Hospitals in Baltimore Partner With Faith Leaders to Address Vaccine Inequity

Early on in the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine in Baltimore, MD, officials began to sound the alarm that Black residents were receiving vaccines at a lower rate than white residents. Pastor Rodney Morton, a local faith leader, notes that initially there was a lot of reluctance to receive a COVID-19 vaccine due to the impression that it had been rushed to market, observing that calling the roll out Operation Warp Speed did not instill confidence. "The language used was not crafted to reach people and answer concerns," he said. "We needed to be informed and educated – we needed questions answered." Morton, senior pastor of Central Baptist, a church in west Baltimore with more than 600 members, worked to get the word out to his congregants from credible sources. When Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD, an African American woman, viral immunologist at NIH and a scientist who worked on the development of the Moderna Vaccine, spoke at a virtual event in Feb. 2021, Pastor Morton brought the video directly to his church service. "She looks like us – she sounds like us. And she was a lead scientist on the vaccine."

Pastor Rodney Morton, senior pastor at Central Baptist Church in Baltimore, MD. Click the image above for a larger view.

Pastor Rodney Morton, senior pastor at Central Baptist Church in Baltimore, MD. Click the image above for a larger view.

Baltimore Faith Leaders Get Questions Answered and Get Vaccinated

In March 2021, Pastor Morton worked with Olivia Farrow, JD, director of community engagement and Arif Khazi, MS, vaccine clinic director, both from Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital (SAH), to convene faith leaders from across Baltimore. "Faith leaders have the largest captive audience in Baltimore on a weekly basis," Morton said. He envisioned a meeting where church leaders from across the city had their questions answered by medical professionals from a trusted community partner like SAH, and then would receive the vaccine themselves. Farrow says SAH was thrilled to help convene the event that brought their Chief Medical Officer Jon D'Souza, MD, MBA, together with Baltimore pastors to get their questions answered, followed by the leaders receiving their vaccines. "It was a great opportunity to include local clergy in the discussion," Farrow said. But by late March, faith leaders were signaling other concerns. When Reverend Dr. Cleveland Mason senior pastor of Perkins Square Baptist Church, was asked what he was hearing from his parishioners about vaccine reluctance, he said, "Sure I've heard a little bit about Tuskegee and the like, but the main thing I'm hearing is, "When can I get my vaccine'?"

