This patient's clinical presentation was suggestive of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA) rather than of myocarditis, yet the diagnosis remained uncertain. MINOCA represents true ischemic myocardial infarction (MI) and should be differentiated from nonischemic causes of myocardial injury, such as myocarditis and takotsubo syndrome. The most common causes of MINOCA are plaque disruption, coronary vasomotor dysfunction, and prothrombotic/embolic disorders. Importantly, missed obstructive CAD or spontaneous coronary artery dissection of distal segments or small branches could also be the cause, so it is paramount to review the angiogram in detail and have a low threshold for the use of intracoronary imaging if there are uncertainties.

At this point, a definitive diagnosis would require further investigation with CMR. Guidelines recommend CMR (Class 2a) for the evaluation of high-risk, troponin-positive patients with acute chest pain in whom obstructive CAD has been excluded to evaluate for MINOCA and differentiate it from alternative diagnoses. CMR is not routinely indicated for MI diagnosis if the clinical presentation is typical. Beyond securing a diagnosis of MINOCA, CMR may inform the underlying cause of MINOCA (e.g., embolic MI), guiding appropriate management and prognosis (Image 2).1

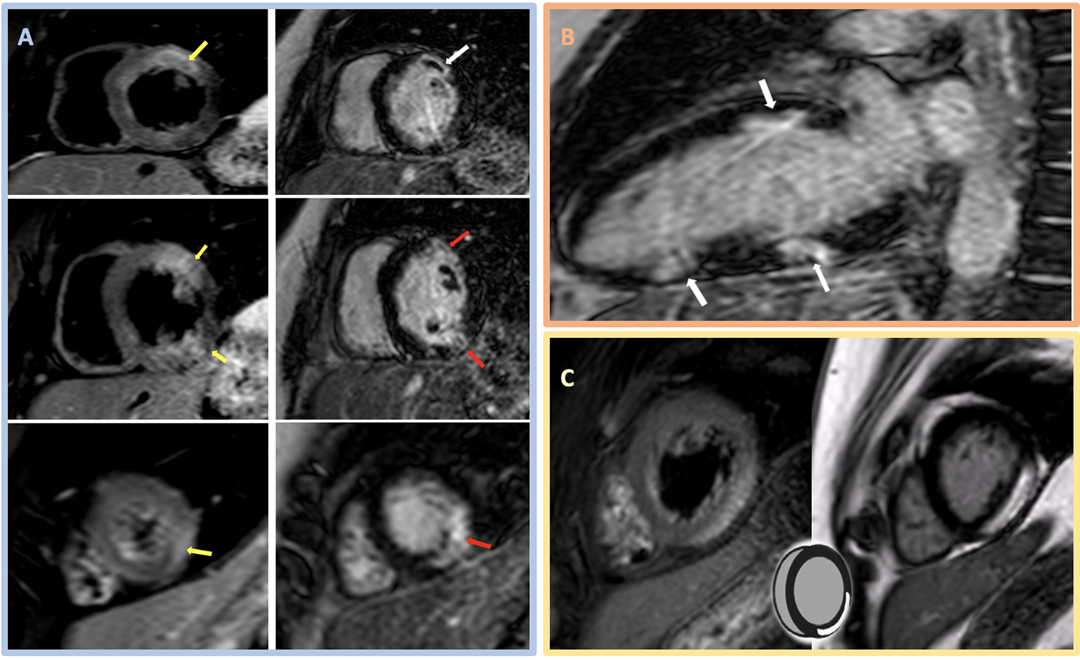

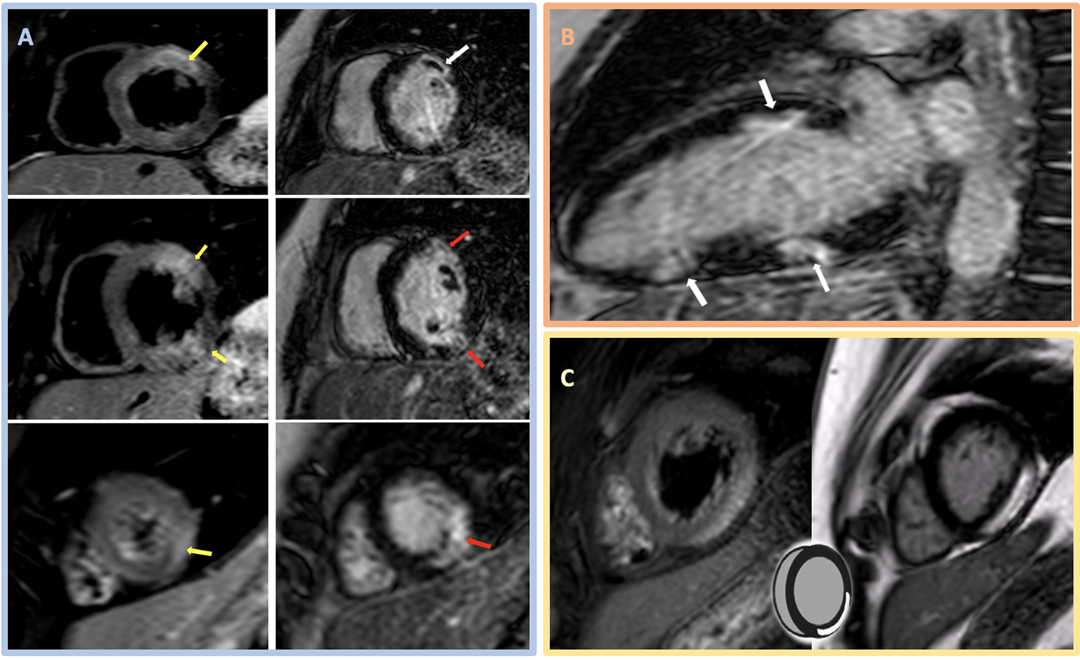

Image 2: CMR Images Showing Regional Myocardial Edema, LGE, MVO, and Myocarditis

Image 2: CMR Images Showing Regional Myocardial Edema, LGE, MVO, and Myocarditis. Courtesy of Miranda J, Lorenzatti D, Schenone A, Slipczuk L.

Image 2: CMR Images Showing Regional Myocardial Edema, LGE, MVO, and Myocarditis. Courtesy of Miranda J, Lorenzatti D, Schenone A, Slipczuk L.

(Panel A) CMR images in the SAX orientation (base-mid-apical) with T2-weighted images demonstrating regional myocardial edema (yellow arrow) on the left and the corresponding LGE (red arrow) and MVO depicted as a central dark core inside the bright scarred area (white arrow) on the right; these findings suggest acute/subacute MI. (Panel B) CMR LGE (white arrow) in a 2Ch orientation. (Panel C) Example of the classic appearance of myocarditis by CMR.

2Ch = two-chamber; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; MI = myocardial infarction; MVO = microvascular obstruction; SAX = short-axis.

In this case, CMR had findings of normal BiV size with preserved BiV function (LVEF 56% and right ventricular ejection fraction 54%). Tissue characterization revealed areas of myocardial edema (hyperintensity on T2-weighted images; panel A in Image 2) and subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in a multifocal distribution along the anterior midventricular segment, inferior midventricular segment, inferior apical segment, and lateral apical segment. Microvascular obstruction (dark area within the core of LGE uptake) was also evident, predominantly in the anterior segments (panels A and B in Image 2). These findings are consistent with MINOCA, with coronary embolism as the most plausible mechanism in the setting of APS. Hence, the importance of managing underlying connective tissue disorder and avoiding or minimizing anticoagulation interruptions was emphasized. The patient was discharged on apixaban and did not have any further events on follow-up.

