Eight Minutes and 46 Seconds That Should Change the Way You Practice Medicine

SOURCE: NBC NEWS/Dragon Wok Security Camera Footage

SOURCE: NBC NEWS/Dragon Wok Security Camera Footage

Watching the final moments of George Floyd's life was bearing witness to a complete disregard for human life. What makes the kind of total disregard for an entire population of human beings in this country possible is the denial of the very notion that Blacks are human at all.

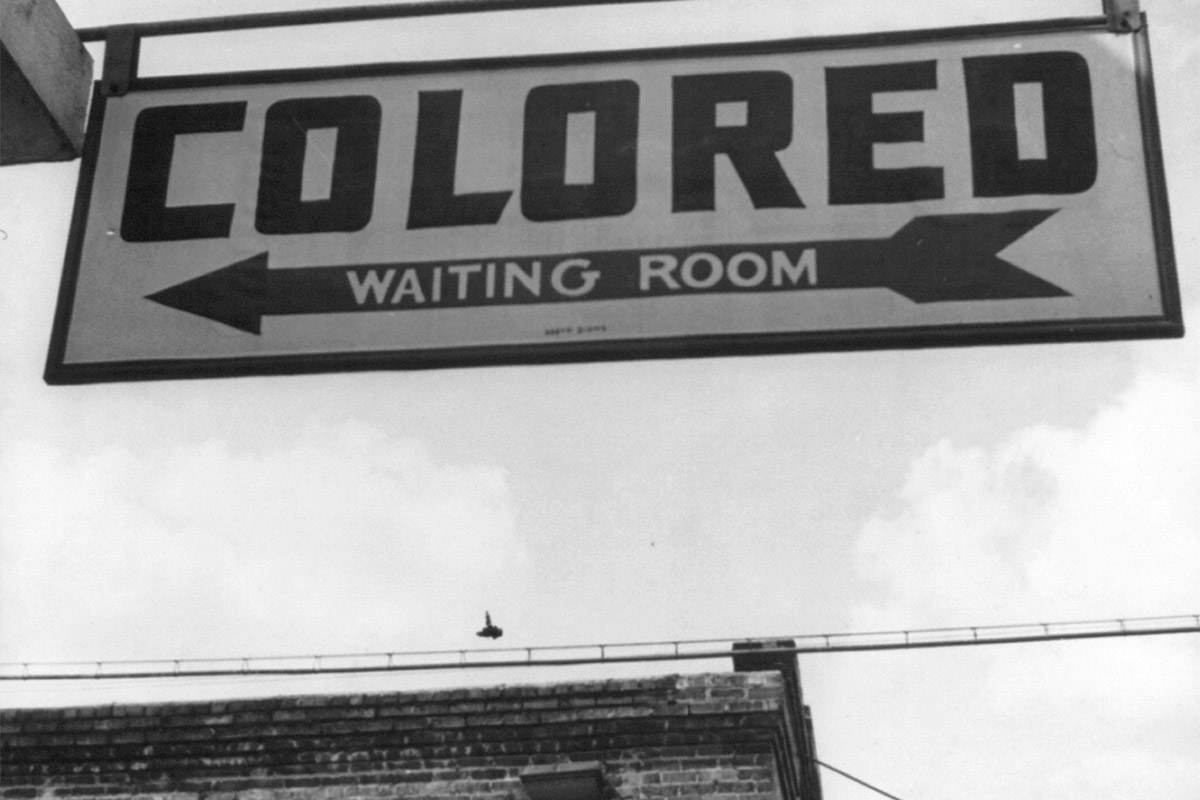

Black people have been systematically dehumanized in this country for hundreds of years.

As a result of this dehumanization, we have too often come face to face with the violence of police officers against Black people, and recently, we witnessed the painful murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police.

As physicians, we need to come to terms with the fact that this violence against Black people has a deeply rooted history in another institution that pledges to "do no harm" – medicine.

In fact, the only institution that can rival the amount of violence visited upon Black bodies in America by police is the institution of medicine. Moreover, the history of many medical discoveries begins with violence against Black people.

In the 1830s, the South Carolina Medical College advertised to prospective students that "no place in the United States offers as great opportunities for the acquisition of anatomical knowledge, subjects being obtained from among the colored population in sufficient number for any purpose, and proper dissections carried on without offending any individuals in the community!!"

In recent times, this legacy has continued but has just taken different forms. One form of the modern day violence on Black people in medicine that is overlooked is the silent disregard for clinical impact of racism on Black people.

Medicine has traditionally viewed racism as a sociopolitical issue but has not recognized it for what it is: a direct health risk. Pervasive, unrelenting systemic racism has proven short- and long-term negative cardiovascular health effects.

