The Transition to Value – Mostly a Ripple, Will it Become a Wave?

Jan 19, 2018 | Larry Sobal, MBA, MHA, CMPE

You have probably heard the phrase “volume to value” a few hundred (if not a thousand) times. It has become such a common part of health care language that it is a wonder if we even stop to think about what it means anymore.

Discussions around shifting reimbursement models from fee-for-service (FFS) to value-based care have been going on for decades. Hospitals, physicians, politicians and others have long recognized the need to align payment methods to patient interests, and that paying for health care simply by the number of services provided has not improved care or reduced costs to anyone’s satisfaction. Indeed, for the past 40 years, U.S. spending on health care has been growing substantially faster than the economy, and it is estimated to reach nearly $5 trillion, or 20 percent of gross domestic product, by 2021. According to a recent Altarum report, overall health spending is up 30 percent since the 2007 recession.

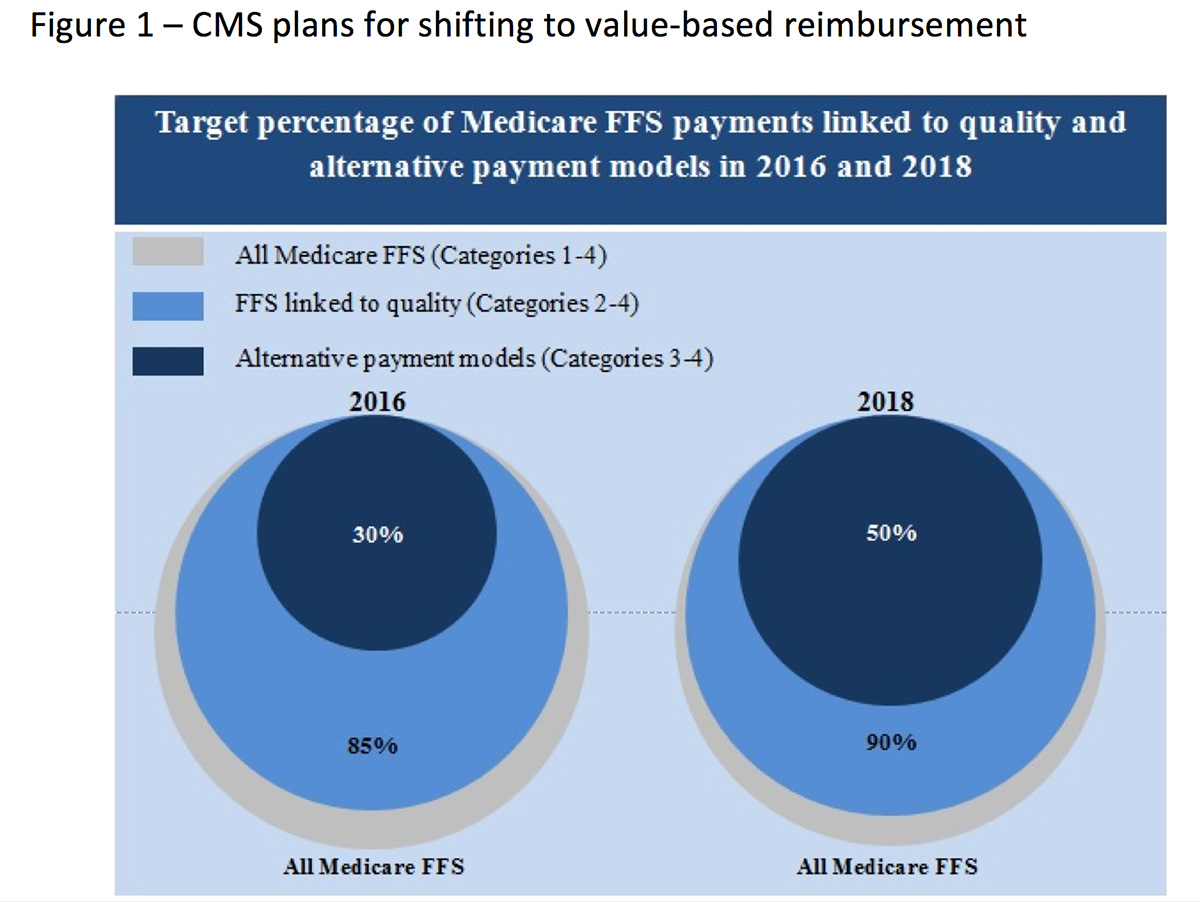

Thus, the idea of accountable care was born. In an effort to reduce costs and improve quality, the health care delivery system in the U.S. is described as undergoing a fundamental shift from volume to value. The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), along with various cost-controlling measures, continue to challenge health care providers to better manage and treat patients at a lower cost. One byproduct of the ACA has been the recent activity of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS has been busy releasing a series of initiatives as part of their stated goal of tying 30 percent of traditional, or FFS, Medicare payments to quality or value through alternative payment models (APMs) such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) or bundled payment arrangements by the end of 2016, and tying 50 percent of payments to these models by the end of 2018. This plan is illustrated in Figure 1.

For clarification, the three categories can be described as follows:

- All Medicare FFS – A reimbursement method in which doctors and other health care providers (including hospitals) are paid for each service performed. Examples of services include tests and office visits.

- FFS Linked to Quality – A reimbursement method in which doctors and other health care providers (including hospitals) are paid with a portion of the payment that varies based on the quality or efficiency of health care delivery.

- APMs – A reimbursement method in which some payment is linked to the effective management of a population or an episode of care. Payment is still triggered by delivery of services, but there are opportunities for shared savings or two-sided risk.

Starting with the election of President Trump, the direction of CMS has grown less certain, as evidenced by the appointment and subsequent resignation of HHS Secretary Tom Price. CMS Administrator Seema Verma signals that CMS, particularly Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), seeks a “new direction.” The nominee of the new HHS Secretary, Alex Azar, is expected to work closely with Verma on Medicare and Medicaid reform.

