A 57-year-old woman with a past medical history relevant for hypertension, obesity (BMI 32 kg/m2), tobacco abuse (20 pack years) and left hip osteoarthritis was admitted for a large asymptomatic pericardial effusion.

The patient was scheduled to have a hip replacement for osteoarthritis and pre-operative testing revealed she had low voltage on the preoperative electrocardiogram (EKG) (Figure 1) and a "water bottle sign" on chest X ray (Figure 2). An echocardiogram was also performed which showed a posterior pericardial effusion adjacent to the left ventricle measuring 1.3 cm and anterior pericardial effusion adjacent to the right ventricle measuring 2.5 cm (Figures 3 and 4). The inferior vena cava was dilated at 2.7 cm, but compressibility could not be assessed due to suboptimal subcostal images. However, there were no other signs of tamponade. Specifically, there was no overt chamber collapse, and respiratory inflow variation across the mitral valve was 17.6% and across the tricuspid valve was 54%.

Based on these findings, she was sent to the emergency department for further evaluation and management. The patient denied any chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, recent trauma, thoracic radiation, recent cardiac intervention, personal history of cancer or autoimmune diseases but reported 60-pound weight gain in the preceding 5 months. She was not very active recently due to her left hip pain and she spent most of the day in a wheelchair. Her temperature was 37 degrees Celsius, pulse was 78 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 18 breaths per minute and blood pressure was 136/85 mmHg. Her physical exam showed obesity, point of maximal impulse could not be palpated, regular heart rate and rhythm, normal S1 and S2 without a pericardial rub and no jugular venous distention, pulsus paradoxus, lower limb edema, thyromegaly or thyroid mass.

She had normal kidney function, negative cardiac enzymes, hemoglobin of 15.1 g/dL (normal range: 11.5 - 15.5 g/dL), platelets of 405 k/uL (normal range: 150 - 400 k/uL), international normalized ratio of 1.0 (normal range: 0.8 - 1.2), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 27 mm/hour (normal range: 0 - 20 mm/hour), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) of 104 uU/mL (normal range: 0.400 - 5.500 uU/mL) and a free thyroxine (T4) of 0.2 ng/dL (normal range: 0.9 - 1.7 ng/dL).

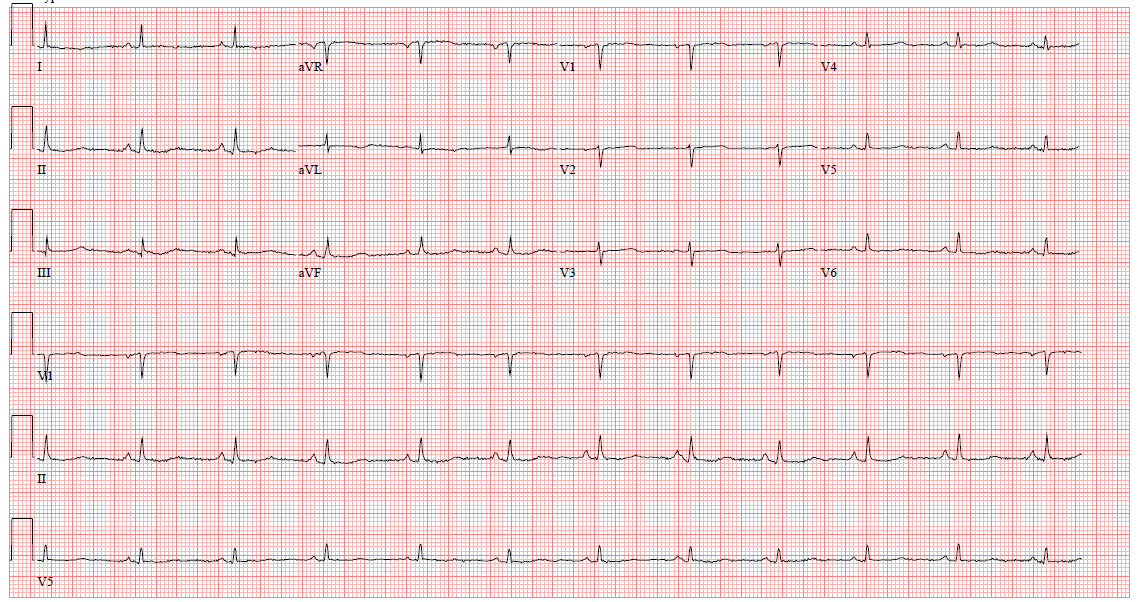

Figure 1

Electrocardiogram showing low QRS voltage.

