Feature | Developing a Cardio-Oncology Program From an Early Career Perspective: Challenges Faced and Lessons Learned

The number of cancer survivors has increased in the last several decades due to rapid advances in therapy. Many of these patients are exposed to cardiotoxic regimens that can potentiate downstream cardiovascular risk, particularly on a background of shared medical and lifestyle risk factors for cardiac disease and cancer.

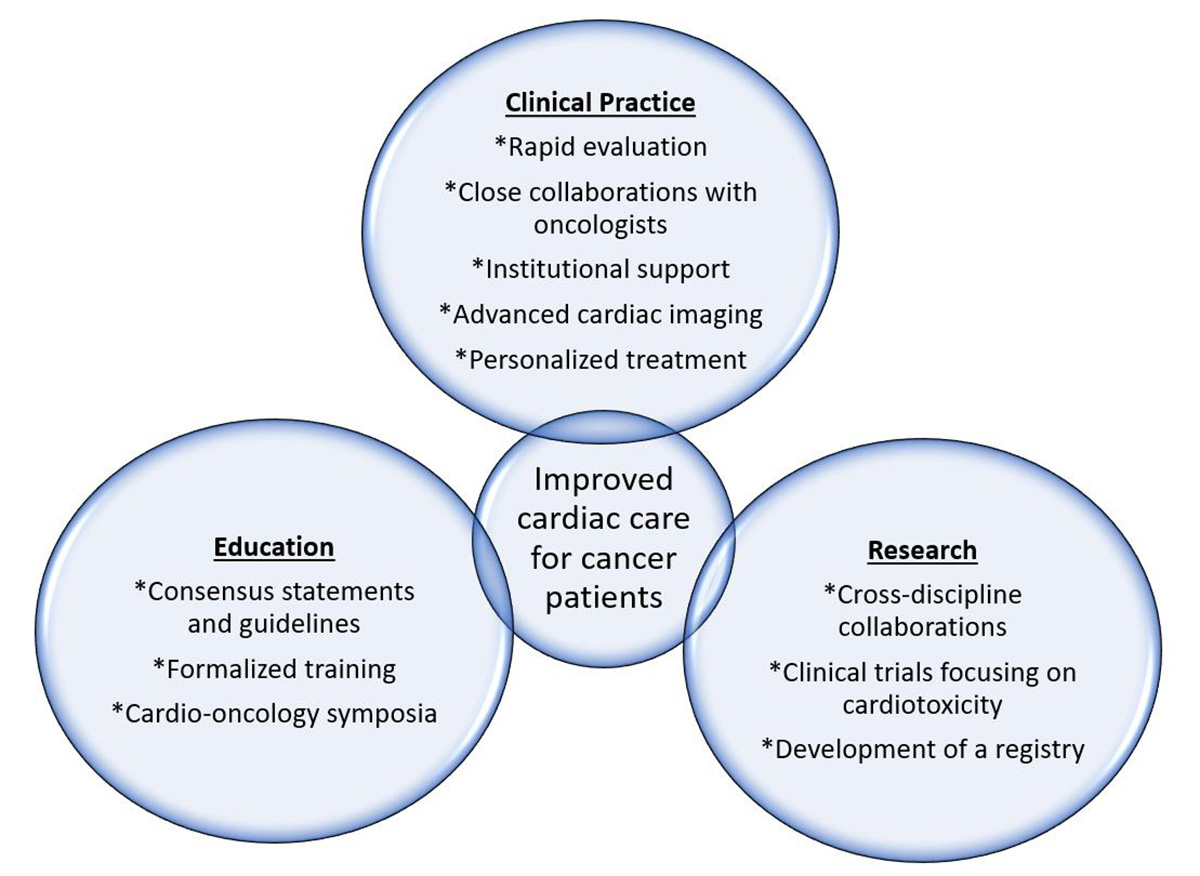

There is growing recognition of the magnitude of the problem, as cardio-oncology programs are being established at many centers across the U.S. and an escalating number of publications are dedicated to this topic. A “roadmap” for developing an effective cardio-oncology program was proposed by the ACC Cardio-Oncology Working group in 2015. In this article, we describe our experience establishing a cardio-oncology program at the University of Washington-Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA) as early career physicians.

Clinical Practice

A successful cardio-oncology program requires cooperation and cultural acceptance between oncology and cardiology. The ACC national cardio-oncology survey showed gaps in knowledge, with many cardiologists uncomfortable managing cardiac complications of chemotherapy and oncologists unsure whether and when to refer their patients to cardiology. While establishing our cardio-oncology program, we focused on building robust foundational relationships with our oncology colleagues. We established awareness for cardio-oncology both within our cardiology division and the different oncology subgroups through:

- Formal and repeated educational sessions for both oncologists and cardiologists through dedicated didactic series, literature review and cancer network events.