However, despite the deleterious impact on cardiovascular health, institutionalized racism and violence experienced by Black patients in the U.S. is currently not accounted for by any tangible measure in risk assessment, risk prediction or clinical management.

More broadly, social determinants of health in general, which have proven to be some of the most powerful predictors of cardiovascular disease outcomes, are also completely missing from clinical risk prediction.

The disproportionate burden of social risk factors among blacks in this country are directly tied to structural racism in this country. Medicine has stood silently by, generating TIMI, GRACE and PCE scores while persistently ignoring racism's outsized health impacts, silently violating Black patients' rights to equitable care.

This silence is an act of violence.

Seeing what you saw recently though, would you think to consider the impact of what George Floyd experienced on his cardiovascular health? Let's imagine for a moment that George Floyd had the same experience but that he survived.

Imagine he did not die.

He shows up to your clinic. Would you have asked him, "Have you ever had your neck crushed into the pavement for eight minutes and 46 seconds until you couldn't breathe?"

Do you think his experience would be relevant to his visit with you?

You should.

If you do not think that the experience that he had would have an impact on his ability to comply with the medication you might prescribe, you are wrong.

If you do not know that his experience changes his likelihood of cardiovascular events, cardiovascular disease risk factors and death, you are misinformed.

During the visit, does he trust you? Because if you think that what he experienced does not impact his trust in you, in the institution of medicine – you are wrong.

Do you think his experience would have an impact on his stress level, blood pressure, heart rate or myocardial stress? Do you think it might lead to mental health disturbances including depression or PTSD?

In fact, the health impacts of racism are arguably greater in cardiology than in any other field; when a person is always in fight or flight mode just because of the color of their skin, negative impacts on the cardiovascular system are some of the most severe.

Racism and the experience of racism hold vice grips around the metaphorical windpipes of your Black patients that you cannot see when they walk in the door.

They have experiences that most likely will not have been captured on film.

But the hard truth is: all of your Black patients have experienced some level of systematic racism and many forms of violence on the basis of their race in this country. And if you do not ask about it you will not know about it.

For every George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Rayshard Brooks, there are many that survive these most extreme acts of racial violence. They walk into your office every day, and if you do not assess the impact of racism on their health, you deny them a part of their humanity.

What is more, despite all of your good intentions as a clinician, you will most likely inaccurately estimate their cardiovascular risk. If you are systematically underpredicting risk, you are systematically undertreating.

So how do we change our practice in light of this? Ask about racism and its effects on your patients' lives. Ask about experiences of violence. Ask if your patient has a family member or friend that has been a victim of violence and racism.

Insist that scientists and researchers do the work needed to identify the most efficient method of screening for and quantifying the health impacts of racism, an important and overlooked social determinant of health. Deepen your empathy and hesitate in your rush to judgement.

Blacks in this country are battling with stress and strain that is in direct conflict with any aspiration for health and well-being.

Appreciate that.

So if George had come to see you, instead of writing, "This is a 56-year-old male with a history of no-shows and noncompliance with his medications," consider whether the note should begin with this acknowledgement in your mind, "This is a 56-year-old African American man, recently violated, burdened by violence, managing unimaginable stressors, yet despite all of those barriers to him being here, he presents for one fair shot at his health today."

Think to yourself, "Today, he deserves my best shot at offering him equitable, dignified care and the best modern medicine has to offer." Instead of judgement, offer him inquiry, empathy and a sincere desire to understand his actions, beliefs and health in the context of his experiences.

Offer him humanity.

Racism is pervasive in the U.S. On May 25, 2020, we saw the most literal expression of this hate, but every Black person has had some part of themselves choked out, some with the accumulation of countless covert microaggressions, and some with what we saw on that film. And it is hard but necessary to acknowledge that by virtue of being socialized in a system built on white supremacy, you are complicit in racism whether you know it or not.

It will take active resistance and deliberate concerted action to undo this miseducation. The graphic view of violence and hatred that was the end of George Floyd's life was an entire syllabus on systemic, institutionalized racism and what is broken in America.

Learn the lesson that this tragic turn of events brings. It teaches us that the deeply rooted belief in this country that Blacks are less than human persists. It is on us as physicians to do our part to denounce dehumanizing practices in medicine.

Ignoring the experience and impact of racism by Black people in medicine is another kind of dehumanization and violence enacted on Black bodies.

Daily discrimination and systematic institutionalized racism are the metaphorical knee on the neck of every Black person in this country.

Let this be a metaphor etched into your consciousness. If you let watching George Floyd's tragic end change the way you see the world, you learned an important lesson.

If you do not let this change the way you practice medicine, you missed your best chance to make an important difference.

Do not let that happen. Be human. Acknowledge and respect the experiences and the humanity of your Black patients.

If you do, it will save lives.