The Man Who Woke Up: Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, A Survivor's Story

There is a reason that all medical presentations begin with the patient's age. Age gives us insight into what conditions might be most likely to cause a given set of symptoms. It also frames our approach to treatment.

Should we be aggressive? Is there rehab potential? Can they make a meaningful recovery?

The older a patient gets, the more important these questions become.

However, age also acts as a chapter heading in the book of a patient's life. How far along are they? How much have they experienced? Life threatening sickness in an 85-year-old is, well, predictable.

For a 36-year-old, it is a tragedy.

That is why when the words FENTON 36M VFIB ARREST ER appeared on the small LCD screen of my pager, I reflexively shook my head. 36 is young. He had been brought in seconds earlier by EMS, so there was nothing in the chart. I headed to the ER.

I could not see him right away. He was surrounded by a gaggle of ER docs and nurses. A pack of family members stood in terror a few feet back. Two EMTs were standing at the foot of the bed, doing paperwork. They had backwards facing FDNY caps on. Vitals were scribbled onto one of the EMT's blue latex gloves.

I walked up and asked for some history, which they gave me in curt, professional sentences:

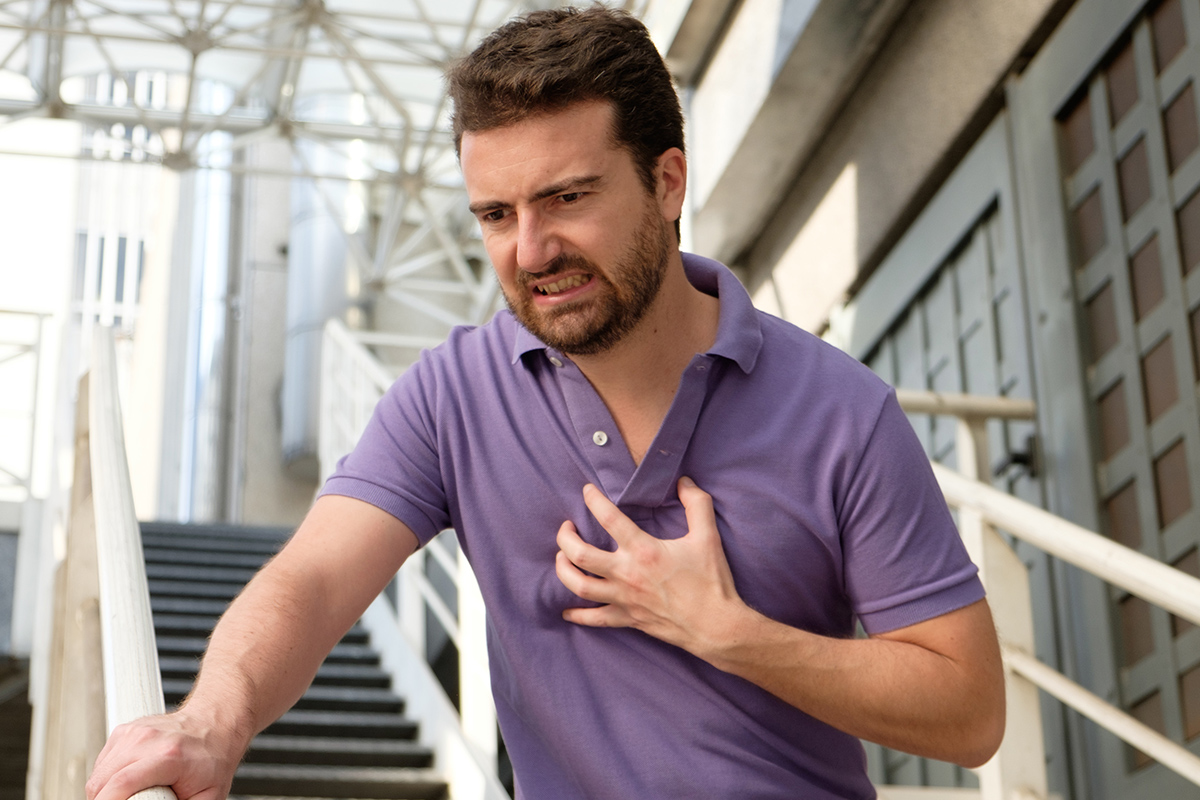

"Called to a mechanic's shop. 36-year-old male. No medical history. Patient was pulseless on arrival. Had been down for a few minutes before we got there, they had already started CPR. Coworkers said he was complaining of a racing heartbeat. Had palpitations earlier in the day too, they said. Intubated in the field. Shocked-times-one for Vfib, amio three hundred, five of epi. ROSC on arrival to ER. Currently, vitals stable."

They handed me the EKG. Normal rhythm...no signs of ischemia... but something jumped out. A subtle, sloping, early rise in the QRS complex with a short PR interval. A delta wave. Preexcitation. The patient had undiagnosed Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and it had just finished trying to kill him.

I pushed my way through the crowd of people to get a good look at him. He had a muscular, athletic build, with a short, neatly trimmed beard and a bald eagle tattoo down his left arm. The breathing tube emerging from his mouth, so common in the frail and dying, looked particularly unnatural in him. His body was shaking in short, jerky bursts.