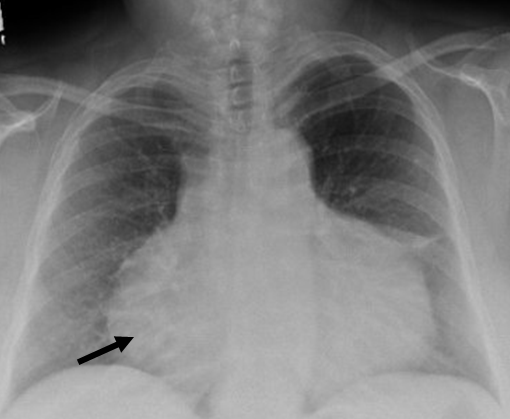

Figure 2

Chest X ray showing "water bottle sign" (black arrow) suggestive of a large pericardial effusion.

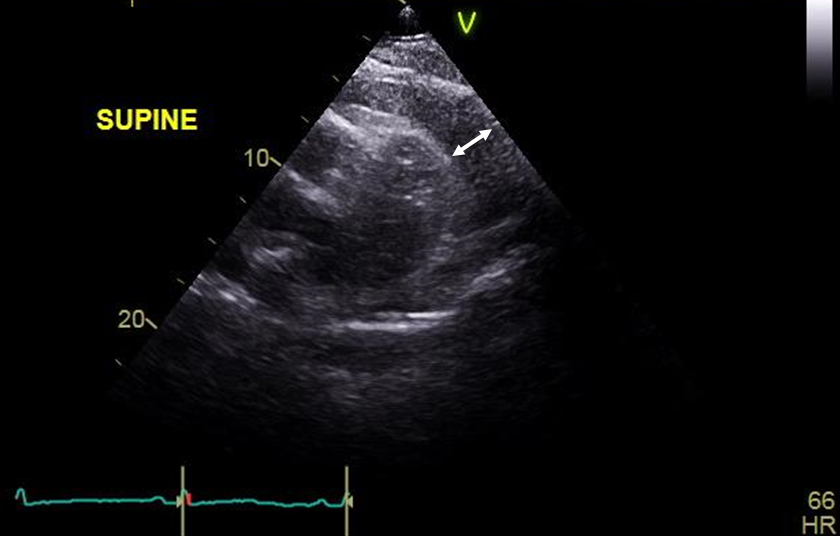

Figure 3

Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal short axis view, showing a large anterior pericardial effusion measuring 2.5 cm (white arrow).

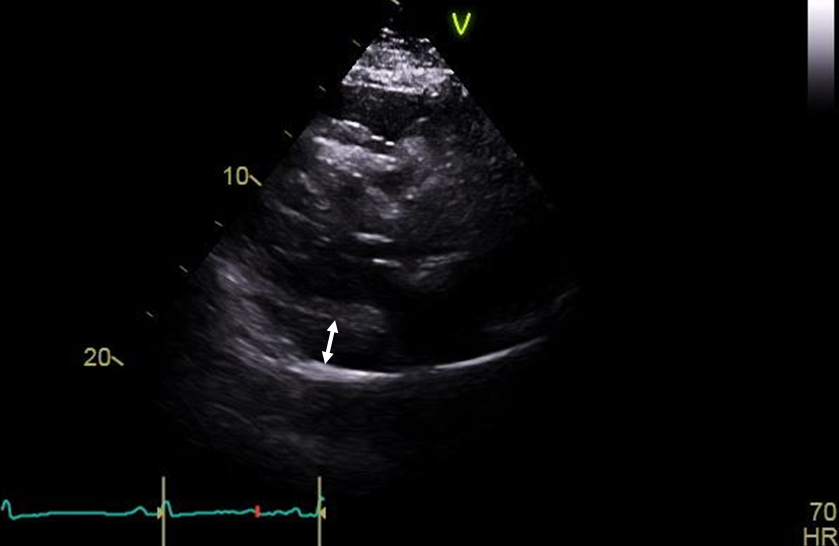

Figure 4

Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal short axis view, showing a posterior pericardial effusion measuring 1.3 cm (white arrow).

