From Caregiver to Patient: My First-Hand Experience Surviving COVID-19

"Experience is the best teacher and the worst experiences teach the best lessons." – Author Unknown

As New York City's medical community was learning about the earliest local COVID-19 cases, the first week of March 2020 was filled with mixed feelings of fear, anxiety, skepticism and frustration.

Frustration especially for the small number of trainees and providers who saw what was coming to New York City, while most others at their own institutions were in disbelief.

The distinction between non-COVID-19 patients under investigation and COVID-19 patients in hospitals started fading away quickly, as more and more hospitalized patients tested positive.

This exponential growth of contagion changed the lives of doctors, nurses and all other health care workers both inside and outside of hospitals.

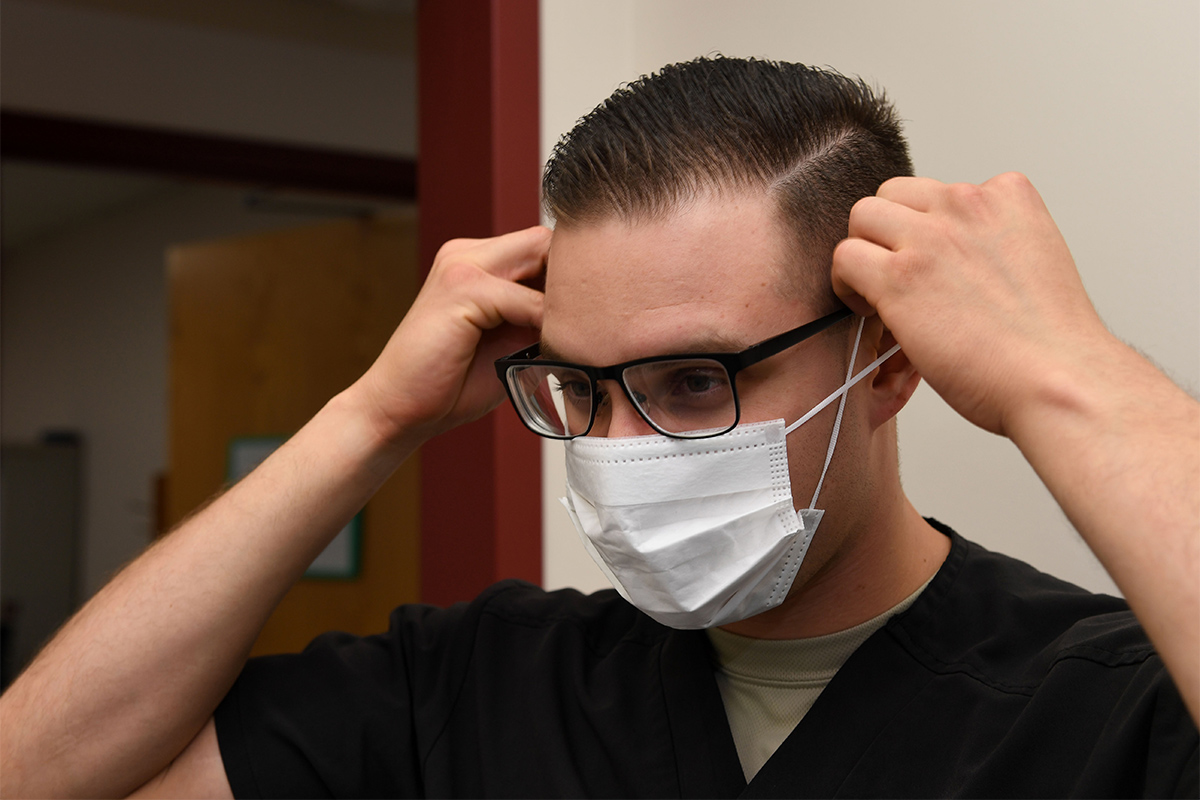

While treating COVID-19 patients, a series of rapidly changing policies from wearing N-95 masks for airborne precautions to wearing only surgical masks for droplet precautions to eventually donning a full range of personal protective equipment added to the uncertainties and worries of health care workers.

