Variations in Care, Part 3: Standardization and Supply Variations

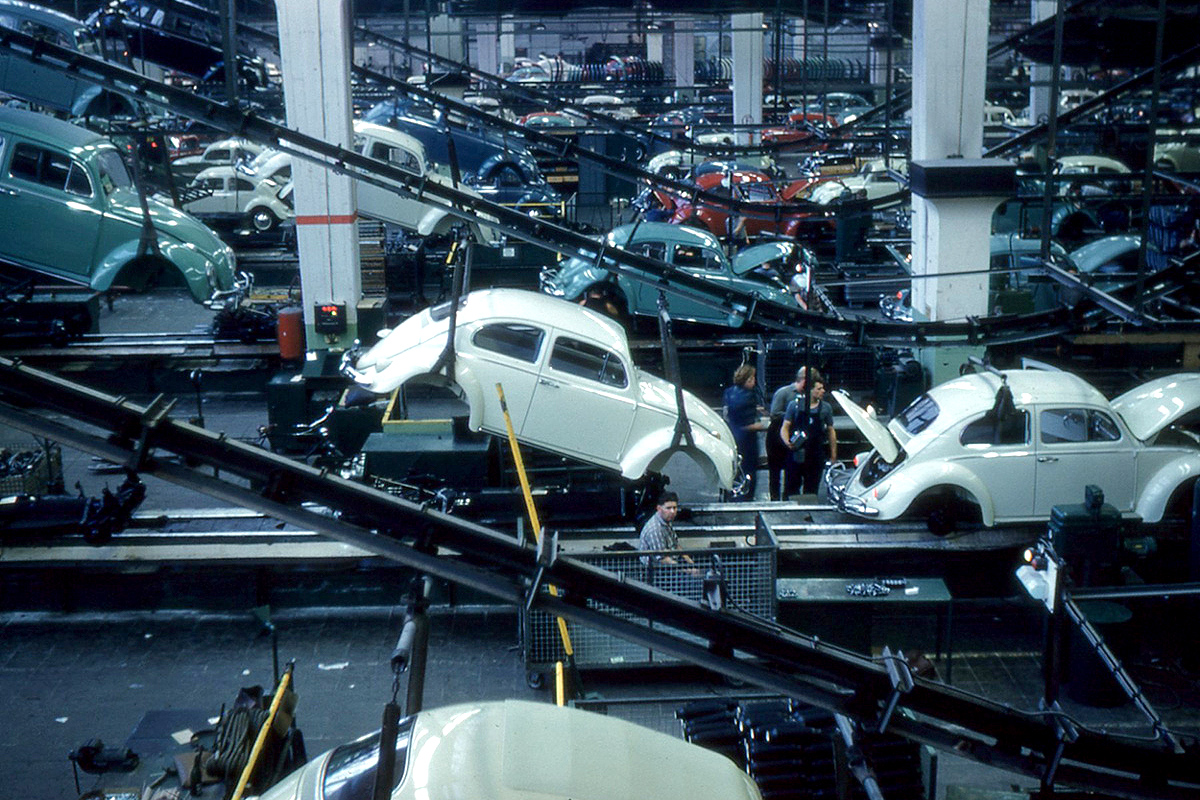

As health care delivery grew in scale and complexity, the system looked toward manufacturing processes as a template to improve efficiency while protecting quality. Six Sigma, process mapping and root cause analysis became standards in health care operations.

Physicians are increasingly familiar with fish bone graphs and value stream maps.

One area health care has been slower to adapt from manufacturing is standardization and decreased variation as a way to control quality. Clinical standardization was easier to embrace.

Standard order sets, care pathways, check lists and clinical decision-making algorithms are increasingly part of care delivery. To a lesser extent, utilization standardization in the form of appropriate use criteria has also been increasingly used.

One area that is still lagging is supply variations. Although supply chain management started to take an increasing role in health care, an effort to standardize supply and equipment has traditionally met significant resistance from providers.

Such effort is widely considered a major physician dissatisfier. The resistance against supply standardization generally centers on a few common themes:

- There are concerns that standardization will be tilted toward the lowest cost at the expense of quality. To address such concerns, value analysis teams were formed with significant physician representation and input. Their purpose is to identify the ideal spot at the intersection of cost efficiency and optimal quality.

For such committees to accomplish their goals, physician buy-in and engagement are key. Such efforts are becoming more common. Many institutions who were early adaptors to this approach have published their success stories. However, more progress is still needed. - There is concern that standardization will limit innovative care. Although innovation is paramount to progress in health care, the way new products are gaining the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval creates the need for further validation.

Multiple published studies highlighted the limitations of the approval process. A majority of new products are achieving their pre-market approval through noninferiority studies or minimal design modification to existing products. Often, post marketing surveillance is mandated to establish the safety profile.

Under those circumstances, weighing the value of early adoption against the benefit and cost efficiency is reasonable and at times prudent.

- There is lack of significant clinical studies linking supply standardization to quality improvement. Although this link is well established in manufacturing, its validity in health care needs to be explored further.

In summary, we do not need to start from scratch in order to tackle variation. Health care looked to manufacturing as a source of operation and quality improvement processes, and there is great potential to apply supply standardization principles that have had significant impact on the manufacturing industry to health care, specifically cardiology.

It is important to note that such potentials will need to be verified and optimized before being widely adopted. The evolution of supply management with clinical integration is a great early step.

The evolution of robust data analytics and the potential use of artificial intelligence will help validate the effect of decreasing supply variation on quality and efficiency.

We can also apply lessons learned from effectively managing STEMI patients to develop defined clinical strategies for atrial fibrillation and other complex patient populations.

Finally, we can borrow from principles of high reliability organizations, lean hospitals or other high performing programs and develop customized processes that work for our specific organizations.

In case you missed it, check out part 1 and part 2 of this article.