Digital Divide Impacts Vaccine Rollout

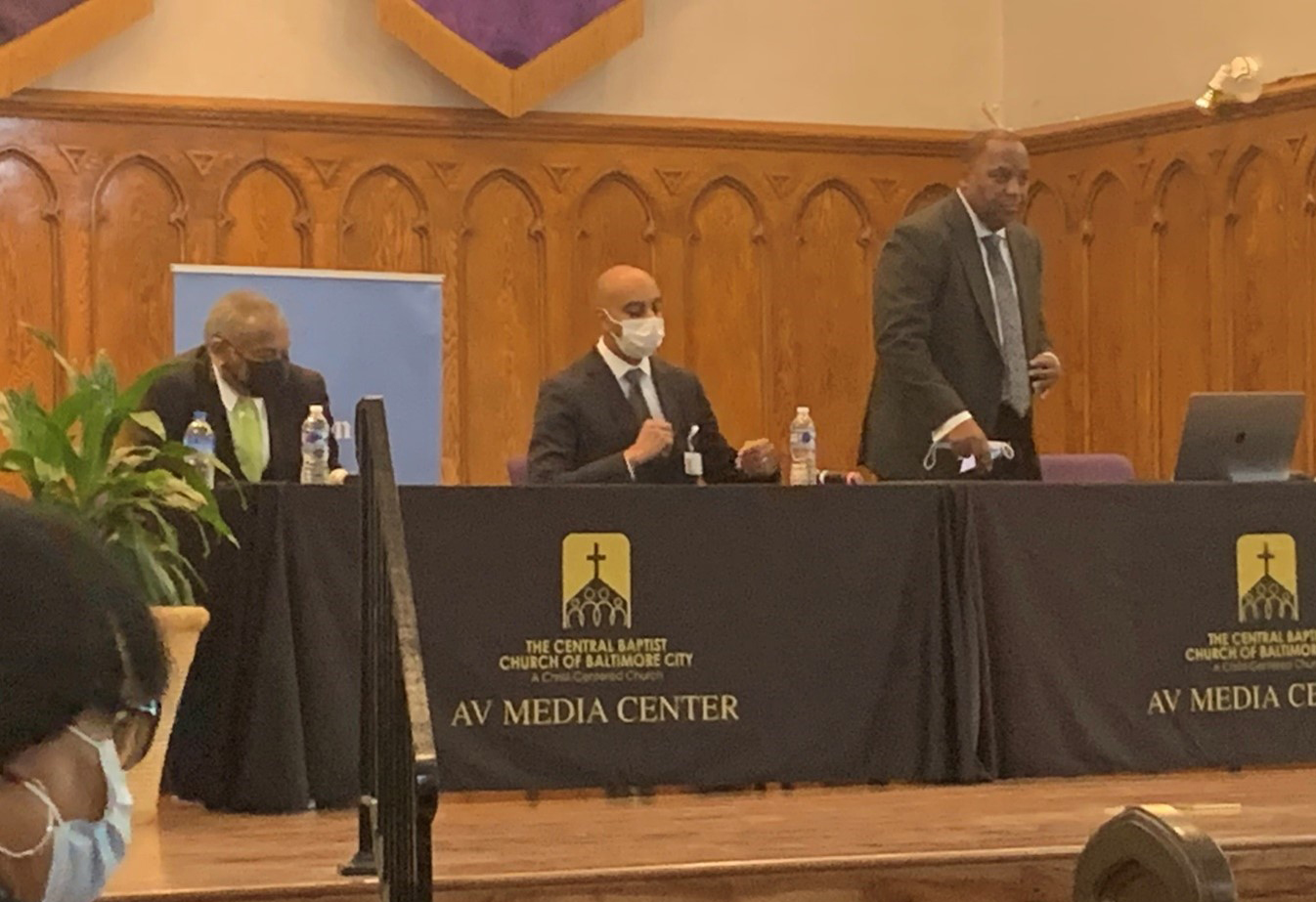

Reverend Dr. Cleveland Mason from Perkins Square Baptist Church, Jon D’Souza, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at SAH and Pastor Rodney Morton.. Click the image above for a larger view.

Reverend Dr. Cleveland Mason from Perkins Square Baptist Church, Jon D’Souza, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at SAH and Pastor Rodney Morton.. Click the image above for a larger view.

Both Farrow and Morton point to the digital rollout as a major cause of vaccine inequity in Maryland. As many ACC providers saw early on, the pandemic threw digital inequities – often called the digital divide - into sharp relief. Health care providers struggled to complete video visits with their patients who lacked reliable broadband access, digital literacy, and smart phones or computers. And yet when the vaccines started rolling out across Maryland, the only way for most citizens to schedule their vaccine was digitally through a centralized website. "People were getting up at four in the morning to get on their computers, and then the process was so complicated they couldn't figure it out. And those were the ones who had computers!" Morton said. SAH partnered with the Baltimore City Health Department Division of Aging to improve vaccine access to residents without adequate internet or social support. Working with SAH, Pastor Morton joined this partnership, and now supplies lists of residents needing the vaccine directly to the Division of Aging, which reaches out to by phone to get them scheduled and registered for their appointments. "At this point, about 70% of our active congregants are vaccinated," says Morton.