- Constant and up-to-date feedback to providers on cardiac management. We have an open line of communication via direct phone and electronic communication with oncologists and advance practice registered nurse providers for new referrals, changes in cardiac status or significant changes in medications or chemotherapy regimens for patients we co-manage.

- Ongoing input for patients receiving potentially cardiotoxic chemotherapy. We provide constant availability to the oncology services and our cardiology colleagues for recommendations on management of high-risk cardiac patients receiving chemotherapy and patients with potential cardiotoxicity.

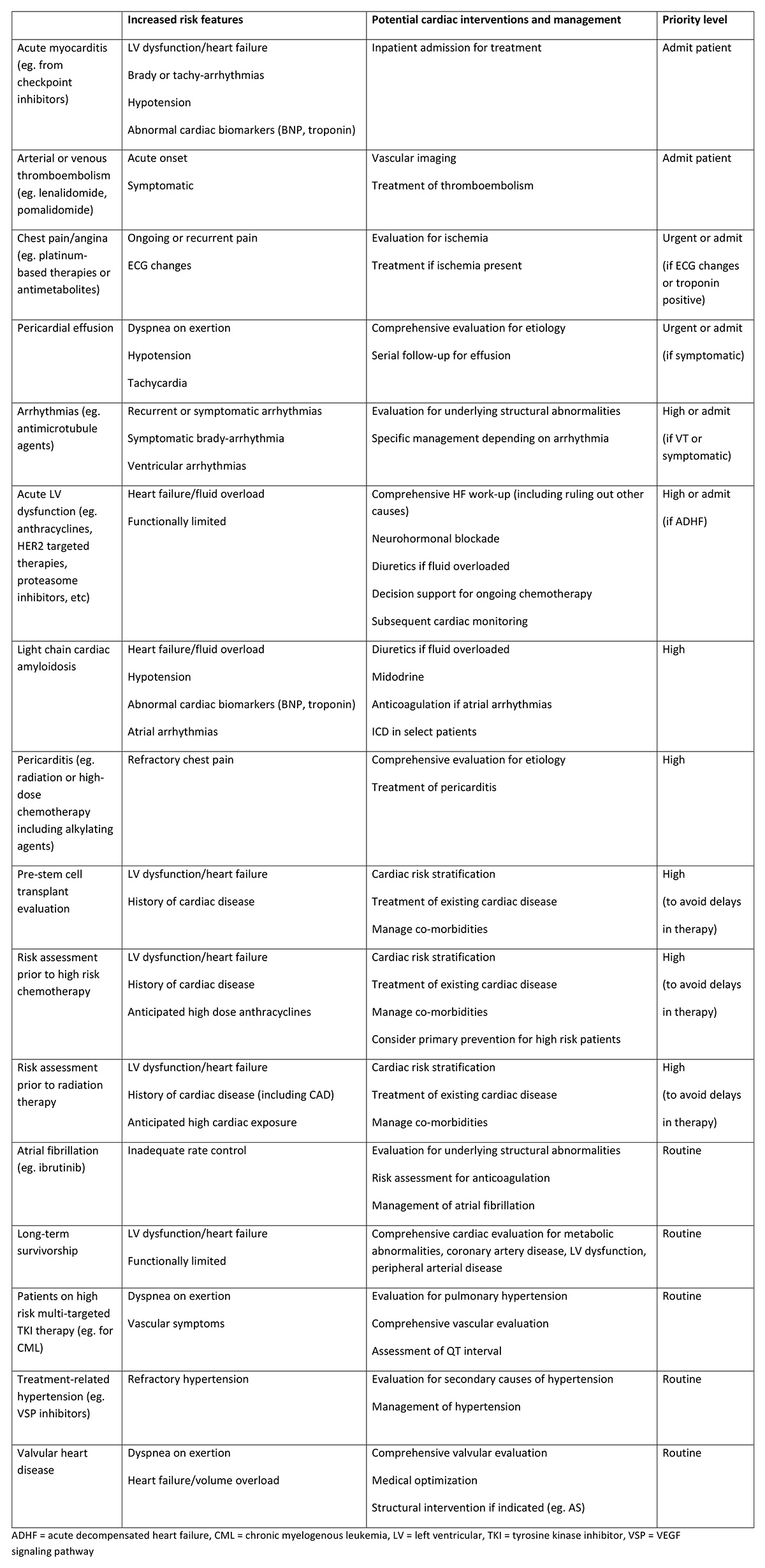

From a practical standpoint, we emphasized the need for rapid cardiac evaluation of these patients to avoid delays in chemotherapy or bone marrow transplant. As a burgeoning program, we lacked enough providers to see all patients at all times, and developed methods to prioritize the highest risk patients. These included patients that needed cardiac evaluation prior to treatment, were sicker overall and patients with substantial cardiac dysfunction or active cardiac problems that might limit additional treatment options. We have a dedicated clinic nurse navigator that triages referrals and classifies them based on urgency. (Table)

As providers, we quickly realized that widely encompassing paradigms do not apply. Unlike the use of neurohormonal blockade in left ventricular systolic dysfunction, most cardio-oncology patients cannot be grouped and treated together as a single disease state. Each individual case requires attention to balancing the risk of cancer with risk of cardiotoxicity and understanding the underlying mechanisms of the specific chemotherapy regimen. In this era of personalized medicine in oncology, personalized treatment is necessary from cardiology.