Although chest discomfort with pleuritic features, lack of definitive ECG ischemic changes, and underlying connective tissue disorder would raise the possibility of myopericarditis, available evidence is insufficient to secure such diagnoses and initiate treatment. CMR is useful when suspecting myocarditis or any other MINOCA mimics. Myocarditis CMR features include a nonischemic injury with LGE that affects epicardial or midmyocardial regions (sparing the subendocardium) and does not follow vascular territories (panel C in Image 2).2,3

Whereas MINOCA remains a leading differential diagnosis, definitive diagnosis and targeted treatment require further investigation. Identifying the underlying cause of MINOCA is crucial, as it guides specific therapy (e.g., coronary thromboembolism requires anticoagulation therapy, plaque rupture is usually treated with antiplatelet agents and statins, vasospasm is managed with nitrates or calcium channel blockers). Secondary atherothrombotic prevention measures should be considered depending on the etiology.3,4

No further evaluation or treatment would be inappropriate. If left untreated, patients with MINOCA are at an increased risk of recurrent events. Approximately 25% of patients with MINOCA will experience angina in the subsequent 12 months.4

This case underscores the value of CMR in differentiating MINOCA from myocarditis (and other mimics). Although not always necessary for diagnosing MI, CMR can be invaluable when the diagnosis remains uncertain, as it helps secure a definitive diagnosis, inform possible mechanisms, and guide effective treatment. Recent evidence suggests that a CMR-first approach (i.e., before coronary angiogram) could change the presumed diagnosis of NSTEMI in up to 67% of patients and, in confirmed cases, identify a different infarct-related artery in 11% of patients.5

References

- Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al.; Writing Committee Members. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:e187-e285.

- Gudenkauf B, Hays AG, Tamis-Holland J, et al. Role of multimodality imaging in the assessment of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries: beyond conventional coronary angiography. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;11:[ePub ahead of print].

- Parwani P, Kang N, Safaeipour M, et al. Contemporary diagnosis and management of patients with MINOCA. Curr Cardiol Rep 2023;25:561-70.

- Tamis-Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, et al.; American Heart Association Interventional Cardiovascular Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Contemporary diagnosis and management of patients with myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e891-e908.

- Shanmuganathan M, Nikolaidou C, Burrage MK, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance before invasive coronary angiography in suspected non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2024;Jun 4:[ePub ahead of print].