In this period of extreme uncertainty, history suggests that the degree of value-centric thinking and reengineering of the delivery of care will vary widely; for every program trying to focus on tighter attainment of clinical standards, improved patient experience or lowering costs, there are just as many (if not more) focused on volume growth.

This begs the question: is there really going to be a significant movement toward value (i.e. “a wave”), or is the U.S. just beginning to pay for health care differently and the transition will move slowly (i.e. “a ripple”)? Let’s explore both possibilities.

Defining Value

To make the argument that we are moving to greater value in health care, we have to first accept that the meaning of “value,” at least as it pertains to health care, is ambiguous.

The perspective on value appears to depend on who you ask. For example, a recent survey of 5,031 patients, 687 physicians and 538 employers across the nation not surprisingly found that while most people think health care must deliver "value," it is not clear what that definition means, or how they would prioritize the components of cost, service and quality.

For example, the survey showed that when asked to prioritize quality, cost or service as components of value:

- 88 percent of physicians ranked quality (defined as the efficiency, effectiveness, safety and outcomes) as the top priority, compared to 62 percent of patients and 20 percent of employers.

- 43 percent of employers ranked customer satisfaction or service as a top priority of value, compared to 12 percent of patients and 7 percent of physicians.

- 37 percent of employers said cost was a top component of value, followed by 26 percent of patients, and only 5 percent of physicians.

However, it is not that definitions of health care value are nonexistent, and the following examples are some notable interpretations. Michael Porter, a distinguished Harvard Professor and author, attempted to define value in his 2010 New England Journal of Medicine article as “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent.” Dartmouth defines value as “quality over cost over time.” The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research speaks of bringing together information on the quality of health care, including patient outcomes and health status, with data on the dollar outlays going towards health and focusing on managing the use of the health care system to reduce inappropriate care, while identifying and rewarding the best-performing providers. The ACC defines value in health care as “the best combination of quality and price.”

What evidence exists that we are seeing this form of greater value in health care? Unfortunately, demonstrating evidence-based, high-value health care remains one of the foremost challenges in health care today. Despite increasing scrutiny of the real-world effectiveness, safety and costs of medical care, we have not conclusively deepened our understanding of high-quality and high-value care, nor can we quantify it. The reality is that avoiding over treatment and over diagnosis are often easier said than done, and the hundreds of health care performance metrics being collected and reported on today do not point toward a clear and consistent record of continuous improvement, at least not across the U.S. health industry.