Currently, virtually all of our hospital's medical/surgical beds are occupied by patients unable to breathe or talk, desaturating with bilateral pneumonia, unstable vitals, clinically evident dehydration and persistent high-grade fever.

Surgical, medical, cardiac and cardio-thoracic ICUs have all become COVID-19 ICUs, and new dedicated COVID-19 ICU areas are being actively formed essentially out of thin air.

Prolonged need for ventilatory support once intubated and concomitant multiorgan failure including frequent need for continuous renal replacement therapy put an enormous strain on ICU bed availability. Protracted hospital courses in conjunction with the nonstop influx of new COVID-19 patients creates a vicious cycle of mismatch between care setting and patients' acuity level.

The crunch for ICU beds leaves many critically ill patients being managed on telemetry floors and unstable patients requiring telemetry monitoring on regular floors, putting extraordinary stress on the health care teams involved.

Hospitals across New York City have adopted strict no visitor policies, resulting in an unprecedented struggle for patients without their loved ones around them and for their providers trying to provide some emotional support while simultaneously keeping themselves safe.

Hypoxemic patients frequently require use of high-flow nasal canula, an aerosol-generating oxygen therapy posing a significant threat of cross-infection to health care workers. The frequent need to prone patients creates a logistical nightmare as we attempt to manage their needs with limited resources.

Multiple daily overhead announcements of "code 3" – Montefiore's code for cardiac arrest – and "anesthesia-respiratory stat" work against our fighting spirit. Intubation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation are aerosol-generating procedures with higher risk of disease transmission, which presents the unique existential anguish of trying to save patients while protecting the providers.

While fighting this battle against COVID-19, many of my colleagues and friends became sick and suffered the illness. Eventually, I too experienced the disease first-hand and faced the dreadful uncertainties it brings along with it.

I distinctly remember how it started: we came back from grocery shopping on a Friday and I was looking forward to a quiet weekend. While watching the evening news, I experienced a few bouts of dry cough and felt feverish. My first instinct at that moment was to isolate myself from my wife and two-year-old daughter.

My wife brushed away the idea, saying my response was exaggerated. When I checked my temperature, it recorded 100.8, and I went ahead with isolation right away. The next day, with a lingering low-grade fever, I went to ER and got tested for COVID-19.

While my wife was still in denial, my concern was how I would continue to effectively isolate myself in our small apartment with one bathroom. The thought of isolating myself for two weeks from my daughter, whom I hug and kiss countless times in a day, was unbearable.

Utterly confused and unsure of what was happening, she kept knocking on my door to play with me. It was heartbreaking to hear her cry and leave, while my words from inside could not console her.

Nights in particular were hard with a sense of extreme fatigue and temperature crossing 101 frequently. On day five, I noticed wheezing and difficulty talking, which progressed quickly over the next two days to shortness of breath and difficulty lying down.

As per my infectious disease specialist's recommendation, I started hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. After two days of taking them, my breathing continued to worsen and my oxygen saturation dropped to 92%.

I went to the ER again and an urgent CT chest showed significant changes that warranted admission to the Medical ICU for close observation. With a heavy heart, I conveyed the findings and the plan of care to my wife via text message as I could not talk at all.

With my infectious disease specialist's proactive approach, I was lucky to receive IV Tocilizumab on the day of my admission. Noticeably my fever was gone the next day, but I was still struggling to breathe and talk.

The following three days in the ICU were an unforgettable ordeal, as I was uncertain about the course this may take. Even worse, I could sense the despair and anxiety in my wife's eyes during our video calls as I still was not able to talk.

Fortunately, I was one of the lucky ones – with the prayers and good wishes from countless friends, well-wishers and loved ones, my breathing improved and I was discharged home with the recommendation of one week's isolation from my family.

The day I finally hugged my little daughter and wife, I felt like I got my life back.

I learned a lot from this ordeal; about the courage of frontline health care workers, the absolute importance of our loved ones and the crippling uncertainty of life – no one is guaranteed to still be here tomorrow.

In the midst of this pandemic, the most practical lesson is this: listening to your own body and recognizing even minor symptoms is critically important during this time, as this can help us initiate timely self-isolation that in turn can protect others.

Be vigilant, be proactive, and protect yourselves and your community before it hits close to home.