Convulsion Confusion in a Child

A 9-year-old boy with a 2-year history of seizures presents to the emergency department (ED) after another seizure. The event occurred while he was playing soccer on the school playground. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was administered, and he recovered without requiring cardioversion or medications.

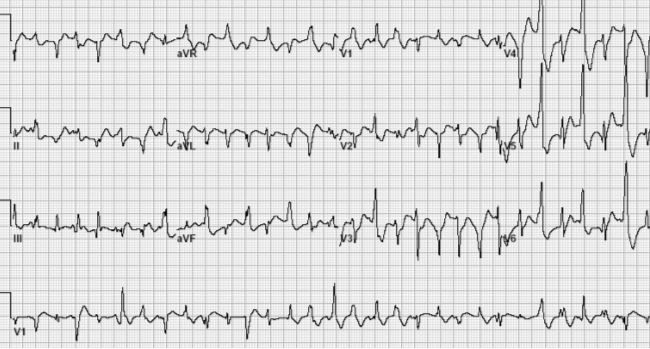

In the ED, he undergoes an electrocardiogram (ECG) (Image 1). His physical examination findings, echocardiogram findings, and laboratory study values are all unremarkable. He does not have dysmorphisms. His only medication is levetiracetam to treat his seizure disorder.

Image 1

Given this clinical presentation, which one of the following is the most likely mechanism for the observed arrhythmia?

Show Answer

The correct answer is: C. Cardiac calcium dysregulation.

The ECG (Image 1) had findings of bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (VT), a rare but distinct arrhythmia with a limited differential diagnosis that includes Andersen-Tawil syndrome (ATS), digitalis toxicity, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). Bidirectional VT occurring in the context of exertional syncope is most indicative of CPVT. Bidirectional VT is an uncommon type of VT in which there is a 180-degree change in the QRS axis during the VT event. As shown in this ECG tracing, this is a wide QRS tachycardia with varying QRS morphologies (best seen in lead V1). Some of the VT beats have a QRS morphology consistent with a right bundle branch block and some with a left bundle branch block. This genetic arrhythmia syndrome is known for causing arrhythmias that can lead to syncope or sudden death in the setting of adrenergic stimuli, such as exercise, emotional stress, or excitement.1 All gene variants implicated in CPVT lead to cardiac calcium dysregulation.2 The classic (typical) form of CPVT is associated with a gain-of-function mutation in the ryanodine receptor (RYR2) gene, which encodes the ryanodine receptor (RYR2).

Although the differential diagnosis included ATS, this patient demonstrated none of the other features of this condition, including facial dysmorphisms, periodic paralysis, and clinodactyly. Digitalis toxicity, another differential diagnosis, was excluded because he was not taking digitalis. However, considering the possibility of a medication error or accidental ingestion would be important. For example, if digoxin had been mistakenly dispensed by the pharmacy instead of levetiracetam, or if another family member had been prescribed digoxin and the child accidentally ingested it, digitalis toxicity could explain this presentation. In such cases, obtaining a detailed medication history, examining the pills, and measuring a digoxin level, if available, would be critical steps to rule out or confirm this etiology.

The ECG findings were inconsistent with re-entry due to a bypass tract because of the irregularity in both the rate and QRS morphology. An automatic atrial tachycardia (AT) may have some wide QRS complexes due to aberrant conduction, but it is unlikely that all beats will be wide and present as a wide complex tachycardia. AT is also an uncommon cause of syncope. An example of re-entry through the His-Purkinje system would include idiopathic fascicular VT. This arrhythmia typically occurs in structurally normal hearts. It presents as a monomorphic VT with a QRS duration that is shorter and narrower compared with other VTs.

As illustrated in this clinical vignette, patients with CPVT are often misdiagnosed with a seizure disorder when the true underlying cause is an arrhythmia. Consequently, there is frequently a several-year delay between the onset of symptoms and the correct diagnosis.3 This arrhythmia can often be reproduced during an exercise test and can be confirmed with genetic testing. Genes associated with CPVT involve calcium handling in the myocyte, with the RYR2 gene most commonly involved.

Nonselective beta-blockers such as nadolol are first-line therapy for CPVT. More recently, flecainide, a sodium channel blocker and RYR2 inhibitor, has emerged as a significant adjunct treatment because of its effectiveness in suppressing and controlling ventricular arrhythmias.4 Left cardiac sympathetic denervation is another important adjunctive therapeutic option for patients who either do not tolerate medical management or continue to experience breakthrough arrhythmias despite optimized medical management. In managing CPVT, avoiding implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) placement is preferred because inappropriate or even appropriate shocks can lead to adrenergic stimulation and trigger a VT storm.5 Nevertheless, ICD placement may be necessary for select patients who continue to experience syncope or persistent VT after exhausting other medical and procedural treatment options.

This patient was initially started on nadolol (1 mg/kg/day), which he tolerated well. His resting rhythm after initiating nadolol was sinus with occasional premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). However, provocative exercise testing revealed bidirectional PVCs and episodes of nonsustained VT. Flecainide was added at 100 mg/m2/day and titrated until follow-up exercise testing showed only rare, isolated PVCs (120 mg/m2/day). For long-term rhythm surveillance of treatment efficacy, an implantable loop recorder was placed. Levetiracetam was discontinued. Over the following 3 years of follow-up, he remained free of symptoms, with no further episodes of seizure, syncope, or VT.

References

- Leenhardt A, Lucet V, Denjoy I, Grau F, Ngoc DD, Coumel P. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children. A 7-year follow-up of 21 patients. Circulation 1995;91:1512-9.

- Napolitano C, Mazzanti A, Bloise R, Priori SG. Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, eds. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; 2022. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1289/. Accessed 02/04/2025.

- Roston TM, Vinocur JM, Maginot KR, et al. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children: analysis of therapeutic strategies and outcomes from an international multicenter registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:633-42.

- Kannankeril PJ, Moore JP, Cerrone M, et al. Efficacy of flecainide in the treatment of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:759-66.

- Roston TM, Jones K, Hawkins NM, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: a systematic review. Heart Rhythm 2018;15:1791-9.