The U.S. population health measures, such as life expectancy and preterm birth, lag behind those of almost every other developed nation. Patients are still harmed by medical errors. Recent assessments indicate that 10 years after the Institute of Medicine report, To Err Is Human estimated that medical errors cause up to 98,000 deaths in hospitals each year, and roughly 15 percent of hospital patients are still being harmed during their stays. Care coordination places further strain on patients and the system, with an estimated 20 percent of discharged elderly patients returning to the hospital within 30 days.

Are there pockets of increasing value? Yes. However, the overwhelming evidence is that the U.S. health care system is not innovating and spreading improvements on a widespread enough basis to say that it is moving to better health care value as a whole.

Are Value-Based Payment Models Becoming the Norm?

Payors have been touting that the volume-to-value movement is imminent for some time now. In a 2017 article in Forbes, the following data was shared:

- UnitedHealth Group spends $52 of its $115 billion “in total medical spend” through value-based care.

- Over 45 percent of Aetna’s medical spend is currently running through some form of value-based care model.

- Anthem, which operates Blue Cross Blue Shield plans in 14 states, says it has 43 percent of payments tied to shared savings programs.

- Value revenue as a per cent of total practice revenue can be low. We are 1 percent, yet have SS/ACO with all payers and Medicare.

Generally, the reimbursement vehicles that are being categorized as “value-based” include the following (listed from low risk to high risk regarding how much risk hospitals and physicians assume):

- Pay for Coordination – Additional per capita payment based on the ability to manage care.

- Pay for Performance – Payments tied to objective measures of performance.

- Bundles (aka episodic payment) – Instead of paying separately for hospital, physician and other services, a payer bundles payment for services linked to a particular condition, reason for hospital stay and period of time.

- Shared savings – Generally calls for an organization to be paid using the traditional FFS model, but at the end of the year, total spending is compared with a target spend, usually involving better care coordination, decreased utilization, lower cost and disease management.

- Shared risk – In addition to sharing savings, if an organization spends more than the target, it must repay some of the difference as a penalty.

- Global capitation – An organization receives a per-person, per-month payment intended to pay for all individuals’ care, regardless of what services they use.

CMS has been the most active in developing and experimenting with value-based payment models. Those CMS payment models include the Accountable Care Organizations, Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), Next Generation ACO Model, Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease Care (CEC) Model and the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) Model.

According to CMS, the MSSP will have 561 ACOs participating in 2018, including 124 new entrants into the program, covering a total of 10.5 million assigned beneficiaries. The program overall has grown each year since its launch in 2012, when 220 ACOs covered 3.2 million beneficiaries. In 2017, 480 ACOs participated, covering nine million beneficiaries. As in past years, the vast majority of ACOs (82 percent overall) are in the upside-only Track 1 of the program, but the share of those taking on downside risk increased to the new risk-based Track 1+ model. Eighteen percent of all MSSP ACOs will be assuming risk in 2018, with 55 participating in Track 1+, eight in Track 2 and 38 in Track 3, all of which qualify as Advanced Alternative Payment Models under the Quality Payment Program introduced by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

Furthermore, CMS has just announced a new bundled payment model – Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Advanced. The new model is an advanced version of the (BPCI) program launched in 2013. It is voluntary and will cover 32 clinical episodes. The number of providers that will sign up by the March 12 deadline is unknown. However, participation does not mean just signing up, it also means staying in. Only 12 percent of hospitals eligible for the original BPCI chose to participate and nearly half of them dropped out, according to a JAMA report.