Institutional support is critical for success of any program, and we were able to actively foster support through demonstration of benefit from both a patient-centric clinical model and overall fiscal viewpoint. In pursuing this, we achieved high levels of patient and referrer satisfaction with a value-based model of care that consolidated clinic visits between cardiology and oncology temporally with imaging and ancillary services. Displaying a rapid growth of referrals and increases in appropriate use of cardiac imaging and other cardiac procedures was also essential to fostering administrator support of the program and justification for dedicated support staff.

Cardiac imaging plays a crucial role in cardio-oncology for baseline screening and serial surveillance in patients receiving cardiotoxic regimens. Immediate access to echocardiography is imperative to avoid delays in treatment. We met this need by dedicating echo timeslots specifically for cancer patients and opened up weekend days allocated to these patients. We are currently in discussions about having a separate echo imaging site at the cancer center to further expedite and streamline access. Although we do not routinely perform 3D measurements and strain imaging on all echo studies, we created a specific protocol to obtain these parameters for cancer patients based on recent guidelines.

Education and Knowledge

One of the challenges we faced as early career providers was locating mentorship specific to cardio-oncology, given the relative newness of the field and evolving practice standards. We were fortunate to receive support from cardio-oncology experts from other institutions eager to provide ongoing guidance from a cardiac standpoint, while developing institutional mentorship by established oncologists at the SCCA.

Despite the increased awareness and recognition of cardio-oncology as a discipline, formalized guidelines and statements for management of these complex patients are still being developed. There are a number of clinically focused consensus statements or practice guidelines in cardio-oncology that serve as educational backbones for providers seeking to create a cardio-oncology program:

- ASCO – Prevention and Monitoring of Cardiac Dysfunction in Survivors of Adult Cancers

- ASE/EACI – Multimodality Imaging Evaluation of Adult Patients During and After Cancer Therapy

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society – Evaluation and Management of Cardiovascular Complications of Cancer Therapy

- Circulation: HF – Cancer Therapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction and Heart Failure

- ESC Position Paper on Cancer Treatments and Cardiovascular Toxicity9

- JACC – Best Practices in Cardio-oncology

- NCCN – Survivorship Clinical Practice Guidelines

- SCAI – Evaluation, Management, and Special Considerations of Cardio-oncology Patients in the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory

There are currently no formalized curricula for a dedicated fellowship in cardio-oncology, although there was a recent proposal from the International Cardio-Oncology Society and Canadian Cardiac Oncology Network for essential components of contemporary training in cardio-oncology. The ACC Cardio-Oncology Section has called for creation of milestones that would serve as the foundation for integration of cardio-oncology specific training into cardiovascular fellowship training core curriculum.

There are several national symposia that we found particularly helpful in keeping up-to-date with the latest knowledge in cardio-oncology and for networking with other specialists in the field:

- ACC Advancing Cardiovascular Care of the Oncology Patient

- Global Cardio-Oncology Summit

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cardio-Oncology Symposium

Research

Research in cardio-oncology requires a close collaboration between cardiology and oncology providers, as understanding nuances of cardiac complications and mechanisms of cardiac injury are equally necessary. By establishing strong clinical and educational relationships with our oncology colleagues, it has naturally led to opportunities for clinical and translational research.

Most of the available data in the literature are single center studies or secondary analyses of oncology clinical trials. There has been growing interest and an increasing number of clinical trials specifically addressing primary prevention or secondary treatment of cardiotoxicity, but research in cardiotoxicity remains sparse compared to other sub-disciplines in cardiology such as heart failure. In Europe, the European Society of Cardiology created the Cardiac Oncology Toxicity Registry to capture cardiotoxicity in breast cancer treatment across numerous institutions. However, we still lack a multi-institutional registry in the U.S. for cardiotoxicity or one that is more encompassing of the expansive cardiac complications that can occur with treatment, including cardiac risks accrued from expanding usage of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and checkpoint inhibitors.

In summary, our journey in establishing a cardio-oncology program at UW/SCCA has been very educational and led to clinical and research collaborations with oncology that continue to grow. Our program was fortunate to not only have institutional support, but enthusiastic external mentorship from leaders in the field from other centers and we remain passionate to give back by sharing our knowledge and dedication to training and education with the broader community. These are exciting times and ongoing collaborations between cardiologists and oncologists across institutions will no doubt lead to further advances in the field.

This article was authored by Richard K. Cheng, MD, FACC, from the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, WA; S. Carolina Masri, MD, from the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, WA; and Ana Barac, MD, PhD, FACC, from MedStar Heart and Vascular Institute in Washington, DC.