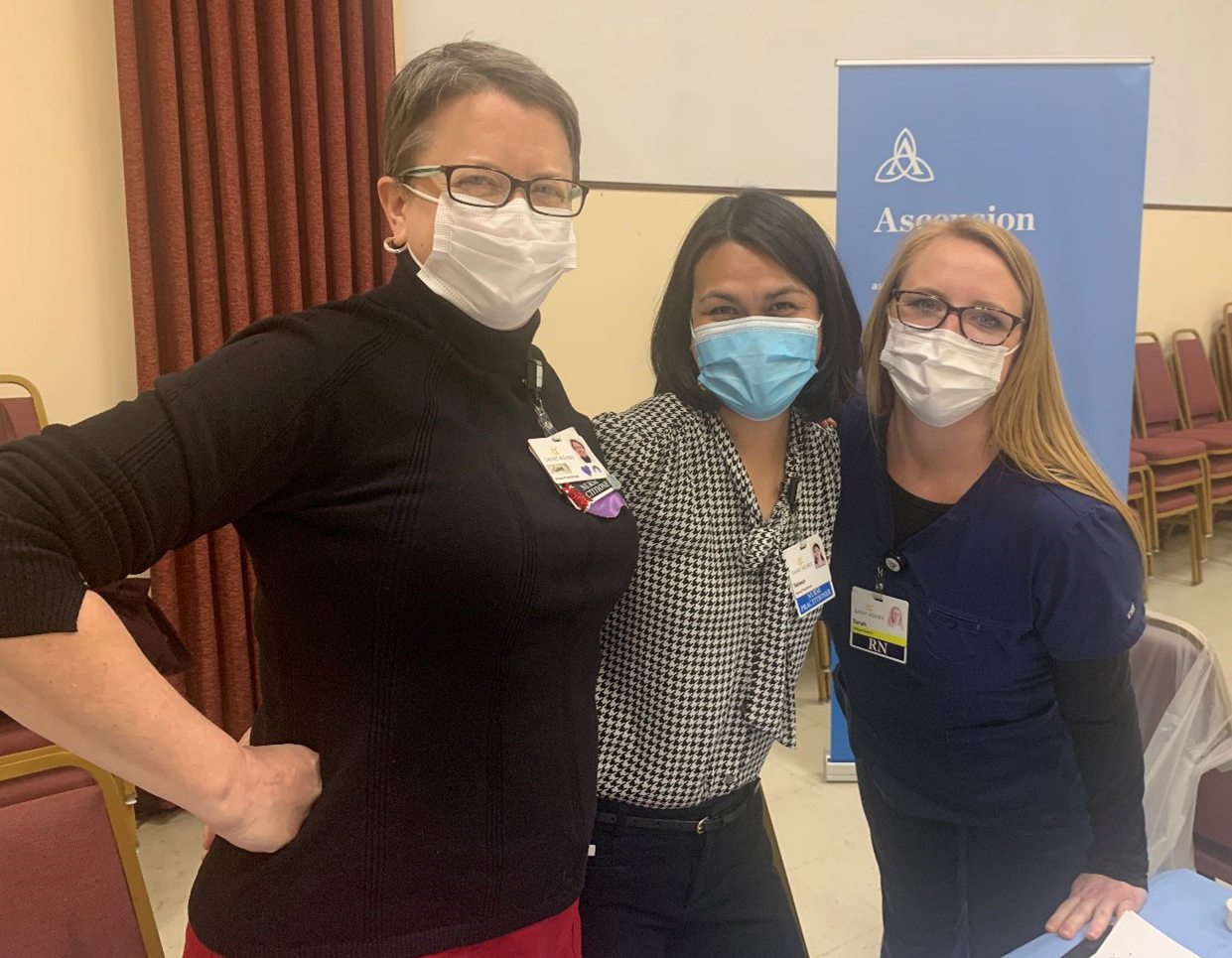

Jae Patton, MSN, CRNP, AACC, Neleen Orsal, MSN, CRNP, and Sarah Duvall, RN, nurses from SAH, getting ready to vaccinate faith leaders in Baltimore, MD in the church hall at Central Baptist.. Click the image above for a larger view.

Jae Patton, MSN, CRNP, AACC, Neleen Orsal, MSN, CRNP, and Sarah Duvall, RN, nurses from SAH, getting ready to vaccinate faith leaders in Baltimore, MD in the church hall at Central Baptist.. Click the image above for a larger view.

When asked about challenges for the future, Morton expresses concerns about young people not receiving the vaccine due to a false sense of security, noting "they receive information in different places." He also points to post-pandemic trauma and loss. When they are able to have their first in-person service, Central Baptist will hold a memorial service for the 22 members they've lost over the past year. "It's about restoring confidence," he says. For her part, Farrow is proud of the work that SAH continues to do in the community. "Through these continuing partnerships, inequities will diminish as a heightened understanding of the true needs of the community are identified and addressed."