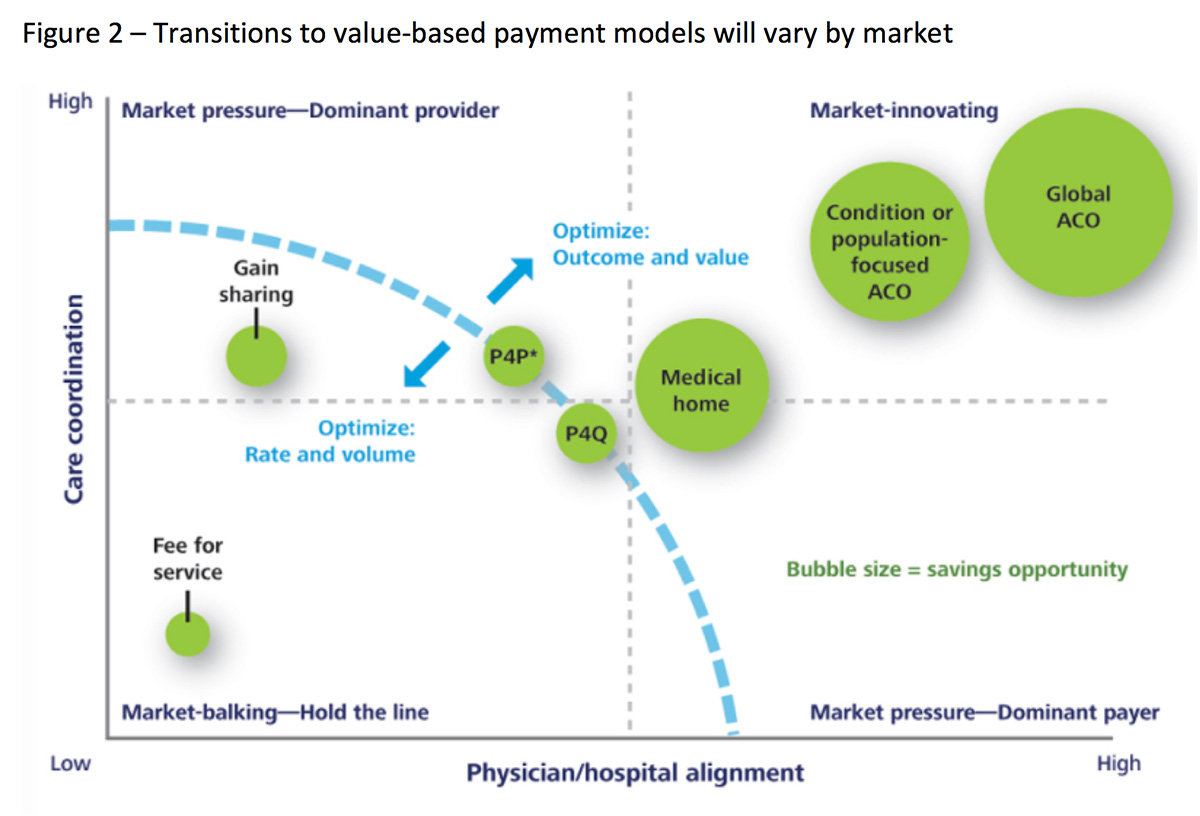

These facts would suggest that we may be nearing a tipping point where volume is truly being de-throned by value as organizations move down a continuum toward value-based reimbursement. However, health systems and especially physicians, continue to express a curious apprehension about reimbursement moving away from fee for service, as many claim it has not become much of a reality for them. Figure 2 suggests that the degree of adoption of value-based payment models will be very market specific, depending on local circumstances.