Intermittently, his hands would rise in a folded position underneath his neck – decorticate posturing. His girlfriend was sobbing uncontrollably a few feet away. More and more family poured in by the second, running up to the ER stretcher and bursting into tears.

I examined him, got the EKGs and spoke with the ER. We would bring him up to the CCU and cool his core temperature to 91 degrees Fahrenheit to try to give his brain a chance to recover. His myoclonic jerking was extremely troubling, as was the amount of time he had been down for.

I hunkered down what I knew would be a brutal few days.

You learn a lot about someone by who comes to visit them in the hospital. I could tell Mr. Fenton was special. Generations of family came in waves – grandparents, parents, brothers and sisters, cousins, nieces, nephews, and his extremely devoted girlfriend.

I got to know them well. The stories poured in. Mr. Fenton would kiss his brother good morning every day at the mechanic shop. He undercharged those who could not pay in full. He took time off to nurse his grandmother back to health after she broke her hip.

This made it even more difficult to tell the gathered crowd – at least 20 strong at this point – how grim his outlook was. I described his accessory pathway, which had lurked for 36 years before rearing its head, which had likely conducted atrial fibrillation impulses at extreme speed to his ventricle.

I explained the heart in ventricular fibrillation. The brain's insatiable, unceasing need for oxygen. The outcome statistics for out of hospital cardiac arrest with bystander CPR. It was a grim conversation.

Some family members turned away to hide tears. Some stood stoically, absorbing the blows with stony faces. Some had to walk out of the room. Mr. Fenton lay motionless. There he was, right there, but he was also nowhere.

His girlfriend squeezed his limp hand as I talked. Nobody spoke when I finished talking. The mechanical wheeze of his ventilator filled the ensuing silence.

Squeee - hissss .... Squeee - hissss .... Squeee - hissss....

Two and a half days passed. He began to shiver uncontrollably from his core body temperature being frozen to nearly 10 degrees lower than normal. He developed an aspiration pneumonia and was started on antibiotics. His urine output slowed.

Each new development led to questions that had no good answers. Family members would pull me aside during the day ask blunt question.

"Doc… be honest with me. What are his chances?"

I gave answers, but they were elusive. Half-answers. I used words like "time," "hope," "damage," "don't know" and "concerned."

His family watched over him in shifts. They practically moved into the CCU. They made sure they were up to date on the latest labs and imaging. They brought the nurses and residents coffee and donuts.

But mainly, they waited.

Hunched over cell phones, gathered by windows, whispering in circles of two and three. They cried and they watched and they held one another and they waited.

Finally, the day arrived. It was the day I had been dreading. For most out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients, this is the day that breathless waiting and crossed fingers are converted into slumped shoulders and heads hung low.

I have done this so many times by now it almost feels routine. Rewarm the patient. Turn off the sedation. Wait for the patient to wake up. Call neuro. Order brain scans. Monitor labs, treat infections. Allow the reality of the situation to set in for the family: They never wake up. Call palliative. Plan for terminal extubation.

This time, though, was different.

Fifteen minutes after turning off the sedation, Mr. Fenton reached for his breathing tube. He bucked and strained against the vent. And then he made the sound that any one of us would have made in his position – he gagged on the breathing tube.

I exchanged glances with my resident. His eyebrows were raised in an expression that said: "Did you hear that?" After a few minutes, I stepped forward.

"Mr. Fenton, can you show me two fingers with your right hand?" All eyes in the room turned to his right hand. The arm it was attached to was littered with IV lines, tape and gauze.

The telltale purple coloration of venipuncture sites oddly colored his large bald eagle tattoo. The room was tense. An entire lifetime's worth of potential energy was pent up in our collective gazes at his hand.

Slowly, shakily, his second and third fingers extended up and away from the rest of his closed fist. Up they stood. He continued raising them until they flexed backwards towards his face.

Tension turned to shock. His girlfriend gasped and clutched his hand. His grandmother shouted, "Oh my god!" His brother rushed in and gave him a kiss on the cheek and whispered something in his ear.

When he pulled away, I could see tears streaking down his face. He was alive. And he was waking up. An hour later, the breathing tube was out. That evening, he was talking to us.

After making sure he was stable, he was transferred to a larger hospital for the definitive surgery to ablate the accessory pathway. He was sent for cognitive rehab.

Two and a half weeks after showing up as a digital printout on my beeper, he was discharged.

For weeks after he left, I could not stop thinking about him. It all seemed so implausible. He was so young! He should be dead! Well, he should be alive, but he had ventricular fibrillation out of hospital… he should be dead!

People simply are not supposed to survive events like these.

How did he?

It was almost as if his age – the intangible resilience of his body and the vigor with which he could hang on – had simultaneously been his tragedy and his success. The fact that he was so young was the underlying tension surrounding his hospital course.

It is why half the hospital was pulling for him to recover, why he ended up taking up so much time on rounds. He was all anyone could talk about.

But it was also the reason he was able to recover. It seemed to allow him to hold on. Would someone twice his age have been able to?

I imagine him as a young pilot faced with a malfunctioning plane caught in a nose-dive. Alarms blaring, oxygen masks dangling, he frantically pulls the yoke. He pulls and pulls and pulls.

When someone else might have given up, he gives a final, desperate heave. He regains control of the plane at the last moment. It levels out with the wings just touching the surface of the water, then rising off again into the morning mist.