The correct answer is: B. This patient has a pericardial effusion secondary to an underlying known disease, therefore pericardiocentesis can be deferred and the underlying condition should be treated.

This patient has a large pericardial effusion secondary to untreated severe hypothyroidism which was found incidentally during pre-operative evaluation for hip replacement. In the presence of suggestive features in the history, physical exam, electrocardiogram or chest X ray, an echocardiogram is indicated to diagnose and assess the physiologic consequences of the pericardial effusion.1 The patient has a large (free-space on echocardiogram > 20 mm)2 asymptomatic pericardial effusion due to severe hypothyroidism (diagnosed by a TSH of 104 uU/mL and a free thyroxine of 0.2 ng/dL ). She has no history of malignancy, no evidence of pericarditis (absence of chest pain, suggestive EKG features, pericardial rub or markedly elevated inflammatory markers) or signs of tamponade clinically (absence of hypotension, jugular venous distention, pulsus paradoxus, shortness of breath or tachycardia) or echocardiographically (absence of diastolic collapse, excessive respiratory variation of mitral and tricuspid valves). The patient is also not immunosuppressed and does not have any signs or symptoms concerning for tuberculosis. Although the pericardial effusion is large, our patient is asymptomatic as there has been an insidious buildup of fluid over a long period of time.3

In the absence of features suggestive of tamponade, bacterial infection or malignancy, the next step is to check inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate).4 If elevated or if pericarditis is diagnosed, treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine is indicated. Otherwise, a search for an alternative underlying cause of the effusion must be performed. Differential diagnosis includes heart failure, myocardial infarction, iatrogenic secondary to cardiac procedures, trauma, advanced renal failure, autoimmune diseases and hypothyroidism.2,5 If one of the above is present, treatment should be directed toward the underlying disease process rather than pericardial drainage.4

Hypothyroidism is well known to cause pericardial effusions in 3 to 30% of cases,4,6 and is mostly present in severe hypothyroidism and thus more prevalent with lower thyroxine levels.6,7 However, it is only responsible for 2 to 10% of pericardial effusions.2,8,9 The mechanism by which hypothyroidism causes pericardial effusions is complex and thought to be a mixture of pulmonary hypertension and intravascular leak into the pericardial space due to a drop in the plasma oncotic pressure induced by the hypothyroid state.7

Although the 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend TSH testing in chronic pericardial effusions only,4 a study by Levy et al. recommends systematically measuring TSH in all patients with pericardial effusion.8 In this study, 14 out of 141 patients previously diagnosed with idiopathic pericarditis were found to have pericarditis secondary to hypothyroidism. This is particularly important since pericardial effusions in this case can be easily treated with thyroid replacement therapy. The recommended initial levothyroxine dose is generally 1.6 μg/kg daily, but it can vary depending on the patient's age and comorbidities.10

Based on the 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases, pericardial drainage for pericardial effusion is indicated in the following situations (Class I recommendation, level of evidence B):4

- Symptoms occurring despite medical treatment for an underlying disease.

- Clinical or echocardiographic evidence of tamponade.

- Evidence of widespread malignancy.

- Suspected bacterial pericarditis (tuberculous or purulent)

- Chronic pericardial effusion (i.e., effusion persisting more than 3 months), since (a) large effusions without a clear cause are most likely chronic idiopathic pericardial effusion;2 (b) diagnostic or therapeutic pericardiocentesis does not affect outcome in the first 3 months;11 and (c) after 3 months, the risk of sudden decompensation into tamponade becomes significant.11,12

An additional criterion to consider would be if there is rapid accumulation of pericardial fluid in less than a month because of increased risk of tamponade.3 Effusions accumulating fast might become physiologically significant earlier and up to 30% of large chronic pericardial effusions (>20mm) without tamponade may ultimately progress to tamponade, so planning for elective drainage is appropriate.4,12