The Current Reality

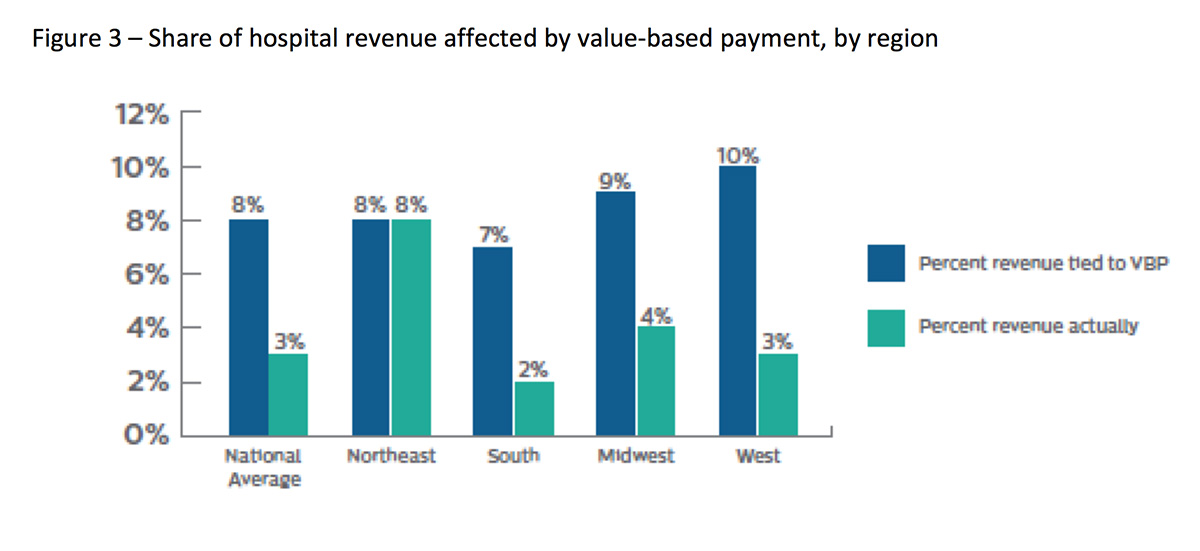

Despite the media hype and the overuse of the term “volume to value,” the actual data suggests that adoption of value-based reimbursement models is still in its infancy, with some markets described as being in adolescence.

A recent survey by Philips, and illustrated below in Figure 3, shows that exposure and impact of value-based payments remain limited, as less than 10 percent of revenues tie to value-based payment with the northeast U.S. having the highest utilization. Even so, the survey showed that less than one-third of hospitals participate in any value-based payment model.

What Matters Today

There are three things to pay attention to. First, whether you are an independent physician in an ACO, or an employed physician whose health system is in one of the Medicare APMs, the odds are you are still being paid on some derivative of FFS, with a high likelihood that work relative value units still drive most (if not all) of your individual compensation. This reason is because many organizations have not yet determined how to successfully align meaningful physician compensation with organizational reimbursement.

Second, despite their claims of having nearly 50 percent of their reimbursements in value-based models, commercial payers have been slow to move beyond FFS and are more prone to offer upside-only bonus incentive models versus more aggressive models, such as bundled payments or full or partial capitation that expose hospitals, and especially physicians, to real downside risk.

Third, the variety of value-based payment models are thus far not delivering financial rewards to the participating organizations. Some providers are investing in infrastructure to be ready for value-based care delivery models, but the large payoffs on any significant scale have not come yet to justify it in most instances. New technologies to improve care and patient access, such as telemedicine, cost money. Hospitals and health systems are also buying primary care and specialty medical groups, and refocusing their processes and protocols so they are not creating narrow networks-the payer is especially for MA and the individual exchange create narrow networks that serve defined populations. These are huge expenses that will continue to drain health system resources, and achieving real value under value-based models remains elusive for many that struggle to manage chronic patient populations and transitions into, and from, post-acute environments.

Reimbursement shifts are taking longer than expected and the initial investment in value-based infrastructure, combined with a reduction in revenues from removing unnecessary procedures and images, are having a detrimental effect on profits. With that in mind, it’s possible that value-based reimbursement models are not yet proving to be an attractive replacement for fee-for-service, at least when it comes to the bottom line. If that’s the case, it’s easy to see why some organizations may not be moving quickly away from their historical fee for service environment.

Conclusion

In summary, health care is moving towards something called value, but the value transformation is currently just a ripple and not a wave. For most hospitals and physicians, despite often having many contracts that might be described as "value-based", for the most part only a very small percentage of patients and reimbursement dollars are being paid in any form of a true risk-based model. Therefore, it becomes imperative that each organization reach their own consensus on the definition of value, where the market is heading, what position they want or need to be in their market and the most critical goals and strategies needed to fulfill the definition of a high-value performer. Focusing on these is the best chance to move further along on the volume-to-value continuum and doing so at the right place.

This article was authored by Larry Sobal, MBA, MHA, CMPE, Vice President Service Lines, Ascension Wisconsin.