the fact that the annulus is elliptical and the sagittal plane is the minor axis.

I had not thought about the anatomy of the aortic root much until after that day, but the annulus is virtual, defined by the hingepoints of the three cusps.

Thus, in the sagittal plane, only the right coronary cusp hinge is seen and the fibrous trigone may not have calcium at the level of the virtual annulus. I erroneously measured the annulus from the RCC hinge to a speck of calcium in the trigone which was above the virtual annulus, making the annulus too large for the devices available at the time.

The patient did not receive the TAVR, and I think about that patient all the time.

Since then, we have published extensively on the correct way to measure the annulus and devised a method to measure annular perimeter and area from 3D TEE. We have taken all our complications and learned from them, developing algorithms for avoidance and rapid diagnosis of complications.

We continue to explore new ways of imaging and work with the ultrasound companies to advance interventional imaging.

Which challenges did you face at the beginning of your interventional echo career?

Luckily, I was relatively protected within the institution as a salaried employee of the cath lab. However, every time I got on the podium, I was met with skepticism. Why would an imager need to be part of the structural heart disease (SHD) team?

In the end, guidelines and consensus statements have changed because of our model of the Heart Team, and for that I am very proud.

Where do you see the future of SHD intervention? Where do you see the future of SHD imaging?

These two questions are intimately tied together because of the early decision by Leon to bring an imager onto the SHD team. Now, the team involves the device companies and ultrasound companies too!

As device companies and ultrasound companies begin to talk to each other, the innovation will expand exponentially since everyone now agrees that you need to "see" in order to implant. Imagers and sonographers are now being hired by device companies.

Innovation is now dependent on imaging input. About two years ago, we discussed how our job satisfaction could not be higher, but indeed it seems to get more and more fun as the field continues to advance and our roles continue to expand.

How can we better advocate for our needs as SHD imagers?

I realize that our situation is unique. We are salaried, and the institution had to be (and was) convinced of the value of our skills. This is a form of revenue sharing by the cath lab, of course, but there are other ways of doing that.

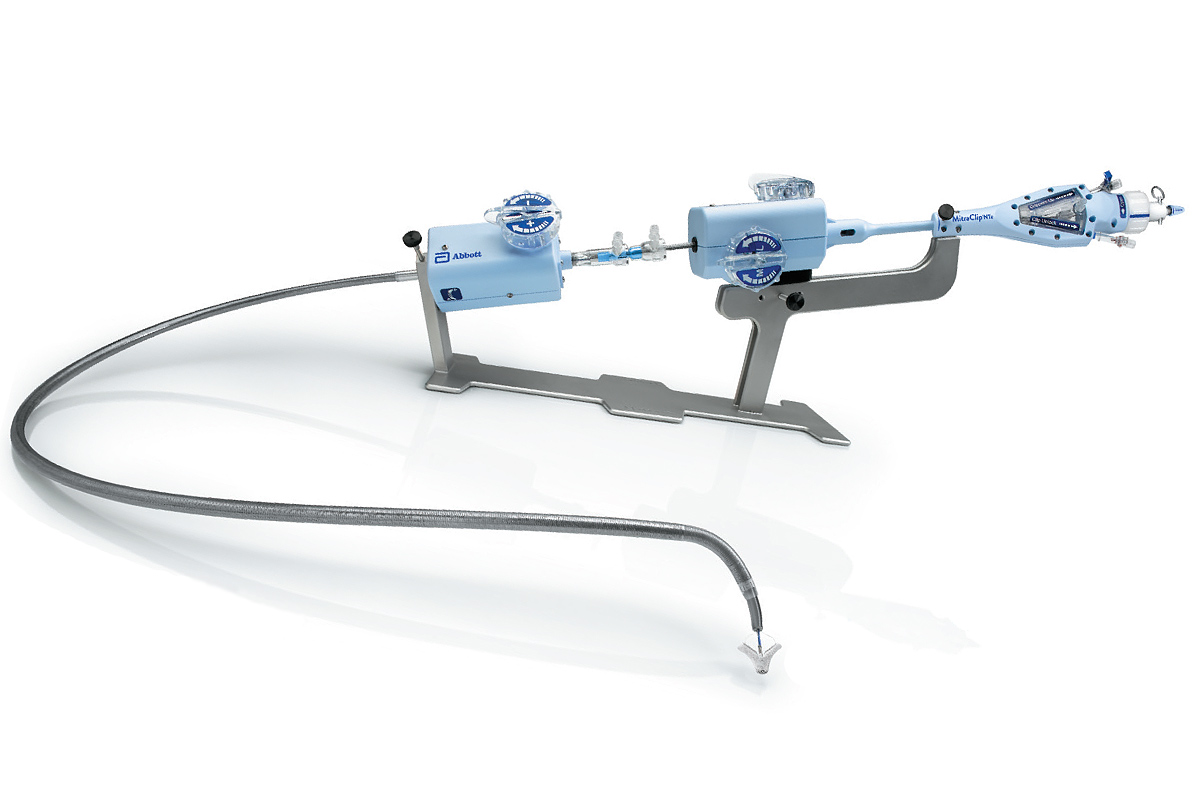

I was just at another institution where the interventionalists shared his RVUs for MitraClip with the imager – after all, he told me, how could we place the device without the imager?

This was an individual interventionalist's recognition of the role of the imager. This practice could be generalized if the definition for "co-operator" was changed to allow that physician to be an imager –then, we would not be relying on the consideration of individuals, but it would become an institutional norm.

Alternatively, interventions could be assigned a higher value by the institution.

We should all advocate for the field through every avenue possible, and keep pushing our societies and device companies to also advocate for change.

Through your involvement in social media, how do you feel it is affecting the landscape of cardiology and cardiac imaging?

Since so many cardiologists may be getting the majority of their information on Twitter, I felt compelled to join the revolution in June 2018.

Social media is a powerful educational tool with some limitations.

First, the tweets are short, and to distill an entire article into a single tweet is quite difficult. Thus, there is always an inherent bias in what and how we choose to tweet information.

I try to choose articles carefully and present them objectively. If you can see through any inherent bias in the source of the information, information in the tweet and primary source, then make your own decisions about which information is not only true but worth knowing, this tool will indeed change the way we practice cardiology.

Which top three points of advice would you give to aspiring SHD imagers?

First, your friends, significant other and colleagues can be your greatest support and inspiration, so choose your entire "team" well.

Second, do not be afraid to ask for help or support – it is not a sign of weakness but rather of determination. How many of us can say that we did not have help early in our career? Finding mentors who can help you advance your career is part of having the right support.

Third, never stop learning. This new subspecialty requires the greatest skill for the fewest number of procedures, and so others may have the experience that your institution lacks.

Thus, learning from personal experience and from your imaging colleagues around the world will help advance your own expertise. In doing so, you will help all of us in SHD imaging promote this new subspecialty and push our societies to define the skill set and training required to perform these procedures.