A 51-year-old Caucasian man was transferred to the emergency department from a nearby non-interventional hospital with a diagnosis of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The patient was complaining of resting central chest pain for 2 hours prior to admission, but upon arrival, he was pain free. His electrocardiogram showed mild ST-segment depression in the anterior precordial leads. His initial troponin I was elevated at 147 ng/L (normal value <5 ng/L). A two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular function. The patient was a smoker and had a history of hypertension. There was no history of diabetes or family history of coronary artery disease. Body mass index was 28 kg/m2.

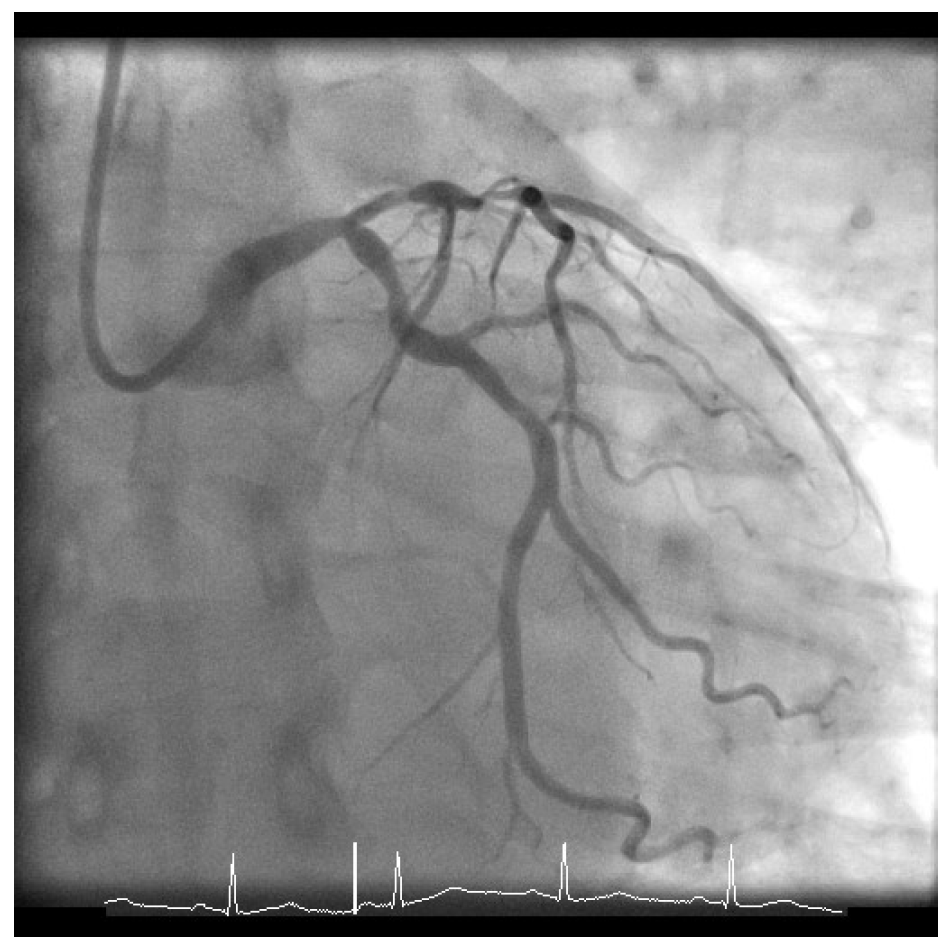

Given his presentation, the patient underwent an urgent coronary angiogram, which revealed a 50-60% stenosis of the distal left main (LM), 80% stenosis of the ostium of the left anterior descending coronary artery with 90% stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, 60-70% proximal left circumflex stenosis (Figure 1), and mild atheroma of the right dominant coronary artery (Figure 2). His calculated SYNTAX score was 24, and the case was formally discussed in the multidisciplinary team meeting with cardiac surgeons and cardiologists.

Figure 1: Left Coronary Artery

Figure 2: Right Coronary Artery

The correct answer is: C. The data suggest equipoise between contemporary PCI and CABG; this should be discussed with the patient

The current data and guidelines on LM disease address several aspects of the case, and they need to be considered by the multidisciplinary team.1 Results of studies comparing PCI using drug-eluting stents with CABG in these patients suggest non-inferiority of PCI to CABG for the safety composite of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke even after 5 years of follow-up.2 However, there are individual criteria that could be used to prefer one revascularisation strategy over than another. Based on recent guidelines,1 the primary discriminatory criterion would be the SYNTAX score. Specifically, patients with low SYNTAX score (<22) would be good candidates for either treatment (Class I, Level of Evidence A). On the contrary, in patients with more complex anatomy (SYNTAX score >33), CABG should be preferred over PCI (Class III, Level of Evidence B). Finally, the intermediate group (SYNTAX = 22-33) is more likely to benefit from CABG, but PCI should be considered as a possible alternative (Class IIa, Level of Evidence A).