Once there is evidence of cardiac tamponade or if pericardiocentesis is planned, the 2014 European Society of Cardiology position statement recommends a scoring system to triage patients,13 with points given depending on the etiology of the tamponade, clinical presentation and imaging studies. Pericardiocentesis can be deferred for up to 48 hours if the score is less than 6 in the absence of surgical indications for drainage or hemodynamic instability.14

Therefore, the next step in management of this patient would be to treat the underlying severe hypothyroidism and consider pericardiocentesis only if there is interval development of symptoms despite treatment, tamponade or if the effusion persists for more than 3 months. Obviously, every procedure has its complications and pericardiocentesis is not an exception. With a risk of complications between 4 and 20%,15 pericardiocentesis must not be done routinely unless truly indicated and performed by an experienced provider. Complications include laceration of the ventricles (rate of 0.7 to 2% and in up to 15% without the use of echocardiography),16-19 pneumothorax (rate of 1.1 to 2%),17,18 acute pulmonary edema (rate of 1.2%),20 arrhythmias (rate of less than 1%)17,18,20 and death (rate of 0.1 to 0.3%).16,17

As for the approach to pericardial drainage, pericardiocentesis is generally recommended for most cases with surgical intervention being reserved for malignant and purulent pericarditis, effusions not safely accessible percutaneously, and for recurrent pericardial effusions despite two prior pericardiocentesis.5

References

- Klein AL, Abbara S, Agler DA, et al. American Society of Echocardiography clinical recommendations for multimodality cardiovascular imaging of patients with pericardial disease: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26:965-1012.

- Sagrista-Sauleda J, Merce J, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Clinical clues to the causes of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med 2000;109:95-101.

- Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation 2006;113:1622-32.

- Adlery Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the task force for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2015;36:2921-64.

- Sagrista-Sauleda J, Merce AS, Soler-Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial effusion. World J Cardiol 2011;3:135-43.

- Kabadi UM, Kumar SP. Pericardial effusion in primary hypothyroidism. Am Heart J 1990;120:1393-5.

- Yamanaka S, Kumon Y, Matsumura Y, Kamioka M, Takeuchi H, Sugiura T. Link between pericardial effusion and attenuation of QRS voltage in patients with hypothyroidism. Cardiology 2010;116:32-6.

- Levy PY, Corey R, Berger P, et al. Etiologic diagnosis of 204 pericardial effusions. Medicine 2003;82:385-91.

- Ma W, Liu J, Zeng Y, et al. Causes of moderate to large pericardial effusion requiring pericardiocentesis in 140 Han Chinese patients. Herz 2012;37:183-7.

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract 2012;18:988-1028.

- Merce J, Sagrista-Sauleda J, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Should pericardial drainage be performed routiney in patients who have a large pericardial effusion without tamponade? Am J Med 1998;105:106-9.

- Sagrista-Sauleda J, Angel J, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic chronic pericardial effusion. N Engl J Med 1999;34:2054-9.

- Arguilian E, Halpern DG, Aziz EF, Uretsky S, Chaudhry F, Herzog E. Novel "CHASER" pathway for the management of pericardial disease. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2011;10:57-63.

- Ristic AD, Imazio M, Adler Y, et al. Triage strategy for urgent management of cardiac tamponade: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2279-84.

- Kumar R, Sinha A, Lin MJ, et al. Complications of pericardiocentesis: a clinical synopsis. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2015;5:206-12.

- Cho BC, Kang SM, Kim DH, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of pericardial effusion in patients who underwent echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis: Yonsei Cardiovascular Center experience, 1993-2003. Yonsei Med J 2004;45:462-8.

- Tsang TS, Enriquez-Sarano M, Freeman WK, et al. Consecutive 1127 therapeutic echocardiographically guided pericardiocenteses: clinical profile, practice patterns, and outcomes spanning 21 years. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77:429-36.

- Tsang TS, Freeman WK, Barnes ME, Reeder GS, Packer DL, Seward JB. Rescue echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis for cardiac perforation complicating catheter-based procedures. The Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:1345-50.

- Bishop LH, Estes EH, McIntosh HD. The electrocardiogram as a safeguard in pericardiocentesis. J Am Med Assoc 1956;162:264-5.

- Maggiolini S, Gentile G, Farina A, et al. Safety, efficacy, and complications of pericardiocentesis by real-time echo-monitored procedure. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:1369-74.