Apart from the overall angiographic characteristics, both the local LM bifurcation characteristics should be incorporated in the evaluation. Characteristics that would increase the complexity and challenge of PCI to LM follow:

- A short LM with the main branch originating almost directly from the aorta

- An angulated side branch or T-shaped bifurcation angle

- Large, tapered calibre of the main vessel

- Co-existence of a large ramus (approximately in 10% of cases)

- Large territory at jeopardy for the left circumflex especially when it is a co-dominant circulation (about 15% of cases), thus the LM would supply all or nearly all left ventricle myocardium3

Furthermore, several clinical and technical aspects should be incorporated into decision-making in these cases, with the primary goal of accomplishing complete revascularisation.1,3 More contemporary studies have tried to optimize PCI-related revascularisation by using more sophisticated risk stratification tools such as the SYNTAX II score, which integrates clinical (age, sex, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral arterial disease), laboratory (creatinine clearance), imaging (left ventricular ejection fraction), and angiographic characteristics. Although LM disease was an exclusion in the SYNTAX (Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) II trial, the principle of using non-angiographic parameters to facilitate decision-making is noteworthy. Furthermore, the use of technological advancements such as intracoronary imaging (intravascular ultrasound [IVUS] or optical coherence tomography), physiological guidance (fractional flow reserve), and newer, more potent antiplatelet agents (such as ticagrelor and prasugrel) has already shown improved results in LM revascularisation with PCI.4

Notably, despite using 10-year-old technique in the SYNTAXES (Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery Extended Survival) study, CABG provided similar survival compared with PCI.5 No difference between the 2 groups was evident in patients with LM disease (26% vs. 28%, respectively; hazard ratio 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.68-1.20; p = 0.47). Furthermore, there was no association between the SYNTAX score and 10-year all-cause mortality, confirming that SYNTAX score has some limitations as a prognostic tool.6 In fact, several changes have been introduced over time to refine the SYNTAX score's prognostic ability. As mentioned, the SYNTAX II score, although not extensively investigated for its role in decision-making for LM disease, attains reasonable discrimination for short-term mortality after PCI or CABG.6

A significant interaction with time is notable, providing early benefit for PCI in terms of myocardial infarction and peri-interventional stroke, which is subsequently offset by a higher risk of spontaneous myocardial infarction during long-term follow-up. The need for repeat revascularisation is higher with PCI than with CABG. In order to reduce the risk of future revascularization, the use of IVUS is particularly helpful in the determination of plaque extent and characteristics within the LM, as well as in determining ostial involvement of daughter branches. IVUS can provide an estimate of the ischemic burden of the LM lesion, and its use following LM PCI improves clinical outcomes.7 Many studies have shown that the disagreement between IVUS cut-off (minimal luminal area [MLA] of ≥6 mm2) and angiographic criteria for defining a significant stenosis is substantial.7,8 In the prospective multicenter LITRO (Spanish Working Group on Interventional Cardiology) study, more than 4 out of 10 of patients with significant angiographic LM stenosis (≥50%) had a prognostically safe MLA of ≥6 mm2, whereas 1 out of 3 with a non-significant angiographic stenosis of <30% had a significant reduction of residual lumen (MLA of <6 mm2).9 In addition, IVUS provides many other benefits that assist on LM PCI. IVUS can help in the treatment plan, especially in calcified lesions, in sizing of stents, and in the optimization of stent placement because it can confirm adequate expansion and apposition of stents. These benefits translate into further improvement in clinical events, especially in patients treated with a two-stent strategy and patients with distal LM lesions.

In conclusion, although CABG was historically uniformly advised for patients with LM disease, recent studies have shown non-inferiority of contemporary LM PCI, especially when it is IVUS-guided and performed in expert centers. In these cases, discussing both choices with the patient seems the best solution. Therefore, answers A, B, and D are incorrect, and answer C is the most appropriate answer based on current knowledge. Finally, it is crucial to bear in mind that the person who ultimately makes the final informed choice is the patient. It has been well-described that even if the physician believes that the best solution is CABG, and even if during the consultation CABG is favored, more than half patients may disregard this advice and eventually select PCI.10 The SYNTAXES trial confirms that careful PCI in a trial setting is a reliable and safe long-term alternative for patients with LM disease, and it provides survival results comparable to CABG.5

References

- Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J 2019;40:87-165.

- Head SJ, Milojevic M, Daemen J, et al. Mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting for coronary artery disease: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet 2018;391:939-48.

- Fajadet J, Capodanno D, Stone GW. Management of left main disease: an update. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1454-66.

- Serruys PW, Kogame N, Katagiri Y, et al. Clinical outcomes of state-of-the-art percutaneous coronary revascularisation in patients with three-vessel disease: two-year follow-up of the SYNTAX II study. EuroIntervention 2019;15:e244-e252.

- Thuijs DJFM, Kappetein AP, Serruys PW, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease: 10-year follow-up of the multicentre randomised controlled SYNTAX trial. Lancet 2019;394:1325-34.

- Farooq V, van Klaveren D, Steyerberg EW, et al. Anatomical and clinical characteristics to guide decision making between coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for individual patients: development and validation of SYNTAX score II. Lancet 2013;381:639-50.

- de la Torre Hernandez JM, Baz Alonso JA, Gómez Hospital JA, et al. Clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance in drug-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary disease: pooled analysis at the patient-level of 4 registries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:244-54.

- Kassimis G, de Maria GL, Patel N, et al. Assessing the left main stem in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. What is "significant"? Function, imaging or both? Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2018;19:51-6.

- de la Torre Hernandez JM, Hernández Hernandez F, Alfonso F, et al. Prospective application of pre-defined intravascular ultrasound criteria for assessment of intermediate left main coronary artery lesions results from the multicenter LITRO study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:351-8.

- Kim C, Hong SJ, Ahn CM, et al. Patient-Centered Decision-Making of Revascularization Strategy for Left Main or Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease. Am J Cardiol 2018;122:2005-13.